Read more on

|

Tweet

|

– Anonymous

Being autistic means being different – not only different from those outside the autistic spectrum but also from those inside. It might be said that autism is ultimate individuality.

This, of course, leads to problems in a society where everybody is expected to comply and conform since being on the individual end of the neurological spectrum provides us with both an intellectual advantage and a societal disadvantage. When as children we are pressured into suppressing our individual identities by being compelled to do things that make us uncomfortable and to perform routines and rituals without seeing the reason behind them, we start to revolt against a world that doesn’t make sense to us and tries to force us into submission.

When this proves unsuccessful, we withdraw from the world as much as possible in order to protect our feelings and our identity. And if you want to get through to us, the most important thing is understanding our position – empathy, respect, reassurance and patience will get you a lot further than you imagine.

While mainstream children manage to learn by rote, copying adults and following instructions, we learn by experimenting, enquiring and logical thinking. Therefore it’s not sufficient to tell us what to do and what not to do, you will have to convince us of the reasons behind it; this is also why we are far more likely to question anything without (or with flawed) proof or things that are handed down as facts.

Figuring things out rather than copying adults can sometimes take a bit longer, such as tying our laces or riding a bike, but the acquired skills will be all the more ingrained.

Another significant difference in the way we learn is that either we understand something that is taught or we don’t. If we don’t, teaching it over and over in the same manner will not make the subject more accessible to us; you will have to look for alternative methods to do so. And if we understand it, there is no need for permanent repetition of the subject matter; on the contrary, rote learning and repetition will dull our senses and reduce our attentiveness by neglecting our constant need for intellectual stimulation. This is also the cause of our reluctance to do homework.

Furthermore, autistic children (and adults) usually learn more effectively through intrinsic motivation (such as curiosity or personal aims) whereas mainstream ones are more easily manipulated by external motivators (such as praise, rewards or pressure).

The counterproductive effect that external motivators have on all children, not just autistic ones, has been pointed out by many educators, such as Alfie Kohn in his book Punished by Rewards.

Many parents of autistic children complain about their frequent why questions and wrongly assume that they merely want to annoy them. We do want to know why things are done a certain way, why things are the way they are etc. Answering these questions with 'Because it was always done like that' or 'Because I say so' are not only unsatisfactory but also condescending and will be registered as such.

Because of our ability to focus on matters of interest and locate information, and because of our difficulties with traditional teaching methods, many of us become autodidacts who effectively teach themselves in their preferred areas.

It is also important to give us the feeling that we have a say in our lives. Giving us plenty of choices will make life a lot easier, both for you and for ourselves.

Negotiations are another recommendable tool to empower us. Rather than giving us orders and expecting us to follow them, you could express your expectations, listen to our point of view and come to a mutual agreement with us. This not only gives us the feeling to be respected as an individual person, it also prepares us for our adult lives when we are supposed to be able to stand up for ourselves.

We are far more likely to be helpful than we are to be docile. Therefore a request is more likely to have the desired effect than a demand; asking, ‘I’m busy with the laundry, would you mind doing the dishes?’ has more chance of success than just saying, ‘Do the dishes!’

Stress-causing factors like the unpredictability of our environments and others’ attempts to pressure us into acting less autistically (especially the use of behavioural therapies against us) often lead to chronic gastrointestinal problems such as constipation or diarrhoea as well as psychological disorders such as PTSD or OCD.

We find it difficult to switch tasks and activities without having the time to prepare for the change. Therefore it is extremely helpful (and advisable) to give us sufficient notice beforehand, such as ‘You'll have to be ready for school in half an hour’ or ‘Dinner will be ready in ten minutes’.

Because we are never sure what to expect from those around us and society in general, and because our efforts to communicate are routinely overlooked, misunderstood or ridiculed, most of us live in a permanent state of anxiety and frustration.

Due to our individual identities (as opposed to the collective identities of others) we are far more rational and far less biased than others and tend to be immune and even oblivious to group dynamics. As members of a group we still retain our individuality (rather than seeing ourselves as group members) and are therefore unlikely to be swerved by majority opinions, peer pressure and authority figures.

