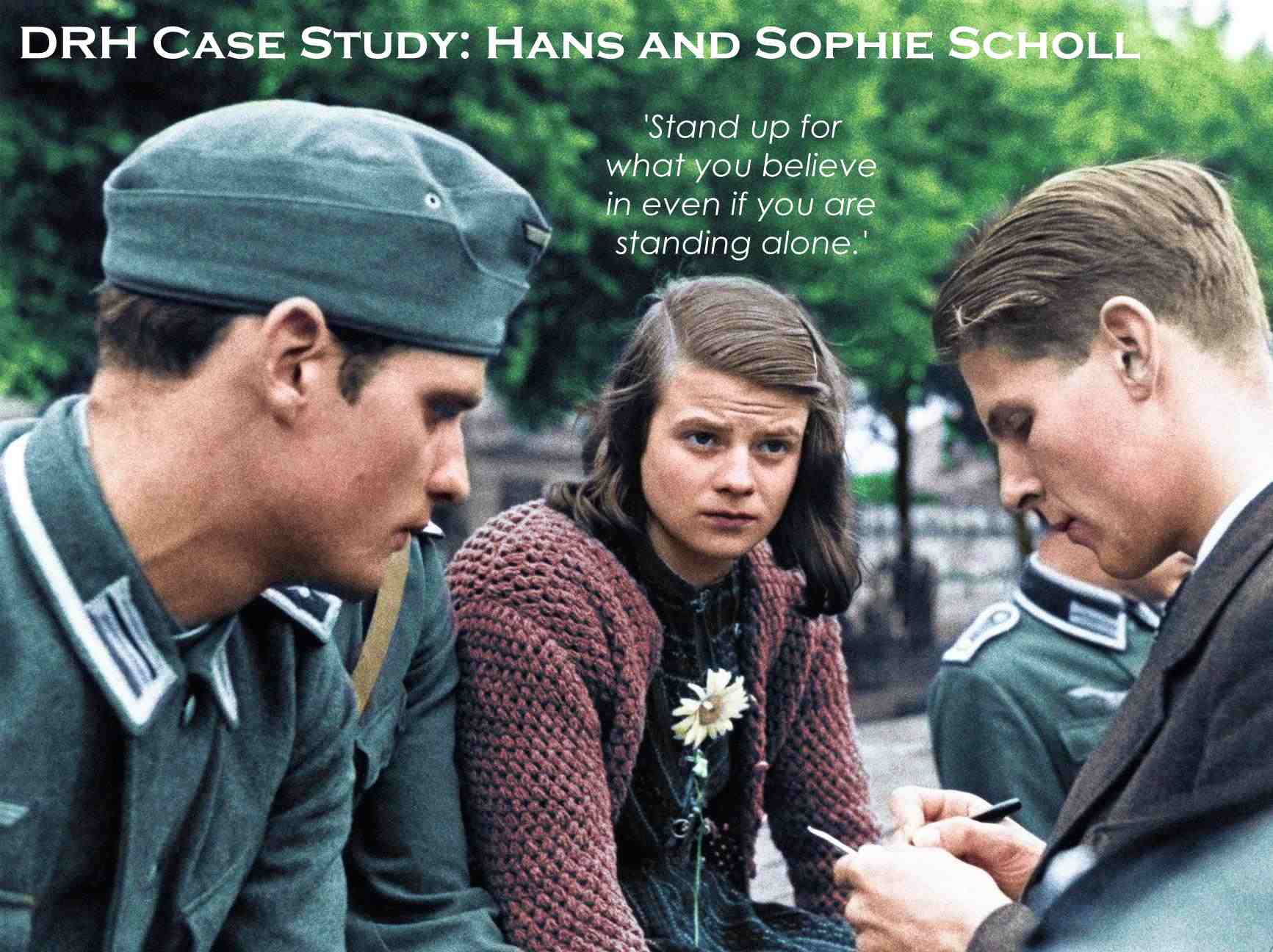

Hans and Sophie Scholl: Conscience and Individuality under Nazism

Hans (born 1918) and Sophie Scholl (born 1921) grew up in a liberal, educated family in southern Germany. Their father, Dr. Robert Scholl, was a political liberal and outspoken opponent of the Nazis, and their mother, Magdalena, was a devout Christian. The siblings' home life encouraged open discussion of ideas and values. Banned books were read at the dinner table and forbidden broadcasts (like the BBC) were listened to in secret. In this atmosphere of free inquiry, the Scholl children - five in all - were taught to question authority and value truth.

