|

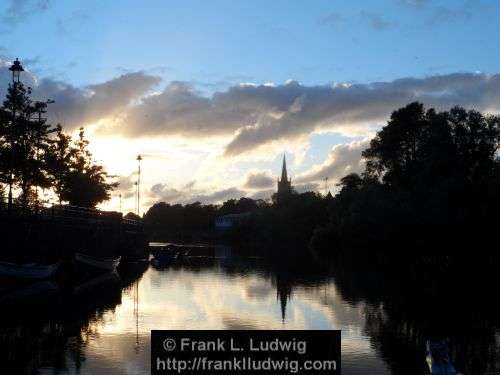

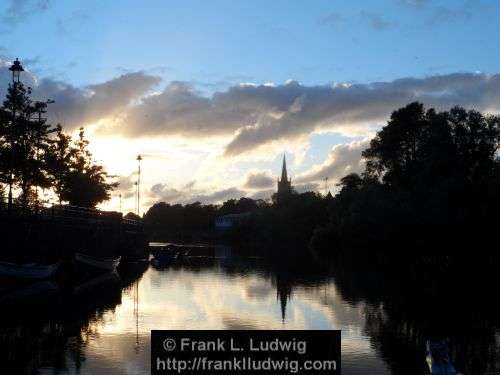

First Impression

The first I saw of Sligo

that chilly night in June

was the cathedral's tower

beneath a bright full moon.

Whichever forces drew me

were powerful and strong:

I'd finally encountered

the feeling to belong.

|

|

|

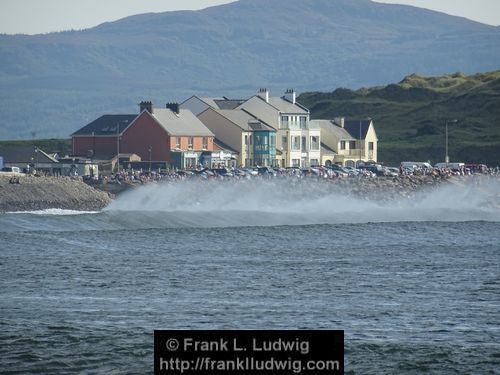

Bay Watch

Their breasts are white, their necks are long,

they're noble and they're free,

so dark and serious their eyes

that keep their mystery.

As nude as God created them

they swim the Sligo Bay,

but there's a swan most beautiful

I'll never see that way.

|

|

|

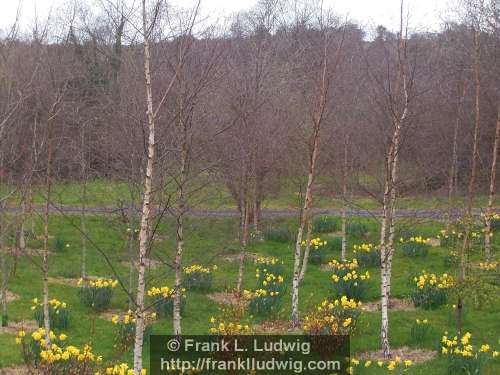

Killaspugbrone

Restless waves pet the cliff where the graveyard

is creating a life of its own,

and the April winds blow through the ruins

of the church at Killaspugbrone;

and the clouds gather over the grassland

that so leniently covers the dead,

and each daffodil, lifeless and withered,

is despondently hanging its head.

But the sun finds his way through the nimbi

like the silkworm that breaks through the floss,

and a skylark sits perched on a gravestone,

and it merrily sings on the cross;

before long it ascends to the heavens,

but I still hear its voice from the skies

as it sings of that day of redemption

when the dead and the daffodils rise.

|

|

|

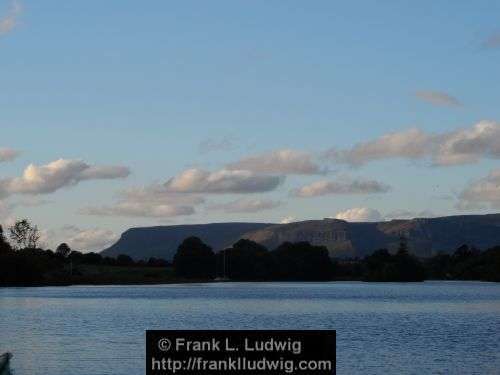

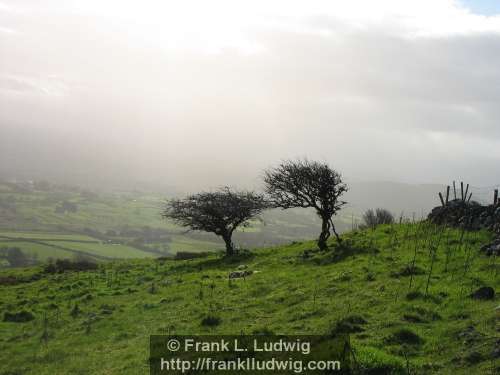

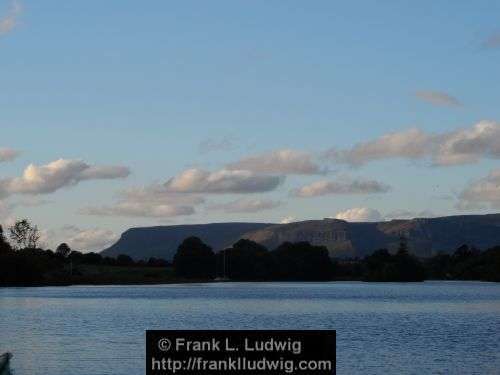

Benbulben

Where Benbulben's vanguard towers

like a prow to part the bay,

where his arctic-alpine flowers

bloom along the winding way

and the uncorrupted powers

of a people past still sway

all our destinies, the stage

now is set for one more age.

Once the mighty Dagda's table,

afterwards the hunting ground

of the Fianna as the fable

tells us, when the dreadful sound

of Dord Fiann left foes unable

to advance or move around

on his slopes, Benbulben loomed

over all he blessed or doomed.

The primeval mountain greeted

heroes fighting in the sticks,

from cursed Diarmait who defeated

the wild boar to the Noble Six;

he saw history repeated,

oftentimes without a fix,

since he came to overlook

Columb's Battle of the Book.

His majestic rock formation

oversees each main event,

be it the annihilation

the Armada underwent,

famine, war or emigration;

he, a timeless monument,

keeps the records of our strives

as he dominates our lives.

|

|

|

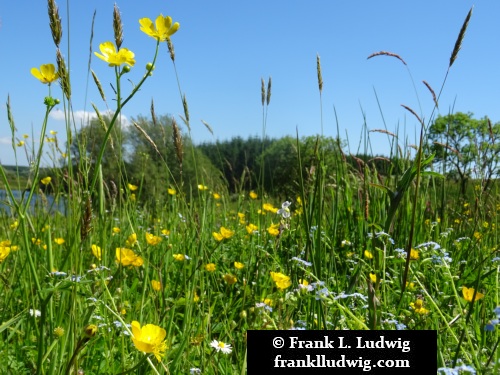

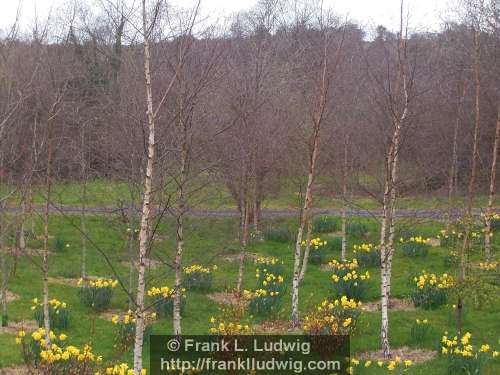

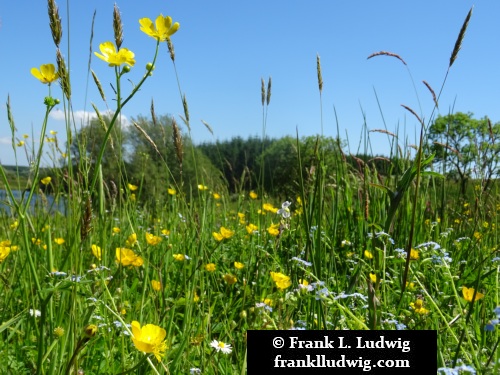

Spring in Geevagh

The buttercups of Geevagh

are headed towards the sun

like every living creature

of light since time's begun.

‘We shall stay down no longer,

unnoticed as before;

now that the winter's over,

we lift our heads once more!’

The daisies join the chorus

amidst the breeze's swing

and ragged robins calling

for everlasting spring.