Because of this most of us are also more efficient working on our own than in a group setting and less willing to compromise on matters that are important to us.

Our individual identities are also the reason why most of us are uninterested in fashion. We don’t try to impress with our appearance but with our intellect.

While we are easily deceived by others because we take everything at face value, it is more difficult to manipulate us: either our lack of social awareness leaves us oblivious to the attempt, or we see right through it which only strengthens our resolve.

In order to avoid ostracisation and repercussions, many autistic people (subconsciously or consciously) temporarily suppress their individual identities and try to take on the collective identities of their surroundings by copying the behaviours and opinions of others, especially in formal (and therefore extremely stressful) environments like school, workplace and church. This coping mechanism (which is practically self-prescribed ABA) is known as masking, and pretending to be someone we are not is quite exhausting and mentally and even physically draining; therefore many of us need to let off steam as soon as we return to a safe(r) environment while others may need sufficient time to ourselves to recuperate. Long-term masking can also lead to autistic burnout.

More than other individuals, autistic people need privacy and time on their own. Because all kinds of socialising, even (and in many cases especially) with family members, are demanding and exhausting for us, we need to spend a lot of time away from it all to avoid sensory overload. Therefore autistic children who have no opportunity to retreat to a safe place where they can be on their own tend to develop more mental problems and difficult behaviours and often end up on the ‘lower-functioning’ end of the spectrum.

While communication between autistic and mainstream people is prone to misunderstandings, communication between autistic people is just as effective as it is between mainstream people. (You could compare it to two different operating systems.) Therefore autistic children benefit from the company of other autistic children as well as that of autistic adults as role models.

Despite our headstrongness we are easily pushed into uncomfortable and even embarrassing situations within personal and professional relationships. This is a result of either our fear of jeopardising this relationship in case we don’t oblige or of our ignorance as to how much can be reasonably expected from somebody within such a relationship. For example, the exploitation of contacts in order to gain an advantage for ourselves or somebody else, i.e. the ‘old boy network’, goes against every fibre of our beings, and being talked into doing so by a partner, relative, friend or boss leaves us in a state of mental purgatory.

We tend to have a very strong and inflexible sense of morality and justice which others often consider stubborn. As in all areas, we develop our sense of right and wrong by rational thinking, such as 'I don’t want to be hurt, therefore it is wrong for anybody to hurt anybody else' (you could call it logical empathy). This makes our opinions more rigid and allows for fewer exceptions; it also makes us more likely to disobey orders that go against our conscience and speak up against any form of injustice that is accepted by society, regardless of the consequences. We also tend to be incorruptible.

Most of us are firmly grounded in the present because the past can’t be changed and the future can’t be known.

Sometimes we find it difficult to seek help or assistance for fear of annoying others or being considered ignorant.

It is quite common for us to develop unique approaches to anything from doing chores to solving problems. You may feel the need to correct us because our techniques seem too awkward, unconventional or unnecessarily complicated, but keep in mind that what appears complicated to you may be simple for us, and vice versa. Just tell yourself, ‘If it works, don’t fix it.’

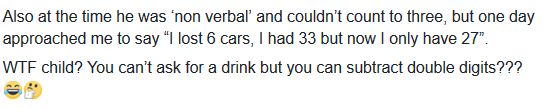

Many of us have problems articulating ourselves, and some of us never talk at all. This doesn’t mean that we don’t want to communicate; many of us have learned to express ourselves through writing or typing on computers or stencil letter boards or by learning sign language and thus were able to finally get in contact with our caregivers and the world. It also gave us the opportunity to prove that we are not as stupid as many like to believe – on the contrary, most of us turn out to be highly intelligent.

Some of us approach language by using echolalia since they associate full sentences with certain scenarios before learning the meanings of individual words. In this case it is helpful to phrase sentences from the child’s perspective and follow their lead.