By the early 1930s both Hans and Sophie, like many German youths, briefly embraced Nazi organisations. In 1933 they enthusiastically joined the Hitler Youth (Hans) and the League of German Girls (BDM). Their parents had warned against Nazism, so this early involvement was partly a youthful urge to belong and love of country. However, their experiences in these groups quickly led to deep disillusionment. As one scholar notes, Hans and Sophie 'became disillusioned by their experiences in the Hitler Youth and began to oppose virulently every manifestation of Nazism'. In other words, the very collective identity pressures meant to bind them only spurred them to question and rebel.

Moral Awakening and Education

After 1937 the Scholls' path began to diverge sharply from Nazi norms. Hans entered the University of Munich in 1939 to study medicine (while still serving as an army medic). On the front lines and in military hospitals he witnessed terrible suffering. In letters home he confessed his horror at the slaughter, writing 'I don't know how long I can continue to contemplate this slaughter.' His writings of this period show a pronounced sensitivity and clarity of thought about right and wrong. Sophie graduated high school in 1940 and entered the Reichsarbeitsdienst (a state labour service) in 1941. She hated the regimentation. Working on military projects under harsh conditions, Sophie turned inward, reading theology and philosophy (especially Augustine of Hippo) and writing in her diary of a 'hungry' soul longing for peace, autonomy, and an end to the war. Both siblings increasingly questioned the brutality and lies of the Nazi system. Sophie's own doubts grew, and letters and conversations show that both Scholls detested the mindless standardisation of life under Nazism. Even as young adults, they refused to accept the ideological conformity demanded by regime propaganda.

All the while, Hans and Sophie nurtured independence and critical thinking. Before the war, the Scholl home had become a refuge for like-minded friends who felt alienated by Nazi culture. They read banned literature (including works by Jewish and other 'outlawed' authors) and discussed ethics and faith around the dinner table. These discussions - with parents who openly criticised Nazi policies - reinforced the siblings' sense that truth was not defined by the Party. By 1941–42, they were reading forbidden material and writing their own reflections in a handwritten magazine (Windlicht) to maintain 'some form of self-expression beyond the reach of the regime'. In short, both Scholls prioritised personal conscience and intellectual honesty over ideological pressure.

The White Rose Resistance

In Munich in the summer of 1942 Hans and Sophie joined (and soon helped lead) the White Rose, a small group of students and a professor dedicated to nonviolent resistance. By then Hans had befriended other dissident medical students (like Alexander Schmorell and Willi Graf) in his army unit, and Sophie arrived in Munich in May 1942 to study biology and philosophy alongside him. The group quickly began printing anti-Nazi pamphlets and distributing them anonymously. These leaflets denounced the terror of the regime, urged passive resistance to the war, and criticised the Holocaust as it was happening. Sophie read the first leaflets and was so moved that she 'demanded to join the group' - she could no longer 'stay passive'. Together the Scholl siblings and their friends mailed thousands of leaflets across Germany and plastered graffiti calling for freedom.

Their actions showed remarkable moral courage and clarity. On February 18, 1943, Hans and Sophie boldly walked into Munich University, dropped stacks of leaflets onto lecture halls and stairs, and shouted 'Freedom!' - directly challenging the regime's in-group norms. A janitor alerted the Gestapo, and the siblings were arrested on the spot. Days later they were subjected to a show trial. Even then, Sophie Scholl remained unflinching. When asked if she now regretted her actions as crimes against 'the community,' she replied simply: 'I am, now as before, of the opinion that I did the best that I could do for my nation. I therefore do not regret my conduct and will bear the consequences.'. That moral resolve - valuing conscience over compliance - underscores their principled stance. On February 22, 1943, Hans and Sophie (aged 24 and 21) were executed by guillotine for treason.

Psychological Profile: DRH and NSM Perspectives

From the standpoint of the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (DRH), the Scholl siblings exemplify the rare individuals who 'resist social conditioning and retain their individual identities'. Ludwig's theory holds that all children are born with a sense of self, but most are trained into collective identities through pressure to conform. Hans and Sophie bucked this trend. They maintained their inner moral compass even as their peers were collectivised by Nazi ideology. In Ludwig's words, human progress depends on those who resist losing their individuality to groupthink. The Scholls did exactly this: they paid a terrible personal price - ostracism and death - for refusing to subordinate their conscience to the in-group.

The Neurological Spectrum Model (NSM) sheds further light. Ludwig posits a spectrum from the 'Individual' extreme to the 'Social Person' extreme. An Individual (in Ludwig's sense) is someone who 'acts based on their individual judgment alone' and treats others as equals. Conversely, a Social Person is someone who has absorbed group expectations without individual judgment, viewing their own group as superior. The Scholls unmistakably fall at the Individual end. They regarded each person (even an enemy) with human concern rather than group-based hatred. For example, Hans's letters show empathy for all victims of war, and Sophie's indictment answer frames her resistance as service to the nation's true good, not to Hitler's regime. They exemplified Ludwig's description that the Individual 'remains immune to any outside influences' and 'approaches everybody else as an equal human'.