‘For now we all will flourish

for an uncertain span,

so let us keep on growing

as long as we still can.’

|

|

|

The Shifting Scrod

When, God forbid, a newborn dies

before a cleric can baptise

them they're, unchristened and unblessed,

outside the churchyard laid to rest

where in unconsecrated ground

their souls by God cannot be found.

They wander through the wilderness

and take along all those, I guess,

who step upon their piece of sod

which locals call a shifting scrod.

When husbands come home late at night

to angry wives who start a fight,

they calm them in a soothing voice,

'I didn't gamble with the boys,

and I'm not drunk, I swear to God:

I stepped upon a shifting scrod.

Through time and space I, led astray,

have lost my mind and lost my way

till, fearing that my soul would burn,

by grace of God I could return.'

Many a man they did enthral,

and some have not returned at all,

but those who have had altered lives,

estranged their children and their wives

and lived their lives, for all it's worth,

in limbo right here on this Earth

while no one knows where they will stay

once God has held his Judgment Day.

No peace will come to him who trod

carelessly on a shifting scrod.

|

|

(

It is most likely that the term scrod

derives from the Irish word scraith

, meaning turf

.)

|

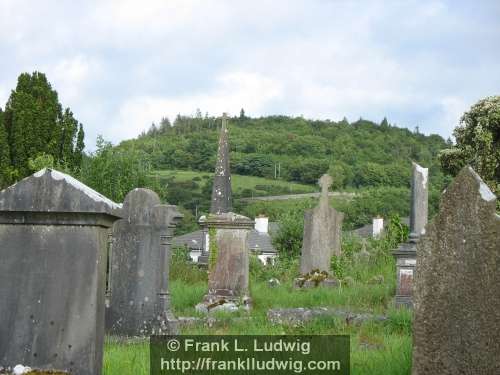

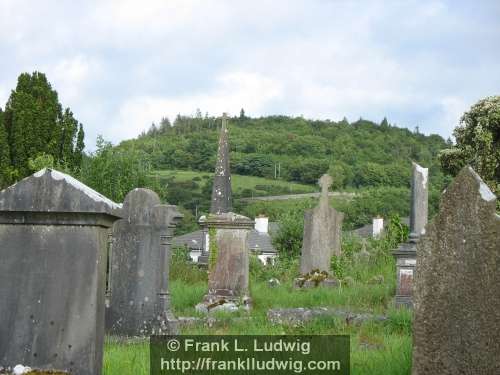

To Those Resting in Carrowmore

You watched over your queen and gave

your best to let her rule the wave

and all it is enclosing;

how does it feel, oh ancient brave,

when cows are gazing on your grave?

You have been fighting for Queen Maeve

when men and women didn't shave

nor trimmed their hair for fashion;

how does it feel, oh ancient brave,

when cows are grazing on your grave?

You have been resting in your grave

for many thousand years and save

your strength for her revival;

how does it feel, oh ancient brave,

when cows are lazing on your grave?

|

|

|

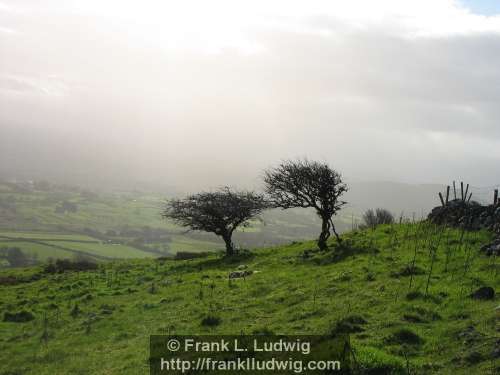

Snow on the Dartry Mountains

I shall leave while the winter is calling

his elements forth, one by one,

while the snow on the Dartry Mountains

still reflects the white light of the sun.

I'll return when the daffodils waver

to the song of the nightingale

and the snow on the Dartry Mountains

has melted and flows through the vale.

|

|

|

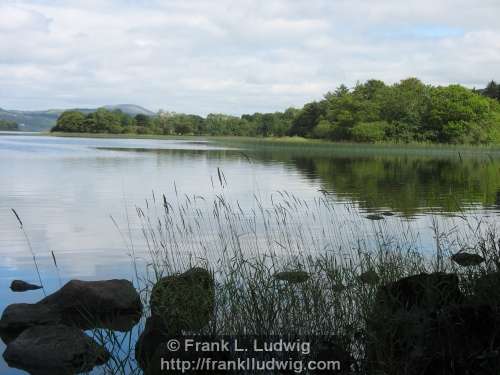

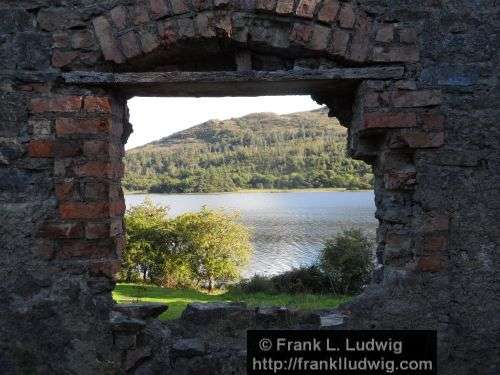

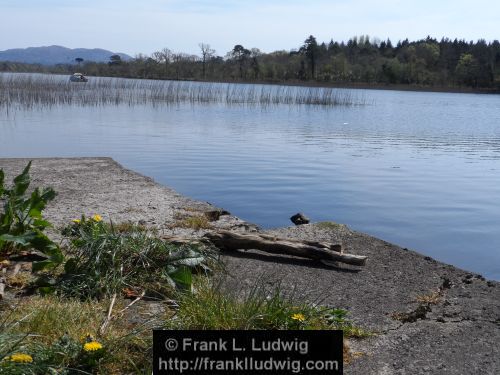

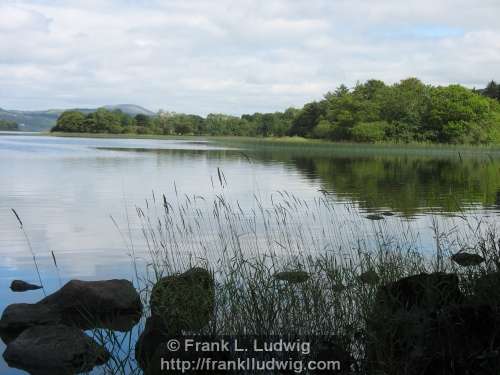

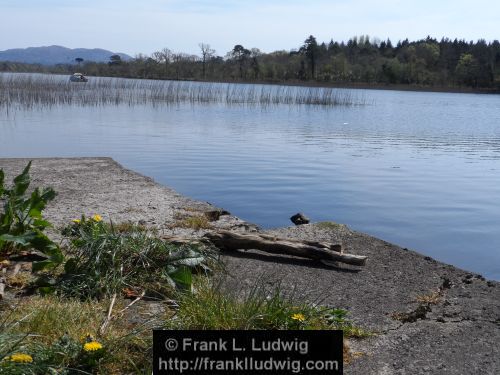

Lough Nasool

Framed by gorsed fields and evergreen

coppices thriving in the cool,

there lies a prehistoric scene:

the stony shore of Lough Nasool,

the lake that every hundred years

mysteriously disappears.

Between the hillocks you will find,

too grand to be interned by words,

another world to seize your mind,

teeming with copious fearless birds:

swallows swoop down before your eyes

and larks shoot up into the skies.

Hoofprints of generations show

this is a place of life; a lot

of those who visit do not know

that there are times when it is not,

when you can see the lake's demise

in a deserted paradise.

Here Balor of the Evil Eye

was slain, the God of Death; this ground

absorbed the poison of his eye

that dries out everything around

centennially, so we'd recall

that Death is living after all.

But in the Year of the Quiet Sun,

threescore ten years before its time,

in one large cloud the lake was gone

and sought a continental clime

to christen a poet across the sea

and call him to his destiny.

|

|

|

The Lake of the Enchantment

To be back where worries wander

off without a faint goodbye,

where lacustrine spirits squander

peace beneath the starry sky,

where no inconvenience grieves me

as I watch the evening's cool

shadows of the day that leaves me

at the shores of Lough Nasool,

To be back where the contagious

busy stillness of the lake

and its waters from the ages

keeps the watchful mind awake,

to be back on poet's duty

where no imperfection mars

Nature's unintended beauty

underneath the dripping stars.

|

|

|

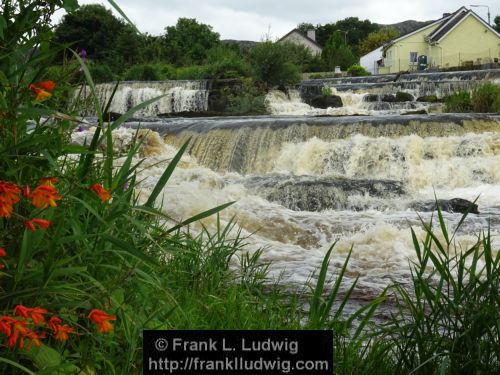

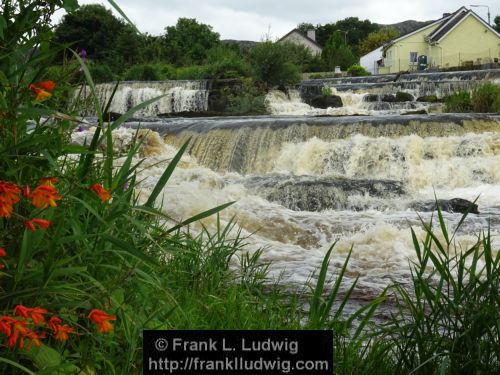

Ballysadare Falls

The salmon leap (while they still can) with pride,

performing acrobatics in midair;

they fear no weir and swim against the tide

at the falls of Ballysadare.

