Read more on

|

Tweet

|

Since I was a child I have been amazed at how easily people are manipulated and follow a crowd, a leader or a trend. When I realised I was autistic and subsequently got diagnosed at the age of 50, I noticed that this gullibility is the default setting for mainstream persons, a result of their urge to fit in.

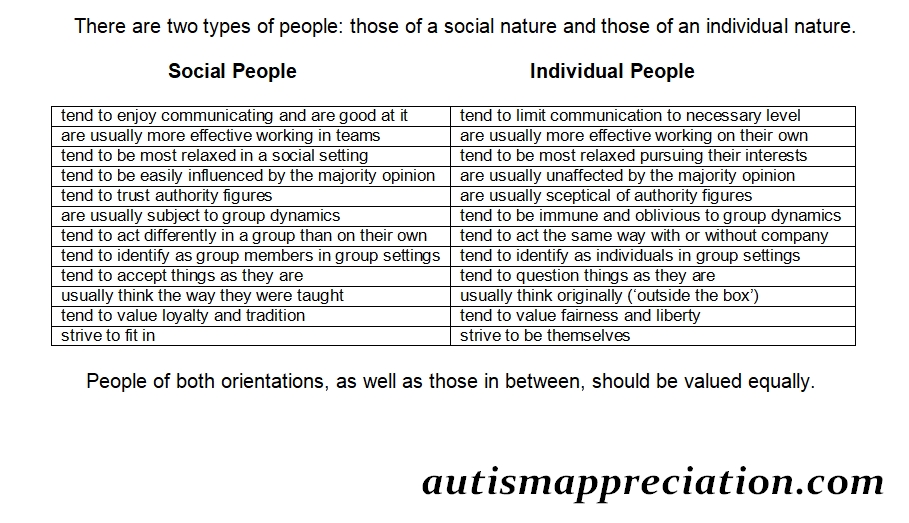

The individual nature of autistic people stands in stark contrast to the social nature of mainstream people.

In a group setting, or in the presence of an authority figure, the behaviour of mainstream people differs from their usual behaviour; the behaviour of autistic people does not. In some cases the autistic individual may not even be aware of the existence of a group.

If the group majority or a person in authority perceive things a certain way, mainstream members have a strong tendency to agree with them regardless of the reality. On autistic group members, however, their suggestions have no effect, just like they are less likely to fall for illusions or other cognitive biases such as the bandwagon or the framing effect. A study in 2020 also found that we tend to be incorruptible (which the researchers consider a social deficit).

In a group setting, just as in any other situation, autistic persons tend to take statements and people at face value and remain oblivious to any hidden agendas and underlying conflicts.

For a while I served on the board of a primary school. I was task-orientated and, according to the others, did an excellent job. However, I was entirely unaware of a power struggle that was going on around me until the situation exploded.

Even as members of a group the personality of autistic people remains unchanged; this is the reason why we tend to be immune to peer pressure, groupthink (avoidance of conflict), groupshift (taking a more extreme position than we would outside the group) and bias towards them (outsiders). We also see no point in reputation maintenance and rather focus on the task at hand (where applicable).

And because we never hide behind a group identity or an authority, I believe that autistic individuals are far more likely to accept responsibility for their own actions.

While mainstream persons tend to work more efficiently in groups, autistic persons are more efficient working on their own; we have very concrete ideas and therefore loathe compromises. For example, the Sistine Chapel ceiling was painted by Michelangelo; can you imagine him as a part of a team with limited input and having to negotiate every character and cloud he painted?

Human rights movements usually begin as protests organised by a group, but some are sparked off by the actions of individuals. Autistic people, because of our individual nature (and because we tend not to be listened to) are more likely to choose this course of action. One example is Greta Thunberg, the climate activist who started a mass movement with a solitary protest outside the Swedish parliament: ‘People also say that since I have Asperger I couldn’t possibly have put myself in this position. But that’s exactly why I did this. Because if I would have been ”normal” and social I would have organized myself in an organisation, or started an organisation by myself. But since I am not that good at socializing I did this instead.’

On the downside, the fact that we are one of the last unheard minorities may be due to our preference for individual work which makes it difficult to organise a mass movement. Thunberg was successful because her agenda hit a nerve with the masses; our cause doesn’t.

The human inclination for conformity and compliance with authorities has long been underestimated. Inspired by the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann who claimed to have ‘just followed orders’, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted the Milgram Experiment in which subjects were asked to run a test with a volunteer in an adjacent room and to deliver an electric shock of increasing voltage for every wrong answer. From a certain point the volunteers screamed and later begged the subjects to stop. Some subjects voiced concerns, but the experimenter told them that the experiment had to be concluded.