Autism is a neurological orientation, and therefore the term ‘high-functioning autism’ makes as much sense as the term ‘high-functioning left-handedness’. Besides this, the labels ‘high-functioning’ and ‘low-functioning autism’ are both misleading and demeaning. The ‘high-functioning’ label dismisses our struggles, anxieties and frustrations in trying to adapt to a strange society and its rules while the ‘low-functioning’ label dismisses entirely the enormous potential of every autistic individual - and what you don’t look for, you won’t find. It is no surprise that the ‘severity’ of autism, i.e. the difference between ‘low- and high-functioning autism’, has been linked to the experienced stress levels in recent studies which indicates that the more we are put under pressure, the ‘lower-functioning’ we become. Furthermore, would you label a 3-year-old who doesn’t speak but solves a Rubik’s Cube in two minutes as high- or as low-functioning?

A lot of us find it difficult to talk about the weather (unless meteorology happens to be our area of expertise, in which case you may be sorry you brought it up) because we don’t see the point, and communication for the sake of communication is an alien concept to us. We also find it difficult if not impossible to say niceties that we don’t mean; if we did, not only would our compliments be entirely worthless, but we would put our credibility at stake.

Most of us have one or more areas of expertise from a very young age which we may rant on about, either because we assume that you’re interested or because we can’t think of a more appropriate conversation topic.

We say what we mean with no intention of offending anyone, but our honesty and bluntness are often misinterpreted.

We tend to have a very strong sense of fairness which generally isn’t affected by our association with either side.

We have a hard time noticing and deciphering non-verbal communication, such as body language, facial expressions and undertones. So if you have something to say, say it – literally.

Many of us have problems making eye contact because it feels intimidating and prevents us from focussing on the conversation.

Most of us have some sort of a stim (which is short for self-stimulation) such as rocking, hand flapping or face picking; basically, it's a more obvious form of fidgeting. There can be plenty of reasons for this since it helps with self-reassurance, focussing and dealing with anxiety, to name but a few.

We can only do one thing at a time, but we are a lot more focussed on and absorbed in matters that are of interest to us than others are. We have great potential, provided we are given the opportunity to develop it.

Perfectionism is another common trait in autism. Many of us have to do everything 100% and get highly embarrassed when we (or others) discover the tiniest flaw in our work. I’ve come to think that the fear of not being able to master something perfectly from the beginning may be a common reason for not even attempting it (such as speech) until we consider ourselves competent.

Sometimes autistic children take more time to process information because they process more information. For example, when shown a painting of a flower stall in a street and asked how many flowers they see, a mainstream child is likely to count the flowers in the stall and come up with a quick answer while an autistic child is more likely to scan the entire picture for flowers in other possible places like behind windows or on women's hats.

Some autistic children are accused of having no sense of others' bodily autonomy. However, many of these children are forced to hug people they don't want to hug, being picked up without consent or even exposed to corporal punishments, giving them the impression that there is no such thing as bodily autonomy. (The same applies to other concepts, such as privacy and respect.)

Sometimes, when asked what happened right in front of their faces a moment ago, an autistic child may say they don't remember. This is often considered a lie and may be interpreted as a sign of a guilty conscience. It usually is not.

When people witness something happening unexpectedly or quickly, or when they are distracted, they generally can't recall the details correctly. In order to avoid embarrassment, the subconscious of most people fills in the gaps and creates a false memory that makes sense of the situation and, if applicable, presents them in a favourable light.

Most autistic people, due to our rational disposition, lack this mechanism and will truthfully state that they don't remember.

While some autistic children prefer to stay to themselves, many try to socialise but end up being ostracised and subsequently accused of not playing with others.

Due to our individual identities, autistic play can be quite different from the play of other children and is therefore pathologised by many professionals.

According to Wikipedia (who, according to their citation, took the definition from Catherine Garvey’s book Play) ‘play is a range of intrinsically motivated activities done for recreational pleasure and enjoyment’. It follows that there is no way of playing incorrectly, and yet this is what many autistic children are accused of. Dismissing their way of playing and coercing them into what others consider 'appropriate play' causes them stress and anxiety and therefore contradicts the definition of play.