Montbretias tangerine the grassy bank

that sites the looming ghost estate, and there

butterfly bushes form a purple flank

at the falls of Ballysadare.

And as you turn your eyes towards Knocknarea,

the summer breeze caressing face and hair,

you feel the gushing rapids' cooling spray

at the falls of Ballysadare.

You watch torrential water raging through

the peaceful village though it knows not where

the current takes it, very much like you

at the falls of Ballysadare.

|

|

|

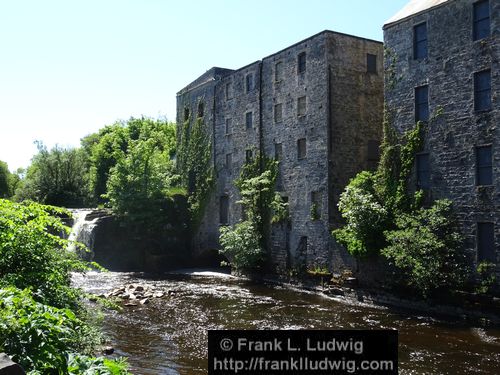

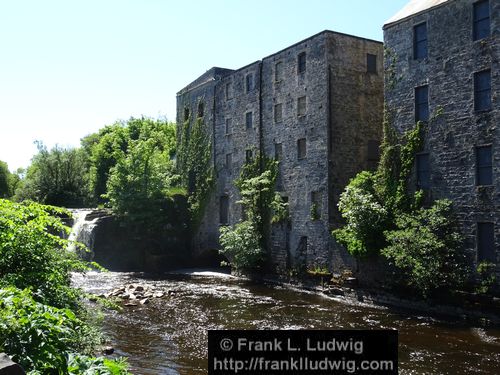

The Mills of Collooney

Grotesque mountains enclose the green valley

where the mills of Collooney once stood,

grinding corn for oppressed and oppressors

at the river that runs through the wood.

And the waters still flow through the village,

and the wood and the mountains endure

where the tireless mills of Collooney

once were feeding the rich and the poor.

But the wheels are removed and stand idle

like a church bell deprived of its chime

as the tireless mills of Collooney

have been ground by the Mill of Time.

|

|

|

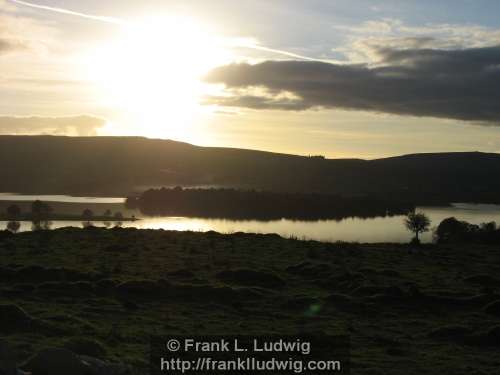

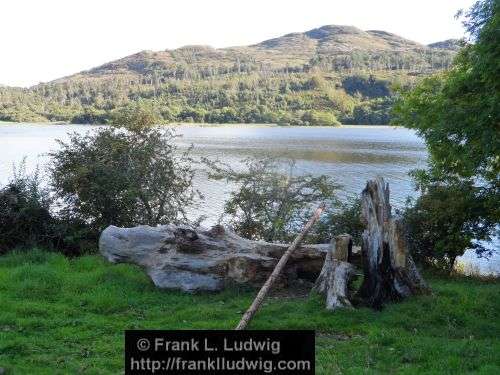

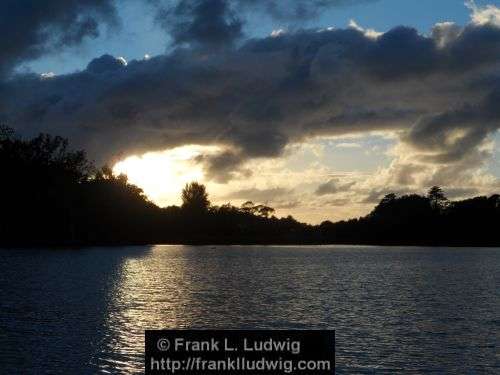

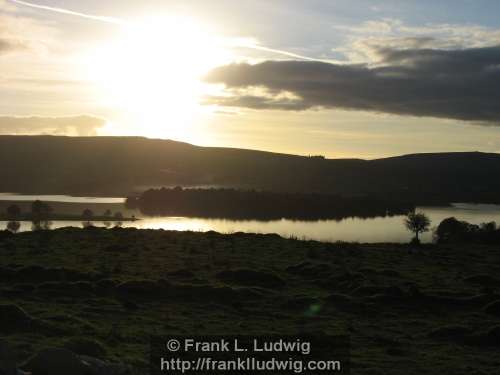

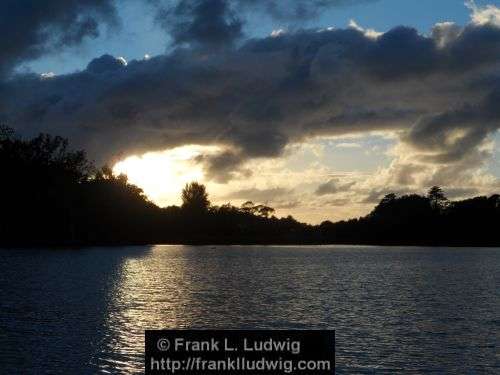

Dusk at Lough Arrow

The playful waters of Lough Arrow

lapped softly at its grassy banks,

a swan sailed swiftly through the narrow

gap in the reeds that brushed his flanks,

and in those reeds a tufted duck

guarded her nest where she was stuck.

The crows have combed the field intently

from which a solitary cow

came down to quench her thirst and gently

low at the setting sun, but now

the hustles of Lough Arrow cease

amidst a world that knows no peace.

|

|

|

Hotel Silver Swan

Blue was the river that rolled by

and blue the sky above,

an open welcome caught the eye:

that's where I met my love.

Now doors and windows are nailed shut,

grey is the sky above,

the tired river grumbles, but

it's where I met my love.

|

|

|

From Sligo to Glencar

The sun smiles brightly from the bluest skies:

this is the day to seize the day,

and so I walk along the busy road

to drink the beauties life provides.

Ignoring all impatient motorists,

I breathe the air of wood and sea,

and with the poet's heart I strongly feel

the power of the quiet things.

The craggy mountains are all dressed in firs,

in grass and gorse, and far and near

are daisies flanking streets and little brooks

and bluebells ringing in my eyes.

And after miles and miles I reach the lake

whose beauty crowns the pleasant walk,

sit down beside the water and refresh

my senses and my tired feet.

Soon two mute swans enjoy my company

while every now and then some cars,

trespassers from a poorer world, rush by,

but pass too fast to break the peace.

And on I walk to see the waterfall

that's coming down the ancient rock:

the vibrant waterfall is grey with youth,

the ancient rock is green with age.

A tourist brings his family: he puts

them all beside the waterfall

and takes a snapshot, then they turn around

to hurry to another sight.

Barbed wires separate me from the brook

that's leading to the waterfall,

but I have climbed barbed wires all my life

to get the fragrance of this world.