Milgram had polled his colleagues beforehand, and the highest estimate was that 3% of all subjects would continue to the potentially fatal 450V shock. 65% did.

The subjects justified their behaviour by claiming that they had ‘just followed orders’.

The experiment has since been repeated frequently with consistent results, proving that two thirds of all humans are herd animals who unquestioningly obey authority and follow the crowd.

Autistic people don’t ‘just follow orders’. We are sceptical if not resentful of authority figures and generally disobey any order that goes against our conscience or doesn’t make sense to us. It certainly would be interesting to see the experiment repeated with autistic subjects; I dare say that not a single one will go all the way.

Mainstream people usually follow the set of worldviews of a political camp to which they conform in their entirety and from which they hardly derive (you could call it an opinion package) while autistic persons form their own opinions on individual issues. Unfortunately there are no studies, but you will find that many autistic people hold views others may consider incompatible. One example is the pro-life liberal movement, which continued in the 1960s when the mainstream liberal and feminist position shifted from pro-life to pro-choice, by liberals who consider the right to life the most basic human right. With less than 2% of the general population having an autism diagnosis, and doubling that number to account for the self-diagnosed, you’d statistically expect less than 4% of autistic people in any given group; a poll on Pro-Life Liberal’s FB page revealed that 44% of respondents identify as autistic. (I’m not saying that autistic people are generally pro-life liberals, my point is that we are less likely to subscribe to opinion packages.)

Being different ourselves, autistic people also tend to be more accepting of diversity. Another reason for us being, on average, more tolerant than others again lies in the social nature of mainstream people who tend to identify with groups rather than as individuals. These groups, such as nationality, race or religion, tend to foster an us-v-them mentality that views outsiders and other groups with suspicion and animosity. In many cases the group identity is used to instil an irrational fear and hatred of other groups who, in fact, don’t pose any threat. Because of our individual nature autistic people are less likely to judge people by their group affiliation.

Our perceived stubbornness, inflexibility and wariness of authority figures, combined with our increased sense of fairness and justice, provide the ideal material for human rights activists who permanently strive to change the world for the better; besides Greta Thunberg and Julian Assange there are Mahatma Gandhi whose autobiography clearly demonstrates that he was autistic and Nelson Mandela who is also suspected of having been autistic.

While the focus of this article is on the contribution of autistic people to the moral advancement of mankind by not giving in to group dynamics and blindly following authorities, the necessity of autism in science and the arts, due to our power of original thought (amongst other advantages such as focus and attention to detail), has already been pointed out in the 1940s by Hans Asperger: ‘It seems that for success in science or art a dash of autism is essential. For success the necessary ingredients may be an ability to turn away from the everyday world, from the simple practical, an ability to rethink a subject with originality so as to create in new untrodden ways, with all abilities canalised into the one speciality.’

The likely connection between autism and Neanderthal DNA has been suggested as early as 2001. While Homo sapiens had made no significant progress in 150,000 years, the Neanderthals painted their caves, played musical instruments, developed advanced tools and complicated manufacturing and hunting techniques and buried their dead. Only after Homo sapiens had assimilated the Neanderthal, the Great Leap Forward occurred which eventually gave rise to modern humans.

There are voices calling for our elimination. So what would the world look like without us?

‘You would have a bunch of people standing around in a cave, chatting and socializing and not getting anything done.’ - Temple Grandin

In order to validate (or invalidate) the claims I make it would be interesting to see the following studies and experiments conducted:

1. The Milgram Experiment carried out on persons with an autism diagnosis. (It should also be recorded whether they were subjected to ABA in the past; if, against my prognosis, any autistic person would be ready to send 450V through somebody else, they are most likely to have experienced conditioning in childhood.)

2. A case-control study on the combination of political views regarding their deviation from the combination of mainstream positions.

3. A case-control study on the willingness of subjects to accept responsibility for their own actions in a group setting.

This article was a milestone in developing the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis three years later in which I argue that autism is a social construct for those who resist social conditioning. Abstract: 'All children are born with individual identities, but almost all of them undergo social conditioning and are forced to take on collective identities instead. Human progress is driven by people who resist social conditioning (or are not subjected to it in the first place) and retain their individual identities at the cost of being ostracised and pathologised while those who identify collectively provide the network to spread it.'

MORE ON AUTISM