While professionals routinely insist on what they call ‘functional play’, i.e. playing with a toy in the way its designer intended, autistic children may be more interested in how the toy functions.

This is an inexhaustive list of a few forms of play autistic children may engage in, some of which are not usually associated with play but which fit the definition as well:

Structural Play: Lining up toys, stacking them or sorting them by certain criteria. This may be done in order to hone their counting or organising skills, to create patterns that often go unnoticed by others, or as a form of art.

Analytical Play: Figuring out how things work - for example, by repeatedly watching a wheel spin to study the mechanics.

Experimental Play: Conducting experiments to study the relationship between things, such as dropping different objects to the ground from different heights to study the differences in their impact.

Autodidactic Play: Teaching themselves new skills or researching matters of interest.

Creative Learning: Using acquired information in creative ways by including it in their play and improvising rather than merely repeating it.

(I dare say that the vast majority of scientists, inventors, technicians and engineers engaged in structural, analytical, experimental and autodidactic play and creative learning when they were children.)

Sensory Play: Enjoying activities that stimulate their sense of touch, smell, taste, sight and/or hearing as well as those involving movement and balance.

Parallel Play: Enjoying the company of others while doing their own thing. The autistic child’s way of playing, such as analytical or experimental play, wouldn’t be understood by others, and their participation could seriously disrupt their play and their thought process, or they could alter a prepared script the autistic child is playing out.

Electronic Devices: Learning, researching, connecting and playing on electronic devices. Many parents of autistic children have limited their children’s time on these devices, leading to distress, frustration and anxiety. Parents who removed screen time limits for their autistic children reported that their children thrived and became more balanced, and that children with speech delays rapidly improved their verbal skills.

Observation: Intensely observing things of interest to them, often those that appear mundane to others. Observation helps to understand and relate to their environment.

Reflection: Thinking about all kinds of things. It may look like the child is daydreaming, staring into space or simply lazy. They aren’t. The autistic mind is always busy.

(Regarding thinking, we also tend to link information or observations that appear unrelated or concern different areas and come up with unique ideas or theories. You could think of it as connecting the dots on different sheets.)

(Read more on Autistic Play.)

Even though we tend to excel in our chosen professions, 85% of autistic people are unemployed because of our perceived social shortcomings and our difficulty to sell ourselves ('The list of things you are not supposed to do in an interview is practically a definition of autism.' - Steve Silberman), and the remaining ones usually work in menial jobs regardless of their qualifications. And when we get the job, we are unlikely to live up to our colleagues’ and employers’ social expectations.

Many of us have sleeping problems because we find it difficult to stop thinking and ‘switch our brains off’.

We are easily discouraged. One 'He won’t ever learn to spell' can be the death knell of a brilliant literary career.

A researcher observed that 'if you drop your expectation level for a child with autism, they will drop to that level.'

THIS FACT CAN’T POSSIBLY BE OVERESTIMATED!

We also have a tendency to seek reassurance from others in our fields of expertise. The problem can arise that we know more about the subject, even as children, than the adults around us, and therefore don’t get a qualified answer or appropriate reaction. If we seek reassurance and you don’t have the knowledge to supply it, please be honest and tell us exactly that.

Due to our reduced habituation we perceive all sensations unfiltered, which means the buzzing sound of the fridge and the sizzling of the frying pan are just as intense for us as your voice when you’re talking to us. Sometimes the intensity of these sensations can become too much for us to deal with and lead to a meltdown which may look like, but should not be confused with, a tantrum. Others may react to such overwhelmment with headaches or migraines, epileptic fits or absence seizures or a state of hyperactivity. In many cases these reactions either become avoidable when we reach the stage of being in control of our own lives or are replaced with an obsessive but tolerated coping mechanism in adulthood.

The sensations triggering us off can be of any kind, such as visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, gustatory or emotional.