And in the silence of the little stream,

surrounded by the whisp'ring trees,

uniting with the forces of the Earth,

I rest and let my spirit roam.

|

|

|

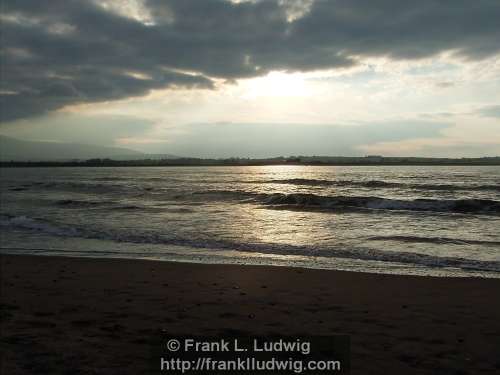

Sligo Bay Sunset

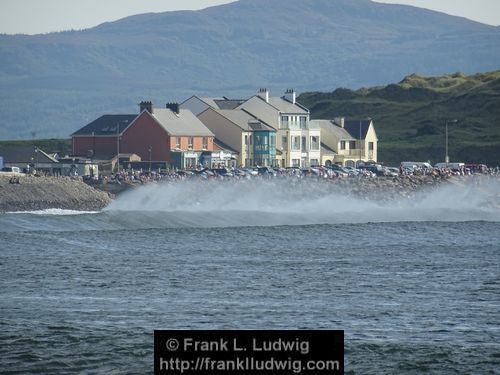

When you watch the sunset at the harbour

with its sailing boats against the clear

sky, remember that in times of famine

things were less idyllic at the pier.

Those who felt that Ireland held no future

for them gathered at the harbour gate:

overcrowded coffin ships were leaving

for a better world or grisly fate.

That was in the distant past, however,

and as you admire the day's remains,

you won't see a soul without a future,

for today they leave on aeroplanes.

Therefore nothing blemishes the scenic

quietude out here at close of day,

and you can enjoy the tranquil stillness

when the sun sets over Sligo Bay.

|

|

|

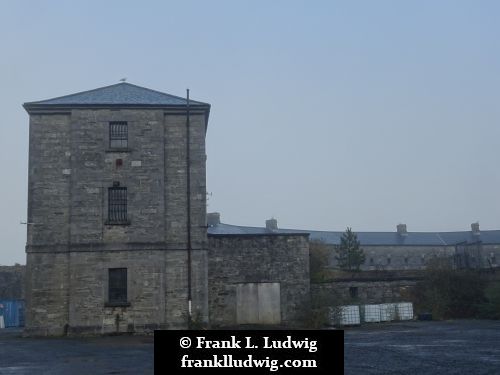

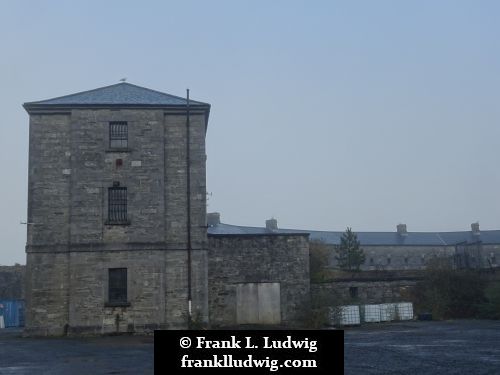

Cranmore Hotel

When I refused to recognise the court

they sent me down to Sligo to rethink;

Cranmore Hotel they call that fine resort

where I was housed and haven't slept a wink.

Nobody's hospitality could fail

as terribly as that of Sligo Gaol.

The bed they gave me felt like it was made

of cobblestone; I never closed an eye,

and in the morning I could not persuade

the guards to change the wretched mattress. 'Why?

You made your bed, now lie in it!' - No tale

of sleepless nights beats that of Sligo Gaol.

The scenery is great, and if I stand

upon the shaky table, I can see

the hill of Knocknarea amidst a land

much like my own which is so dear to me,

but little pleasures cannot countervail

the score of waking nights in Sligo Gaol.

Then spring had sprung the day when Helen came

to see me, and she brightened up my cell's

interior and set my heart aflame,

but still she wants to marry someone else.

I tried to sleep that night - to no avail,

partly due to the beds in Sligo Gaol.

Let it be known so all can read and weep

that the three weeks he spent in Sligo were

three weeks that Michael Collins didn't sleep,

an inconvenience I would not confer

upon my foes; now I've accepted bail

so they can buy new beds for Sligo Gaol.

|

|

|

A Song in Times of Famine

Potato blight in Ireland – we all know what that spells:

not just the spuds are blighted since we have nothing else!

Who still has strength to labour, if just for bed and board,

is tending well-fed cattle to feed his British lord.

But do not feel disheartened to know our fate is sealed,

for soon we shall be resting in Widow Touhy's Field.

All those who can afford it sail to the Promised Land

or the invader's country to feed their people and

will anxiously be waiting for news with bated breath,

grateful for all their children who didn't starve to death.

But you and I are going where walls of earth will shield

us from the coming turmoil in Widow Touhy's Field.

The fancy folk are buried amongst the gulls and swans:

the Catholics in the Abbey, the others in St John's,

where monumental coffins protrude from shallow ground

and ancient skulls and bodies lie scattered all around.

But we shall hear sweet music when harvesting our yield,

and crows will be our consorts in Widow Touhy's Field.

|

|

|

National Famine Commemoration 2019

Commemorations provide a great platform

to convey the impression of empathy,

especially when it comes up to elections,

and today was no different, as we could see.

The fact many tenants were cruelly evicted

by foreign landlords they couldn’t pay

to be left without places to live was remembered

by those who evict their own people today.

The fact there was plenty of food on this island

which, by those who’d annexed it, was carried away

as the natives were starving to death was remembered

by those who starve their own people today.

The fact that a million were leaving the country

to find more hospitable countries to stay

and make a living in was remembered

by those who drive out their own people today.

As the plaque was unveiled and the tree was planted

by the river, I wondered in dismay,

‘When will people start commemorating

the needless victims of today?’

|

|

|

The Maid of Breffne

I'll be taking the Maid of Breffne today

since I know for sure she'll go all the way

along the blue Garavogue's verdant strand

on which the colourful mallards land.

And she blows her horn through the midday air

from where she would ride at Riverside

all the way to the fair in Dromahair.

And on she is rolling past the tall

green trees forming Doorly Park and all

along the lush shoreline of Lough Gill

where the herons catch fish and always will.

And she blows her horn through the midday air

from where she would ride at Riverside

all the way to the fair in Dromahair.

Her wheels paddle onwards at full steam

to the mouth of the Bonet and turn upstream

where the swans make way for the vessel that brings

her passengers to the village that swings.

And she blows her horn through the midday air

from where she would ride at Riverside

all the way to the fair in Dromahair.

|

|

|

Hungry Rock

If you decide to walk to Sligo Harbour,

a bag with your belongings on your back,

trying to get the ship, east of Coolaney

pause for a little moment on your track;

a boulder called the Hungry Rock is standing

beside the winding road, and if you throw

a stone against it, you will not go hungry

until your journey's end, as locals know.

And if you're lucky someone who can spare it

may, as he passed, have left a loaf of bread

on top of it to feed the poorer craturs

who hardly can remember being fed;

but if you're in the fortunate position

to have a loaf to spare yourself, then do

the same without reserve or hesitation

for those poor souls who need it more than you.

|

|

|

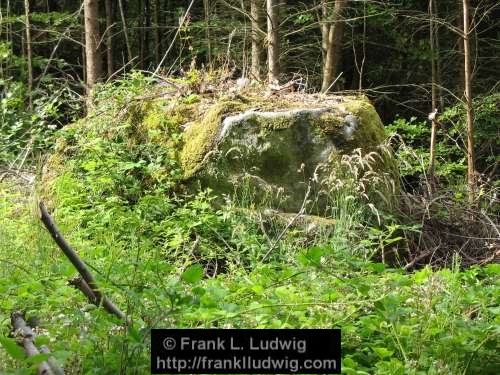

The Fairies of the Glen

Right at the foot of Knocknarea

the ramblers hesitate:

hidden amongst the thicket stands

a rusty iron gate.

It looks like it is leading nowhere,

but there's a path that will

show you a world outside this world

where Time and Earth stand still.

Thatched by enormous trees that witnessed

the dawn of humankind,

the Glen reveals a rugged beauty

that captures eye and mind.

Dwarfed by the soaring walls through which

you glimpse at distant skies,

you feel that in the undergrowth

there are a thousand eyes.

Wading through grass and mud, you quickly

sense with each breath anew

the presence of the little people

who keep their eyes on you.

Although they hide and will not show

themselves to any man,

you know you’re closely being watched by

the Fairies of the Glen.

And as you leave this magic place,

it whispers from the fern,

‘All those who don't disturb our peace

are welcome to return!’

|

|

|

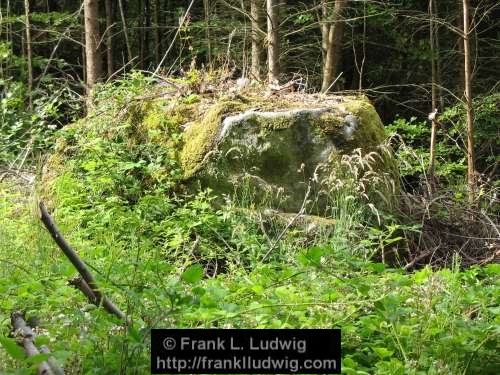

From Thebes to Lisheenacooravan

The watchful guardian awoke Thutmosis,

‘The queen was taken from her sacred tomb;

if she is not returned before the Khoiak,

she'll be condemned to everlasting doom!’

