Read more on

|

Tweet

|

In this article I highlight six areas that clearly demonstrate the level of bias against autism.

Areas of Expertise

Nobody would say that Einstein was obsessed with physics or that music was Beethoven’s special interest. However, if they were children in today’s world, this is exactly what would happen.

Early Reading Skills

There have always been children who learned to read at an earlier age than others, and some of them are astonishingly young. Until recently their parents tended to be proud of them and show off their smart offspring.

Stimming

When Karen is excited she throws her hands up in the air. When she is nervous she chews on her pen. When she is concentrating she taps her fingers. All of this is perfectly all right because Karen is not autistic.

Immunity to Group Dynamics

Many human rights activists are revered for their abilities to withstand group dynamics and peer pressure and to defy laws and orders they consider unjust, standing up for their convictions instead of remaining silent and going along with the crowd or following commands. These are hallmark traits of autistic people in whom they are considered social shortcomings.

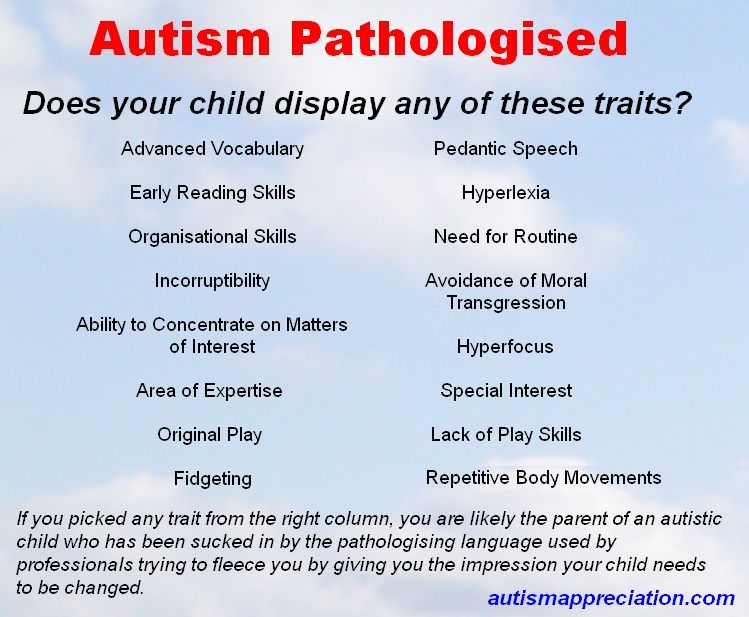

Incorruptibility

A study in 2020 showed that autistic children tend to be incorruptible, concluding that autistic children ‘were much more likely to reject the opportunity to earn ill-gotten money by supporting a bad cause’ than others, which the researchers consider a deficit called ‘avoidance of moral transgression’.

