Read more on

|

Tweet

|

The fridge was buzzing in the background, the radio played the hits of the last decade, the neighbour’s dog kept barking, the frying pan was sizzling, and somewhere in the distance he heard his mother’s voice but couldn’t make out what she was saying.

There – he did it! One, two, three rows and one, two, three, four cars in each row. Now he would try to line them up so the number of rows and the cars in each row would be the same.

Suddenly his mother’s face popped up before him.

‘Don’t you listen to anything I tell you?’ she screamed. ‘I told you to get out of the kitchen with your flipping cars. I have to get dinner ready, and I don’t want to keep tripping over them!’

As Jamie put the cars back in the box she added, ‘Why don’t you play properly with your cars, anyway? We don’t just buy them for you to be lined up all day.’

He went to his room and dropped the box on the ground. He would have liked to climb on his desk and jump down a few times, but after his mother had walked in on one occasion, it was forbidden, as was jumping from his bed.

He looked around the room to see what he could do. The wall bore witness to his first spelling attempts a few months ago. However, after his father had told him he’ll never be able to read and write, he had discontinued his efforts.

Finally his eyes caught the window sill. Nobody had forbidden him to jump off the window sill, so he started putting the ornaments out of the way.

Later his mother called him back for dinner.

‘Have you washed your hands?’

He didn’t reply, which meant he hadn’t. He couldn’t see why anyone should put water or soap on their hands before eating something.

‘Jamie, how often have I told you that you have to wash your hands before dinner?’

‘Why?’

His mother dragged him to the kitchen sink to wash his hands.

‘And you really should be able to speak in full sentences at your age. Your one-word statements are what babies talk like.’

Jamie remembered what it was like when he learned to speak. The others had laughed at him or corrected him until he felt there was no point in him saying anything.

As he sat at the table, his mother put on the mixer to prepare dessert. Jamie felt like his head was exploding; he dropped his spoon, covered his ears with his hands and started screaming.

‘What is the matter with you?’ she shouted.

‘No! No!’ he yelled. Switching off the mixer, she said, ‘That means no mousse today. I really don’t get your silly fear of the mixer.’

Trying to calm himself down again, he kept rubbing his thighs.

‘And stop that fidgeting!’

The doorbell rang, and his mother went to answer it. Suddenly Jamie heard angry voices in the living room. He peeped through the keyhole and saw a stranger tying up his mother.

‘I just spent ten years in gaol because of your husband,’ the man shouted, ‘and he will pay dearly for that!’

He gagged her with her scarf and pointed his gun at her.

‘So we’ll just wait for your hubby to come home and then we’ll party, shall we?’

Jamie wasn’t sure what to do. He remembered his father saying something about calling Wan Wantu if anything happens, but of course he didn’t know how to make a phone call. Besides, if the stranger heard him, he would probably tie him up, too.

Trying to think of what he could do, his eyes fell on the cooker. He remembered his father talking about the danger of gas; how people would first fall asleep and then die if they weren’t saved by an ambulance.

If I could make both of them sleep, he pondered, I could go to the neighbours for an ambulance, and Mum would be safe.

He crept behind the cooker as far as possible and found the hose. First he tried to unscrew it, but that didn’t work, so he got the scissors.

He flattened the loose end and squeezed it under the living room door. He kept watching them through the keyhole; he saw his mother wrinkle her nose and look around, but the stranger didn’t notice anything, and after a while both of them seemed to be asleep.

Just as he was about to open the door, Jamie realised that it might be dangerous to walk across the living room; if he fell asleep as well, there’d be nobody to call the ambulance.

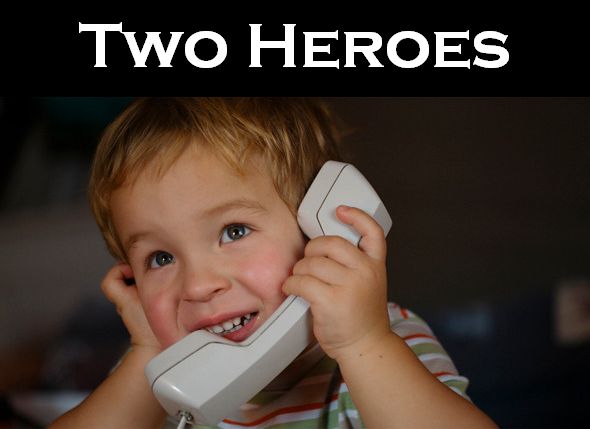

He decided to try the telephone first. He had never used it before, but he had seen his parents with it, so he might be able to figure it out.

He tried to reach the phone on the fridge, but found that his arms weren’t long enough. So he pulled up a chair and climbed on it.

When he looked at the phone, he was surprised to see that there were no letters, only numbers. He knew a few of them: one, two…

He paused. ‘One, two…’ he whispered. That sounded just like Wantu. So Wan Wantu wasn’t a name but a number.

He pressed one, one and two. He knew he wouldn’t be able to describe the complex situation, but if he managed to get an ambulance, the rest would be resolved by the adults.

When the operator asked about the emergency he simply answered, ‘Mum sleeps.’

He realised that this piece of information might not be sufficient, so he thought of the word – he had heard it before but never used it himself.

‘Did something happen to her?’

‘Gas,’ he said, hoping it came out right.

‘Gas poisoning?’

‘Yes.’

Her colleague who had tried to trace the call signalled to her that the attempt had been unsuccessful.

‘And where’s your dad?’

‘Police.’

‘He’s in gaol?’

‘No.’

‘He’s a policeman?’

‘Yes.’

‘And where do you live?’

‘Home.’

‘In which city?’

‘Lisburn.’

‘What’s your name?’

‘Jamie.’

‘And your surname?’

Jamie didn’t know what the word meant, so he didn’t answer.

‘What is your family name?’

Again, Jamie remained silent.

‘Do you know what your full name is?’

‘Jamie.’

‘Jamie what?’

‘Yes.’

‘I mean, when people talk to your dad, what do they say after Mister?’

Jamie didn’t get this. People were talking about all kinds of things after addressing his dad.

The operator sighed in despair, but suddenly she paused.

When Jamie didn’t understand a question or know the answer, he kept quiet. When he answered, his replies were short but coherent. So why had he answered the question ‘Jamie what?’ with ‘Yes’?

‘Sam’, she said to her colleague, ‘could you check whether there is a policeman by the name of Watt stationed in Lisburn?’

On the bright side, his parents were a lot nicer to him than they used to be. But he didn’t understand all the fuss that was being made about him, being called a hero and such. After all, any child in his situation would have done the same, wouldn’t they?

MORE ON AUTISM