The pharaoh started up, breathed deeply, rose from

his sealed sarcophagus, and he exclaimed,

‘Not Neferura, dearest wife and sister!

No peace shall be on him who's to be blamed!

‘My chariot at once,’ Thutmosis ordered.

‘Make haste, make haste, don't leave me in the lurch!’ -

‘Where will you search for her?’ - ‘Her ba is shining

bright as a star, I do not have to search!’

When Owen Phibbs at last returned from Egypt

home to Lisheenacooravan, he brought

a treasure of old daggers, swords and mummies,

attracting more attention than he'd thought.

He laid them out upstairs beneath the skylight

and called it his museum. ‘You're a grave

robber,’ his father said. ‘Have you not heard of

the punishment?’ - ‘I’m back now, so I'm safe.’

The pharaoh's chariot raced through the night sky

en route to Sligo and approached the bay,

reached Seafield House and burst into the chamber

where his belovèd Neferura lay.

As the foundations trembled and the china

broke into bits, the Phibbses, all in fear

of burglars or an earthquake, went to follow

the unholy noise, ‘What's going on in here?’

Thutmosis faced the family in anger,

‘You robbed my consort from her resting place

and of her afterlife; unless I take her

back home, I ne'er again shall see her face!’

That very moment, through the open skylight

an owl flew in; it rested on the queen

and pecked her heart out. ‘Dammit, Ammit!’ shouted

the king but couldn't stop it fleeing the scene.

‘What in God's name was that?’ - ‘That owl was Ammit,

a demon. Now,’ the pharaoh caught his breath,

‘without her heart, my consort can no longer

travel with Ra; she died the second death.’

‘I am so sorry,’ Owen told Thutmosis,

‘I wish that there was something we could do.’

His mother blessed herself; the fuming pharaoh

yelled from his lungs, ‘She died because of you!

‘I won't find peace without her, yet I have to

travel with Ra until the end of days,

but I'll send back my chariot each midnight

which shall remind you of your sinful ways!’

And back it came, night after night. The clamour

soon drove away the gardener, their prized

domestic servants, and the Phibbses followed,

unable to expel the poltergeist.

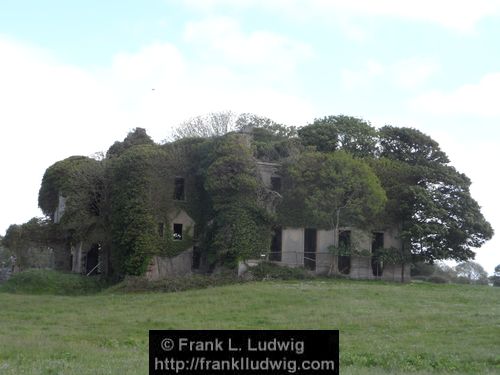

Time watches. Seafield House is long abandoned,

and birds nest in the trees that grow inside,

the winds blow harshly through its stately ruins,

and all one hears at daytime is the tide.

But after dark a grim unearthly clatter

shakes its foundations every night anew

as, drawn by passionate Arabian horses,

the pharaoh's chariot is passing through.

|

|

|

The Spray of Mullaghmore

The haggard ageing lady

staggered along the shore,

unwittingly embracing

the spray of Mullaghmore.

When she was young, her parents

had died of cholera,

and she was left to fend for

her smaller siblings, far

from anyone who'd help her,

and even though she strived

to nourish and support them

not one of them survived.

At night she would be walking

along the lonely shore,

unwittingly embracing

the spray of Mullaghmore.

One stormy day her husband,

out of necessity,

had set out on his trawler

and soon was lost at sea;

the mourning hardened widow

after the tragedy

took up the job of feeding

a dwindling family.

Night after night she wandered

along the roaring shore,

unwittingly embracing

the spray of Mullaghmore.

All her surviving children

had boarded ships to reach

America which grieved her,

but she'd encouraged each

of them to seek their fortune

across the ocean when

the country hungered, never

to hear from them again.

At midnight she still rambles

aimlessly at the shore,

unwittingly embracing

the spray of Mullaghmore.

|

|

|

The Death Wave of Cuil Irra

The August sun unclosed his gates

and smiled on Sligo Bay

where six young women from the States

enjoyed their holiday.

It wasn't since their childhood that

they'd seen their native land,

and with a blithe innocuous chat

they sauntered towards the strand.

And there they all tied back their curls,

preparing for a swim,

when an old man approached the girls,

his mien upset and grim,

‘Don't swim today! No one is safe;

out on the sea, not far

from here I saw a dark black wave -

the Death Wave of Cuil Irra!’

The women giggled, and they said,

‘Old men are so naive -

there's not a myth or legend that

these folk would not believe!’

And as the sound of his heavy boots

was slowly fading away,

they slipped into their bathing suits

and headed for the bay.

One stayed behind - she didn't heed

the others who'd beseech

her to join in; she'd sit and read

and watch them from the beach.

And further out, and further out

they swam, their spurs to earn;

they didn't hear their comrade shout

who urged them to return.

And where the water nymphs abide

in the shadow of Queen Maeve,

they saw a tall blonde lady ride

upon a sombre wave.

Her hair was shining like the sun

that framed her naked breasts,

and with her gentle smile she won

the affection of her guests.

Her eyes were blue as is the sea,

the spray pearled off her skin

as she commanded, ‘Come with me

to the Island of Maguin!’

The women watched her, willingly

and keenly following,

but halfway to the island she

became a different thing.

Her golden locks turned into snakes,

foul scales appeared beneath

her waist, and like a row of stakes

she showed her canine teeth.

The frightened women turned away

in terror, and they fought

to escape her grip, but soon the bay

claimed what it long had sought.

And seconds later they were gone

to share the icy grave

of all who e'er laid eyes upon

the Sorceress of the Wave.

No one encountered her of late;

she hides from sun and star,

but somewhere she still lies in wait –

the Death Wave of Cuil Irra!

|

|

|

The Mermaid Rocks

The O'Dowd in autumn's glowing

twilight wandered all alone,

musing on the things worth knowing

at the beach of Enniscrone.

There the gentle waves were bringing

weal to those who seize the day,

and a naked girl was singing

on a rock beside the bay.

The O'Dowd who raptly eyed her

marvelled at her voice and shape;

he sneaked closer, and beside her

on the ground he saw her cape.

He considered this pelagic

mermaid as a lucky gift

since her cape contained the magic

that allowed her shape to shift.

So he hid it with the notion

of a conquest, and he cried,

‘Now you have to shun the ocean -

come with me and be my bride!’

The O'Dowd and Meara married

while she wore her human skin,

but the homesick merrow carried

still the love for her own kin.

Meara did the cleaning, cooking,

and she brought his food and ale;

all the while she kept on looking

for her cape, to no avail.

She was seven times a mum in

just as many years gone by,

and the youngest one, a gamine,

was the apple of her eye.

Once she called in joyful temper,

‘Mum, come here and have a peek:

at the bottom of the hamper

I have found the cape you seek.’

Meara put it on, restoring

her belovèd mermaid skin,

brought her children to the roaring

sea and told them to get in.

‘But we don't have gills,’ the older

children said, inclined to stay;

she turned each into a boulder

which can still be seen today.

Meara and her youngest daughter,

without ever looking back,

went into the icy water,

leaving not a trace nor track.

|

|

|

Where Fairies Go to Die

Where time is anything but short

under the azure skies,

I stood amidst the fairy fort

and closed my weary eyes.

I turned around three times and called

for a sane world, stood still,

opened my eyes and was appalled:

my back faced towards the hill.

My wish declined for lack of spin,

I sauntered up to see

the hillfort on the Marilyn

that's known as Knocknashee,

its limestone ramparts and its grand

wild flowers in the breeze

and its deserted huts that stand

amongst the windswept trees.

And where the fairies once advised

the gods and kings around,

Fomors and giants exercised,

I couldn't hear a sound;

some say they heard amongst the scree

a whisper or a sigh

in the wilderness of Knocknashee

where fairies go to die.

They say they hide behind the shales

and watch our every move

and show themselves and tell their tales

to people they approve.

And as I stood beside the cairn

atop of Knocknashee,

I watched the Moy roll by and turn

en route to find the sea.

Where anything but time is short,

the little people dwell,

and at their hidden fairy fort

life and the world seem well.