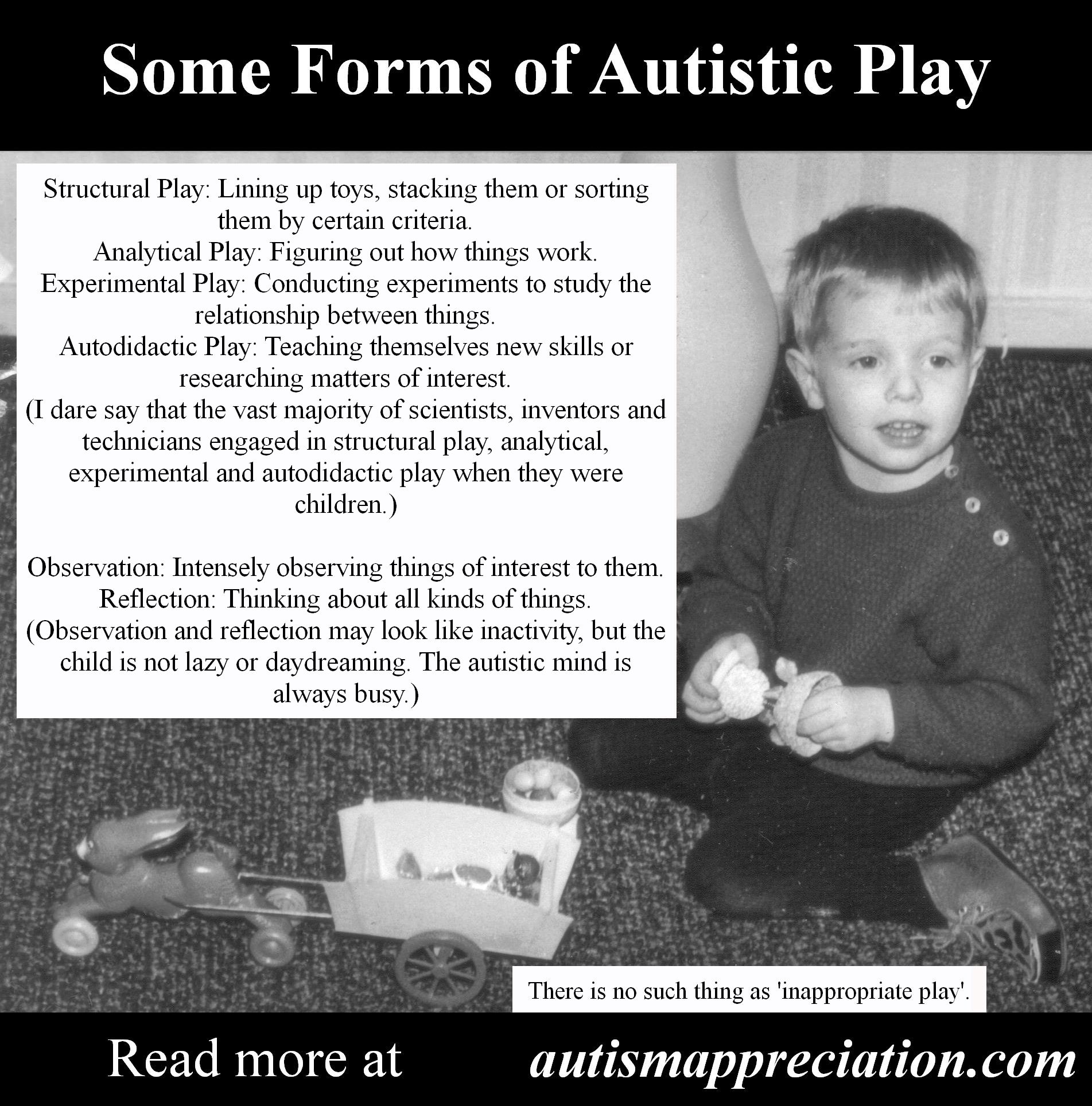

Play

According to the Collins dictionary play consists of ‘games, exercise, or other activity undertaken for pleasure, diversion, etc’, and Wikipedia (who, according to their citation, took the definition from Catherine Garvey’s book Play) states that ‘play is a range of intrinsically motivated activities done for recreational pleasure and enjoyment’.

As soon as your child receives an autism diagnosis, professionals will get you to look at everything they do through a medical lens and see phantom problems everywhere. If you approach the situation rationally and accept your child’s individual nature, you will often find that there is no problem at all.

For example, your child’s advanced vocabulary may suddenly become ‘pedantic speech’, their formerly appreciated organisational skills may henceforth become ‘an inflexible need for routine’, and their precious ability to concentrate on certain tasks or activities may now be called ‘hyperfocus’.

Children can develop an area of expertise or a particular talent from an early age. When these children aren’t autistic, they are considered gifted; when they are autistic, however, their expertise is pathologised as a ‘special interest’ or ‘obsession’.

But then it was discovered that the vast majority of these children are autistic which caused hysteria. If this seemingly advantageous ability is linked to autism, there must be something wrong with it, scientists concluded, and so it became a syndrome called 'hyperlexia'.

Similarly, early maths skills are called 'hypernumeracy'.

When Jimmy is excited he flaps his hands. When he is nervous he rocks back and forth. When he is concentrating he holds his head and makes a humming sound. None of this is socially acceptable because Jimmy is autistic.

Even though stimming (short for self-stimulation) is associated with autistic people, everybody does it; only that it’s usually called fidgeting. However, most stims of mainstream people are so common that hardly anyone pays attention while those of autistic people tend to be more obvious. They serve the same purpose, though, and as long as nobody gets hurt and nothing broken, they should be tolerated as well.

You can read more about this in my Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis in which I argue that autism is a social construct for people who resist social conditioning. (Abstract: 'All children are born with individual identities, but almost all of them undergo social conditioning and are forced to take on collective identities instead. Human progress is driven by people who resist social conditioning [or are not subjected to it in the first place] and retain their individual identities at the cost of being ostracised and pathologised while those who identify collectively provide the network to spread it.')

So there can’t possibly be any wrong way to play, right?

Well, according to some people there is, at least when the child is autistic. Their play may not be as focussed on social aspects as that of others, but their type of play is also intrinsically motivated and brings them pleasure and diversion.

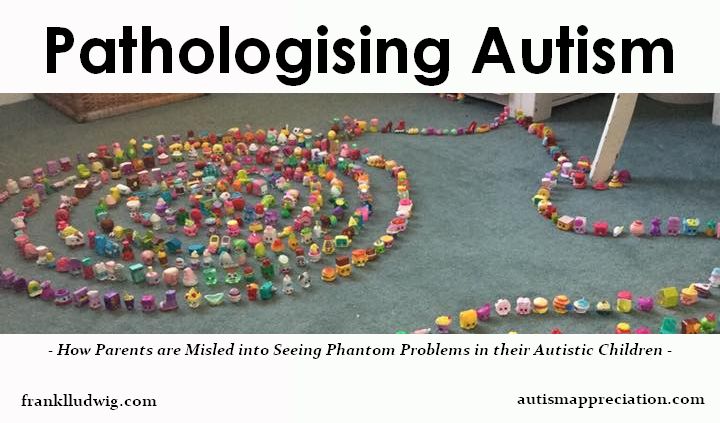

And while some educators are of the opinion that play has to support the development of skills, autistic play does this as well. An autistic child lining up their toys may hone their counting skills, create patterns unnoticed by others or sort them by a certain criterion. An autistic child spending hours observing a spider in its web (as I did when I was a child) may increase their understanding and appreciation of nature. And an autistic child permanently spinning the wheels of their toy cars may be figuring out the mechanics. We do not play purposelessly.

Pushing us to play the way others do contradicts the very definition of play by replacing the pleasure and diversion it’s supposed to bring with anxiety and feelings of inadequacy.

A perfect example of how autistic play is pathologised is this experiment conducted by the mother of Cadence, an autistic girl. She took a photograph of one of her daughter’s creations and posted them in four groups, only stating that it was the creation of a 10-year-old girl, not mentioning that she is autistic.