It has been observed that we generally don’t express our emotions and our experience of pain as openly as others, and that it can be difficult for others to know how we feel. The reason for this possibly lies once again in our different natures: mainstream people tend to share their feelings due to their social nature while we tend to keep our feelings private due to our individual nature, and being pressured into expressing and sharing them can cause our anxiety to go through the roof and lead to serious meltdowns.

The same is true about empathy: while we do empathise with others, often to a painfully intense degree, it rarely shows on our faces.

Autistic individuals often display attitudes and behaviours that are considered extreme, and in many cases these are caused by insecurity. For instance, our environment is governed by rules that in many cases can be bent. Since we are not aware of the acceptable extent of diversion from them, we tend to either become sticklers for these rules and won’t tolerate any exceptions, or we rebel against rules that don’t make sense to us altogether (which comes more naturally to us). And while some of us cave in under pressure to give up our identities (at the cost of their mental health and intellectual potential), others fight tooth and nail to hold on to theirs.

Other examples would be autistics who, because they don’t know how to regulate eye contact, either avoid it entirely or stare at the other person, or those who, unaware of the rules of conversation, either remain quiet or keep waffling to an uninterested audience.

Many mainstream but often well-meaning professionals consider themselves experts on autism. Since autism is ultimate individuality, and every individual’s autism manifests itself in different ways, there are no experts on autism; the only ones with a basic understanding are other autistic people. Therefore, never take an 'expert’s' word on what we can and, more importantly, what we cannot do. Never believe there is anything we can’t achieve!

When a child is diagnosed with autism, many ‘experts’ will try to sell you all kinds of therapies to mainstream your child. In most cases all the child needs is to be accepted and appreciated for who they are. Nobody needs therapy (or medication, for that matter) just because they are autistic.

If the child needs support in certain areas, such as speech or motor skills, get them that support.

The most pushed therapies against autistic children are behavioural conversion therapies such as ABA which only target the behaviour and ignore the reasons for the behaviour, thus leading to long-term psychological damage such as PTSD.

If a behaviour is problematic, try to find out the cause(s) and work with the child instead of against them. A great guide is Dr Ross Greene’s book The Explosive Child (you can find a summary here).

When explaining their neurological orientation to an autistic child, pointing out the intellectual advantages is just as important as mentioning the social disadvantages. Tell them it's all right to think differently from others, it's all right not to go along with everything others are doing, saying or wearing and it's all right to do their own thing, even if they're ostracised and bullied because of it. Let them know that it's never the ones who go with the crowd who change the world for the better or have original ideas. Assure them they don't have to do things they're uncomfortable with or that make others uncomfortable, that it's perfectly fine to ask why questions and that they have the right to remain themselves, no matter what others say.

Also, feel free to show them my Affectionate Letter to All Autistic Children to understand their neurological orientation.

Last but not least, humans in general tend to be biased and irrational. Autistic people are the notable exception, and being unbiased and rational in a biased and irrational world can be very confusing and creates most of the problems we have to face.

Autism is an integral part of our identities, just like gender and ethnicity. And just like nobody talks of ‘persons with femaleness’ or ‘persons with Caucasianness’, we are not ‘persons with autism’; the vast majority of us (88.6%, according to this survey) prefer identity-first language (i.e. ‘autistic person’), and we generally can distinguish those who support us from those who patronise us by their choice of either respecting or ignoring this preference.

For most of us, being ourselves is more important than fitting in, but we all are walking a tightrope between our desires to be our authentic selves and to be accepted.

Most of us embrace our neurological orientation and see it as a natural and indispensable part of human diversity. Understanding and respecting our individuality and uniqueness will make it much easier for us to function in a world that doesn’t make a lot of sense to us.

There are leaders, and there are followers. But there are also those who don’t want to be followed or led, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

(By the way, many of these recommendations work for mainstream children as well. You'll be surprised!)

Fun Fact: Autism was first pathologised in Nazi-occupied Austria and the United States in the early 1940s, in countries and at a time that saw the ruthless enforcement of conformity and compliance and the perception of individual expression as an act of treason or a sign of mental illness.