Just once again I'd like to see,

before my time goes by,

the wilderness of Knocknashee

where fairies go to die.

|

|

|

The Dragon of Knocknarea

There is a wood on Knocknarea below the lofty grave

of someone who (as people say) will come again: Queen Maeve.

Each votary who climbs the hill puts on her mound a stone,

and when the number's full, she will rise to reclaim her throne.

And in the thicket of that wood where no man dares to stroll

(and, let me tell you, no man should), there, in a hidden hole

a dragon lives beneath a yew, begotten by her spell,

who has been seen by very few, and fewer live to tell.

He guards the cairn with watchful eyes; if anyone comes near,

he lifts his head and slyly spies on those who have no fear,

and if they bring a stone and bow before the Queen of Man,

he will unraise his scaly brow, lie down and sleep again.

But someone who disturbs the peace of her reposing bones

by climbing up the mound he sees or by removing stones

kindles the frenzy of the brute; at once the dragon will

take a deep breath and blow the crude intruder down the hill!

And on the open plateau he'll be hit by stones, exhale,

and, fleeing towards the wood, he'll feel the dragon's mighty tail

smashing his skull against the boles of ancient trees; a sharp

pain is endured by him who rolls down the precipitous scarp!

And if the beast should get irate, there's no one he would spare -

he will arise and desolate the land around his lair,

he'll whip the bay round Knocknarea to make its waters swell;

the two-faced ocean will obey by drowning beach and dell.

Many a man has paid the price for braving pow'rs of yore,

but those of us who met him twice will still come back for more!

|

|

|

Cockcrow in Killawaddy

When the cock in Killawaddy*

doesn't crow at dawn, it's said,

mischief lurks, so everybody

skips their work and stays in bed.

Days like these leave their indenture

on the village through all ranks

as the hidden people venture

out to play their little pranks.

When this happens on a Sunday,

which it often has, alas,

some stay home to make it fun day,

others still head out to Mass.

Seeing there's no congregation,

Father Brennan stamped his feet,

mumbled something of damnation

and marched out into the street.

With his walking stick he strongly

knocked at every single door,

calling out the ones who wrongly

had abstained from Heaven's store.

‘Father, hidden people's missions

cost us all a heavy toll.’ -

‘Oust your pagan superstitions

lest the Devil have your soul!’

Once the sheep had been collected

who had left him in the lurch,

they all followed as directed,

but they couldn't see the church.

As they gathered where in recent

times it stood, they gasped, of course,

while they witnessed some indecent

laughter from an unknown source.

|

|

*Killawaddy is a fictional village in Co Sligo, first described by Joe McGowan in The Hidden People.

|

Lough Nasool Unplugged

Two score two years ago, the summer I

was born, not e'en a little pool

remained where, out of turn, a lake went dry:

they'd pulled the plug on Lough Nasool.

One score one year ago, the summer I

first came to Sligo was quite cool,

yet, out of turn, the mystic lake went dry:

they'd pulled the plug on Lough Nasool.

This summer I keep wondering about

the coming lesson in life's school,

for something's up, of this I have no doubt:

they pulled the plug on Lough Nasool.

|

|

|

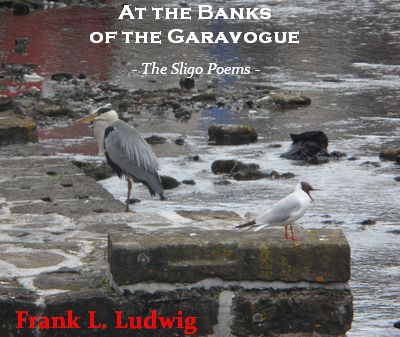

At the Banks of the Garavogue

At dusk, when the shadows are falling

under street lights in Doorly Park,

you pause as you hear someone calling

your name through the trees in the dark;

turning round, you will notice the funny

physique of a pitiful rogue

who asks for a smoke and some money

at the banks of the Garavogue.

The wind picks up speed, and you shiver

besides the stream and stand still

near the crannog astern of the river

where the waters approach from Lough Gill.

A boatman is cursing the weather

and casts out his homemade drogue

as the ominous storm clouds gather

o'er the banks of the Garavogue.

In the distance you hear the fright'ning

thunder rolling to mark his domain,

accompanied by the first lightning.

In seconds you're drenched by the rain,

and as the thunder comes nigh, go

as fast as you can in your brogue

and return to the shelter of Sligo

from the banks of the Garavogue.

|

|

|

The Dunes of Streedagh

The restless dunes of Streedagh

look down upon the sea

as they are rearranging

themselves persistently.

Like the unsettled ocean

is moving with the tides,

the restless dunes of Streedagh

form as the wind decides.

The shifting sands keep changing

at random with great zeal;

some secrets they’ll uncover,

some secrets they’ll conceal.

Though life forms they are hosting

may strongly disapprove,

the restless dunes of Streedagh

are always on the move.

|

|

|

When the Fleadh Returns to Sligo

Sligo Town will buzz with fiddlers,

visitors will tap their feet,

boys and girls in classic costumes

will be dancing in the street;

when the Fleadh returns to Sligo,

you and I once more shall meet.

Céilí bands will be competing,

gifted children without qualms

will be showing off their talents

as the maids show off their charms;

when the Fleadh returns to Sligo,

I shall hold you in my arms.

Sligo will be celebrating

with its guests from far and nigh,

there will be, before it's over,

lots of fireworks in the sky;

when the Fleadh returns to Sligo,

we shall say our last goodbye.

|

|

|

Dromahair Road

Starlings sing their joyful chorus,

lambs are bleating everywhere,

and the sunshine warms the tarmac

on the road to Dromahair.

Through the ancient walls and hedges

I can see the distant hills

and amongst the slender birches

patches of young daffodils.

Where the persevering farmers

drove their cattle to the fair,

I must walk without companions

on the road to Dromahair.

Looking back I see the stations

I have covered on my way:

there's the fading town of Sligo

and the mound of Knocknarea.

Soon I'll reach the Bonet, pending

like a salmon in the air,

for my fate shall be unravelled

once I've passed through Dromahair.

|

|

|

Hazelnight

When slowly rising shadows mark

the exitus of one more day

and Hazelwood lies in the dark,

the salmon play at Half Moon Bay.

And when the creatures of the night

who never have been seen by man

do what they all believe is right,

the salmon leap while they still can.

When at the old abandoned house

the spectres gather for the feud

and recommit to ancient vows,

the salmon keep their attitude.

When the magenta streaks of dawn

have brushed the void of night away,

the living rise and greet the morn,

and salmon play at Half Moon Bay.