Key traits of the Scholls in NSM terms:

• Independent Conscience: They did not 'just follow orders.' As Ludwig notes, the Individual stands by what they believe is right and 'accepts responsibility' for it. Hans and Sophie repeatedly took personal responsibility for the White Rose activities, insisting they (not others) were responsible for the leaflets. Hans calmly acknowledged their guilt after arrest, and Sophie's trial statement accepted full consequence.

This mirrors the Individual's refusal to cede moral agency to authority.

• Empathy Across Differences: Ludwig's Individual 'cares about the wellbeing of others, regardless of how different these people may be from them'. This fits the Scholls' outlook. Sophie later insisted that even ordinary Germans were victims of Nazism's deceit. The White Rose leaflets speak of common humanity and urge readers (fellow Germans) to defy their leaders to end suffering. Similarly, Ludwig contrasts this with the Social Person who sacrifices individuals for the group (the Nazi motto 'Germany must live even if we die' is cited in Ludwig's writing). The Scholls rejected that view: they saw Germans and non-Germans alike as equals in suffering, not as an 'us vs. them' enemy.

• Intellectual Independence: Both siblings loved ideas and resisted propaganda. Ludwig emphasises that Individuals 'promote the moral values they live by' and speak truth irrespective of group expectations. Hans and Sophie did exactly that. They refused to echo Nazi slogans and instead privately debated theology and philosophy to make sense of the world. In fact, friends recall that in Munich one could outwit party indoctrination by selective study - a strategy Sophie reportedly used. The NCR commentator Paul Shrimpton summarises: they 'asserted intellectual independence' against mindless propaganda. This trait aligns with Ludwig's view that individuals value diversity, encourage children's self-expression, and prize truth over the group's narrative.

• Moral Clarity and Courage: Ludwig explicitly lists progressives, human rights activists, and whistleblowers as typical of the far Individual end - precisely the categories the White Rose fit. Hans and Sophie interpreted their education and faith as mandating resistance. Sophie famously wrote 'Freiheit' ('Freedom') on her indictment the day before execution, embodying the Individual's hope for a better future for everybody. Their actions demonstrate Ludwig's point that those on the individual end value equality and ethical consistency above belonging.

Collective identity, by contrast, can breed blind obedience. Ludwig warns that group-bound thinking 'create[s] a sense of superiority' and can 'lead to ostracising, dehumanisation and even elimination of other groups'. This grim fact underlay the Scholls' courage: they intuitively resisted the dehumanising group mindset that was driving genocide. In facing down a regime that demanded conformity, Hans and Sophie remained faithful to their individual selves.

Summary: In Ludwig's terminology, Hans and Sophie Scholl are prime examples of deindividuation resisters on the 'Individual' end of the neurological spectrum. They maintained their innate sense of self, upheld their personal ethics against collective norms, and acted as if each human life was equal (as Ludwig's Individual does). In doing so, they embodied the advantages of this orientation - intense empathy, clarity, and creative moral reasoning - even as they suffered the disadvantages (ostracism, state violence) predicted by the theory.

Legacy and Context of Resistance

The White Rose siblings paid for their convictions with their lives. Their martyrdom did not halt Nazi atrocities, but it did resonate widely. Abroad, voices like writer Thomas Mann and the Allies used the White Rose pamphlets to rally opinion against Hitler. Back in Germany the regime tried to bury the story; only after the war did Hans and Sophie become national icons. Today the White Rose is synonymous with youthful conscience, and Sophie in particular is memorialised - a BBC poll named her 'Germany's greatest woman' and nearly 200 schools there bear her name.

In the broader context of repressive regimes, Hans and Sophie's example fits a familiar pattern. History offers many who held firm to their individual identity and conscience: from medieval reformers to modern activists. Ludwig's framework would include them with others at the individual end of the spectrum - figures whose independent thinking sparked change. Like Galileo or Mahatma Gandhi (also studied by Ludwig), the Scholls refused to give in to peer pressure or authoritarian commands. In every era, such resisters are few but crucial: Ludwig asserts that human progress depends on 'those who think and act individually'. Hans and Sophie's legacy lies in having done just that. They remind us that even under totalitarianism, the human spirit can maintain moral clarity and equality, standing alone if need be.

In sum, the Scholl siblings' biography - their upbringing, education, friendships, beliefs and ultimate sacrifice - can be read as a case study of deindividuation resistance. They illustrate Ludwig's theses in action. Where Nazi society demanded group loyalty and blind obedience, the Scholls held to their own inner truths. That individualism, likely rooted in their neurological orientation, made them powerful resisters. It also cost them dearly. Their story, however, endures as a testament to the strength of conscience over conformity.

Sources: Historical details are drawn from documented biographies and essays. Psychological analysis uses Ludwig's published DRH/NSM theory.