|

|

|

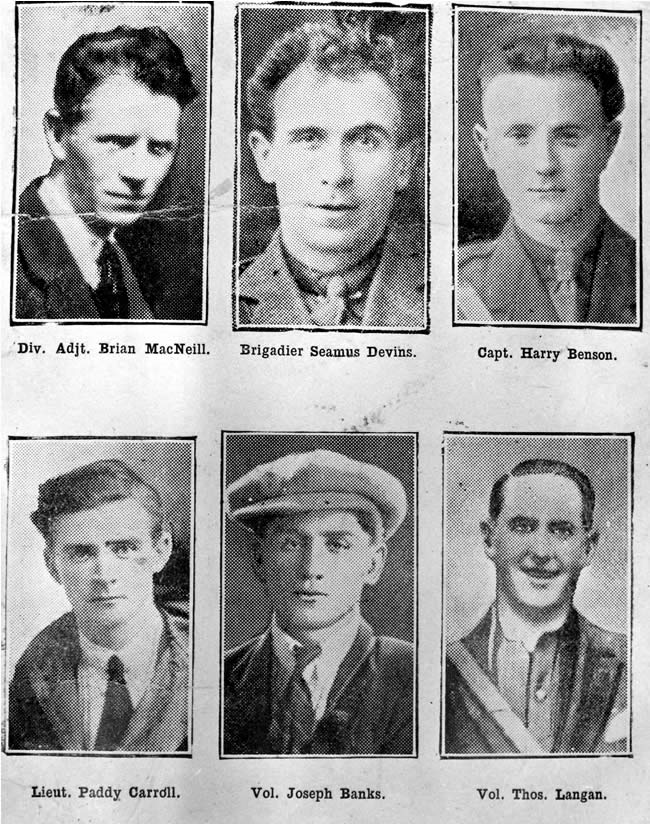

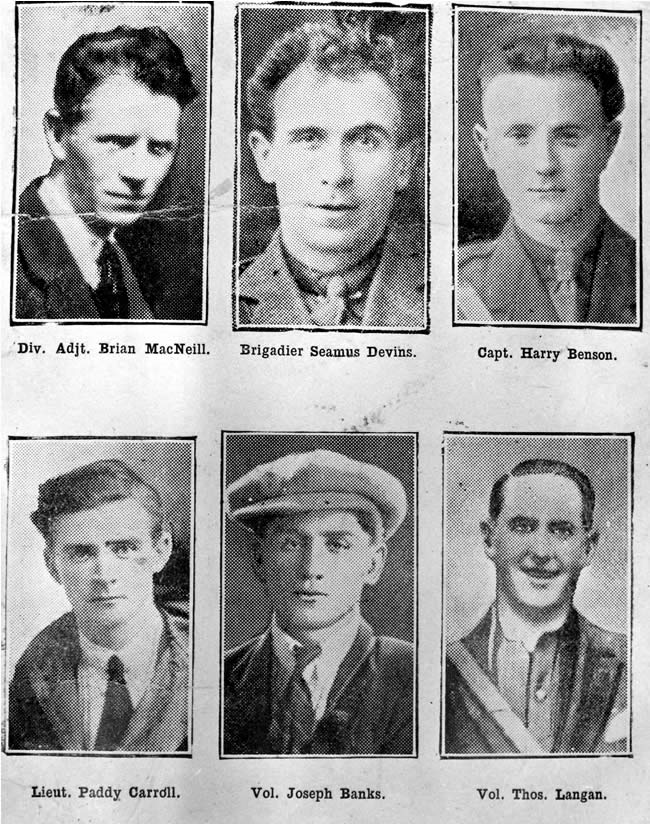

The Noble Six

The Civil War in Sligo

was over, technically:

Free Staters had retaken

the county by the sea.

But pockets of resistance

remained, true to the plight

of those who swore they wouldn’t

concede without a fight.

In an ambush staged at Rockwood,

the IRA killed three

soldiers and took their armoured

car, the Ballinalee.

When trapped beneath Benbulben,

its crew, watched from afar,

disabled and abandoned

the captured armoured car.

Here General MacEoin

advised his men to take

no prisoners and called for

buckets of blood in its wake.

It was a foggy morning

when on Benbulben’s slope

six Anti-Treaty soldiers

came close to losing hope.

Surrounded by Free Staters,

they had been forced to leave

their safe houses and head for

the overcast massif.

They planned to meet their comrades

atop the mount and make

their way down to their hideout,

the cave near Glencar Lake.

James Devins, Teachta Dála,

Joe Banks, Brian McNeill

and Paddy Carroll ascended

to face their last ordeal.

The fog grew even denser

as they approached, and so

the Free State soldiers waiting

could not tell friend from foe.

Identified as rebels,

the four surrendered and,

disarmed and handcuffed, witnessed

how things got out of hand.

One Free State captain called for

some volunteers to kill

the prisoners; nobody

would execute his will.

He sent his soldiers forward,

then shot the four and claimed

their valuables and left them,

unmoved and unashamed.

Two others, Harry Benson

and Thomas Langan, too,

went up the slope to meet with

their friends, a choice they’d rue.

Only a few hours after

the others had been shot,

they ran into the unit

who’d left them there to rot.

And like the others, Benson

and Langan who were filled

with terror now were being

disarmed, restrained and killed.

The last to die in Sligo,

those murdered in the sticks

will always be remembered

as Sligo’s Noble Six.

|

|

|

The Last Islander

Where herons stalk the playful fish

in the waters of Lough Gill,

there sleeps a densely wooded isle

of calm where time stands still.

They've called it Beezie's Island since

the ageing widow came

to live here, and not many folk

recall its proper name.

To get her pension she would row

to town, and afterwards

you'd find her in the kitchen where

she'd sit and feed the birds.

The robins, squirrels, crows and swans

who ate out of her hand

and every animal around

considered her their friend.

All visitors were welcome who

respected Beezie's pets,

and only one of them got barred

for throwing stones at rats.

And oft the local fishermen

would help her run and clean

her secret still and in return

get bottles of poteen.

When blizzards raged throughout the spring

of forty-seven, she

stayed on her island though she knew

how risky it would be.

The frozen lake had cut her off;

the smoke soon ceased to rise

from Beezie's chimney, and her friends

sought ways to bring supplies.

Gardaí and locals hired a truck

to haul a boat and fill

it with some firewood, coal and food

at the shoreline of Lough Gill.

A dozen men carefully pushed

the boat across the lake,

ready to jump aboard in case

the fragile ice should break.

Huddled in sheets between her cat

and dog, they found the old

lady; her pets had died before

of hunger and of cold.

Taken to Sligo General

she soon became a star:

to meet the Lady of the Lake

folk came from near and far.

One evening, just outside the door,

as Beezie fetched her comb,

she heard a nurse suggesting they

should put her in a home.

Beezie discharged herself that night

and rowed back to her isle

where she had breakfast with the friends

she'd missed for quite a while.

Though over ninety, she was full

of vigour and of wit;

she did not suffer from old age,

nor did she die of it:

One Christmas season, as so oft,

some of her friends from town

came to cut wood for Beezie's fire

and found her house burnt down.

No one has dwelt upon the lake

since the old lady's gone,

but in all things that crawl and fly

her spirit still lives on.

|

|

|

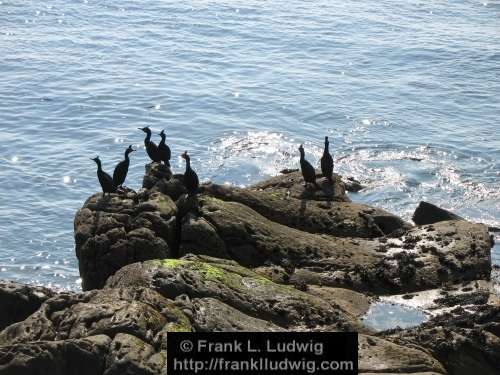

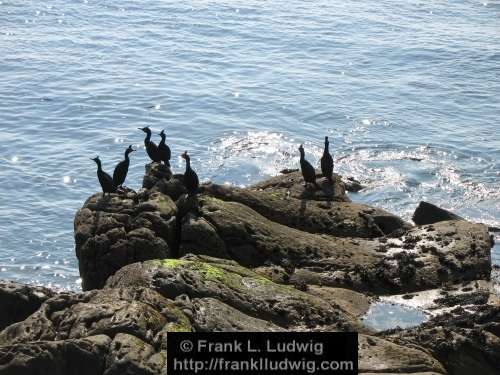

Moonshine on Inishmurray

The moonshine nurtured Inishmurray

from ages immemorial

where cormorants and gannets scurry

at ease since no raptorial

creature is there to pose a danger,

nor would a human be a stranger.

I can recall the holy well in

the island's sunlight and its cool

water, the house we used to dwell in,

the fulmars nesting near the school

and all my classmates' smiling faces

in this, the happiest of places.

But though we love our birthplace dearly,

its craggy nature and its strand,

it is impossible to merely

live off the ocean or the land,

and so for aeons we've been filling

the gap by mountain dew distilling.

Mainland police came oft to visit

the island since they were inclined

to end our trade and asked ‘Where is it?’ -

We wouldn't tell, they wouldn't find.

And yet, despite our different labels,

we made them welcome at our tables.

But on occasions they discovered

our kegs and sent our men to gaol,

so want and hardship always hovered

above us on an unknown scale;

at times they found more than the shipment

and confiscated the equipment.

Then came Gardaí; we aren't skittish,

but they, as soon we understood,

were more committed than the British

to stamping out our livelihood;

with all the still houses demolished,

our business had to be abolished.

The island life is unforgiving,

and in the end we all have swerved

from home so we can make a living;

today the moon shines unobserved

on Inishmurray as the island's

desertion caused a pensive silence.

The spirit that so long has slumbered

will never cease to live and breathe,

and though my days on Earth be numbered

which soon I'll watch from underneath,

there'll be no gravedigger to bury

my memories of Inishmurray.

|

|

|

In the Days of Seamus McLaughlin

In the days of Seamus McLaughlin

we would wait in the back of his bar

till the man himself was descending

to sit with us and tune his guitar.

And he'd carefully stick his burning

cigarette between peghead and strings,

and soon his plectrum was flying

like a hummingbird spreading its wings.

Every night was a musical journey,

and through space and time we would fly,

from the Hotel California

to the Fields of Athenry.

And he'd pass his guitar on to others

who wanted to play. We'd hear songs

sung in Basque, Swahili and Irish

at our cheerful singalongs.

Towards the end he would ask the young poet

for his Ghost Riders in the Sky

(or at least the few lines he remembered),

and as the evening rushed by

he might call for a poetry reading,

so the pipe would be put aside

as the writer took out his collection

of poems and gladly complied.

Close to after the closing hour

two Gardaí wandered in one night,

and, thinking the place would be raided,

Seamus' guests got a little fright.

But they went to the counter and ordered -

they had only come in to stay

for a Guinness, went back to their squad car

and quietly drove away.

And on Tuesdays the Trad band were playing -

the guitars quickly followed the call

of the bodhrán, and soon they were joined by

the most sensual flautist of all,

by the fiddles and pipes; the musicians

and the punters got caught by the beat,

and, with or without taking notice,

everybody was moving their feet.

When the music was over, we chatted

about neighbours or life's hectic mode

till the bell rang out for last orders:

one more smoke, and a pint for the road.

Then we slowly got up and returned to

a world of a different kind -

in the days of Seamus McLaughlin

we went home with a song on our mind.

When the Euro came in, I once mentioned

that I needed a mobile; with perked

ears he said he'd sell his for a tenner,

and I gave him ten Euros. He smirked,

'When I said it was yours for a tenner,

I meant Pound'. - I just should have known,

so I gave him another two eighty

and owned my first mobile phone.

And as soon as we laughed at first rumours

of a ludicrous smoking ban,

Seamus sold his wee pub, and we'll never

come together like that again.

Today he is playing at weddings

or in pubs round the Point, and I meet

him in town now and then when I'm shopping,

and we stop for a chat in the street.

Then we talk of the present and future,

how things should be and how they are;

but when I meet one of the others

who used to drink in his bar,

we both, caught in a spell of nostalgia,

dig up many a memory

from the days of Seamus McLaughlin

when life was the way it should be.

|

|

|

The Mystical Lady of Hennessy's Corner

‘Twas Christmas Eve for the guys from An Post

who'd returned from their rounds to the store,

full of chocolate and cake and the Christmas drinks

they were served at many a door.

John, too, stumbled out of his van; on all fours

he crawled to the office, but when

he was told he forgot a delivery,

he had to crawl back to the van.

He climbed in and headed for Ballintogher

where even the wind makes no sound,

where there's only dark woods and no living soul

for dozens of miles around.

The woods of Ballintogher

are treacherous and deep,

and no one dares examine

the secrets they may keep.

He turned at a corner, a song on his lips,

looking forward to biscuits and tea,

when a magical force changed the course of the van

and wrapped it around a tree.

The Gards soon arrived, and, testing his breath,

grew as pale as the wintery sky,

‘Dear God, you're as drunk as a sailor,’ they screamed,

‘you may kiss your licence goodbye!’

‘I swear that I had not a drop while I drove,

but after the accident

a lady appeared from among the trees

and approached me, a glass in her hand.

‘She was stately and young, with flowing red hair,

and she wore a transparent gown,

and she helped me up, and she told me, “You need

a brandy to calm yourself down.”

‘I emptied the glass in one go, and she filled

it up once again, flung her hair

and vanished into the woods again,

just like she was never there!’

The woods of Ballintogher

are treacherous and deep,

and no one dares examine

the secrets they may keep.

Since then drivers stop there on Christmas Eve,

and they wait, as the sun slowly sinks,

for the Mystical Lady of Hennessy's Corner

to bring them their Christmas drinks.

|

|

|

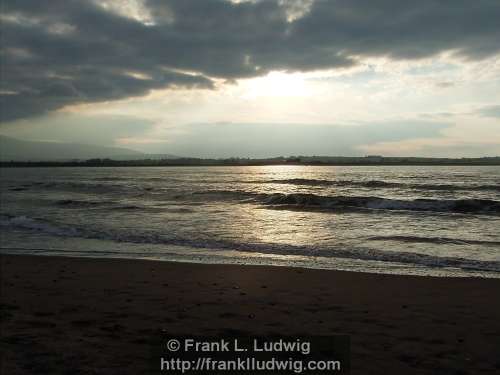

Saying Goodbye to the Summer

When we said goodbye to the summer

where the waves end their lives at the shore

of Strandhill to the subtle drum roll

of the ocean, the sun smiled once more.

There still is some light we can gather,

and all the black thoughts are postponed

to the days when the darkness of winter

casts his shadow on those he once owned.

|

|

|

Return

The dome of rain still hangs around you,

the western winds still tear the sky,

just like the day that I once found you,

just like the day I once will die,

you saddest town of all.

Your careless beauty makes me shiver,

the cans and daisies on your lawns,

and from a bench beside the river

through iron bars I see your swans,

you saddest town of all.

The clouded dark blue mantle covers

your opaque waters in the night,

for poets, suicides and lovers

the moon sends down her mystic light,

you saddest town of all.

The walls of silence still surround you,

and still the world is passing by,

just like the day that I once found you,

just like the day I once will die,

you saddest town of all.

|

|

|

The Bells Of Nagnata

In a valley near the ocean

stood the city of Nagnata,

heart of commerce and devotion;

here, in Erin's thriving gem,

the Dagda lived and his inamorata

beside the shrine his people built for them.

In a mill the men were grinding

corn while bards gave their renditions

at the streamlets that were winding

through ravines down to the sea,

from near and far the traders and musicians

arrived, becoming what they strove to be.

Mansions, roads and public places

yielded its distinguished aura,

fishermen with ruddy faces

sat on stones and cast their rods,

and over them the deities' restorer,

the Dagda governed, Father of the Gods.

But one morning when the silence

of the birds engendered pity,

when the mist rolled from the highlands

and the streets were glazed with rain,

the tidings spread like wildfire through the city

that Patrick was arriving with his train.

Chanting hymns, the Lord's battalion

marched and noisily descended

while the Dagda on his stallion

Acein knew he faced his fate,

and anxiously he held his arm extended

and told his men to close the city gate,

‘With this town I have created

one last haven of traditions,

and it shan't be desecrated

by a foreign god or priest;

Nagnata is no place for Christian missions –

we shall not be invaded from the East!’

But the clerics were not mortals

of the common disposition,

and they walked right through the portals

like a host of phantoms, and

with sheer determination and ambition

they took control of every inch of land.

Patrick and his monks selected

the location where their abbey

was supposed to be erected

while the Dagda turned around,

telling his citizens, ‘Don’t let these flabby

intruders violate this holy ground!’

Yet no weapon could undo them:

knife and axe caused no destruction,

and their arrows went right through them

like a brooklet through the fen -

at night they would dismantle their construction,

but in the morning it would stand again.

Soon Nagnata lay defeated

and strange laws were promulgated.

When the belfry was completed,

the old god warned with a frown,

‘With the first bell that tolls, this celebrated

city shall perish and its captors drown!’

On that sunny Easter morning

after they had raised the steeple,

still ignoring every warning,

Patrick's monks felt they were blessed;

but as they rang the bell to call God's people,

they heard a distant rumbling from the West.

Then the sky was set in motion,

and a sudden rain cascaded

down the vale, the savage ocean

hurried inland to reshape

the valley; on a hill the Dagda aided

his friends in building boats for their escape.

And he watched the waters rising

in the city he had founded,

watched the wild and jeopardising

torrent that had been a brook,

and while the bells below his feet still sounded,

he gave his work of art the parting look.

Dolefully he took his magic

harp, and he commenced to strum it

as his city met its tragic

end; the pensive god grew pale,

and as the raging waters reached the summit,

the Dagda and his followers set sail.

- Where the hawks and crows examine

every chimney in the mountains,

only stirred by swans and salmon,

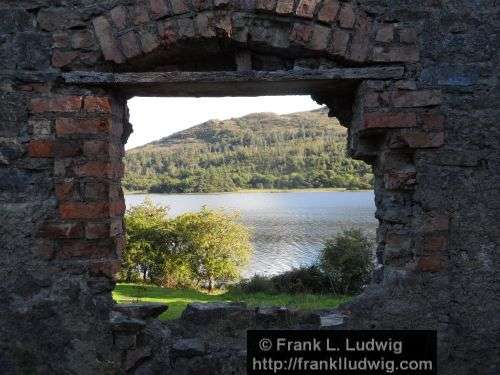

lies the surface of Lough Gill,

and on clear days their buildings and their fountains,

their streets and homes can be distinguished still.

You may see the desolated

market where they used to barter,

next to it the consecrated

shrine and abbey, ne'er to wake,

and if you hear the church bells of Nagnata,

they call you to the bottom of the lake.

|

|

|

The Raven

‘Friend of Odin, bird who rattled countless armies as they battled,

fed the balmy Gileadite and still preserves forgotten lore!

As my years and passions bygo: where,’ I asked, ‘oh where must I go

to encounter you? In Sligo, at which wild and rugged shore

can I take some pictures of your sombre beauty I adore?’

Quoth the Raven, ‘Mullaghmore.’

|

|

(To see when a poem was composed, hover over its title.)

© Frank L. Ludwig

This collection can now be ordered as a book illustrated with many colour photographs of Sligo for €16 at Lulu.