Early Life and Education (1918–1941)

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in the village of Mvezo in South Africa's Eastern Cape. He was born into the Thembu royal lineage; his father was a counsellor to the Thembu regent, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo. The young Mandela grew up hearing elders' tales of ancestral resistance against colonial rule, which instilled in him a dream 'of making his own contribution to the freedom struggle of his people'. At age 7, he entered primary school where a teacher gave him the English name Nelson, as was custom under British-influenced schooling. His birth name, Rolihlahla, colloquially means 'troublemaker' in Xhosa - a fitting hint of the principled trouble he would stir in later years.

Mandela was an able student. He completed his secondary education at Healdtown, a respected Wesleyan college, and then enrolled at the elite University College of Fort Hare in 1939. There he began a Bachelor of Arts degree. However, in 1940 Mandela was expelled from Fort Hare for joining a student protest against university policies. This early act of campus defiance demonstrated his willingness to stand by his convictions even at personal cost. When he returned home, the regent Jongintaba - disappointed by Mandela's expulsion - threatened to arrange marriages for Mandela and his cousin Justice as a corrective measure. Rather than submit to this traditional authority, the two young men fled their rural home for Johannesburg in 1941. In Johannesburg, Mandela took up odd jobs (including as a mine night-watchman) before meeting lawyer Walter Sisulu, who helped him find clerical work at a law firm. Showing determination to continue his education, Mandela completed his B.A. via correspondence and eventually earned his degree in 1943. That same year, he enrolled in law studies at Wits University in Johannesburg. Though he struggled academically at law school and left Wits without graduating in 1952, these years in Johannesburg were transformative. He was exposed to a vibrant Black South African urban culture and a rising political consciousness.

Theoretical Analysis: Formative Years – Individual vs. Social Orientation

Mandela's formative years already reveal a strong individual-oriented drive in the sense of the Neurological Spectrum Model (NSM). The NSM posits a spectrum from the 'ultimate individual' - one guided by personal judgment and immune to outside pressures - to the 'ultimate social person' who absorbs group expectations and norms unquestioningly. In his youth, Mandela repeatedly chose personal principle over passive conformity. His expulsion from Fort Hare for leading a student strike is an early sign of resistance to authority and group pressure; rather than acquiesce to the college administration (an authority structure), he followed his own moral reasoning. Likewise, fleeing an arranged marriage - defying the expectations of his guardian and tribe - illustrates young Mandela asserting individual choice over traditional collective norms. According to the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (DRH), certain individuals are 'wired to resist systems that demand compliance over authenticity'. In a society structured by strict customs and colonial authority, Mandela's willingness to 'burn out…trying not to explode from the sheer voltage of existence' by saying 'no' to imposed rules is characteristic of a deindividuation resister. Far from a pliant social actor, the young Mandela's choices placed him toward the individual end of the spectrum - a position associated with acting on personal conviction and treating others as equals rather than accepting unequal, traditional hierarchies. Notably, even as a youth he was inspired by stories of resistance (wars against colonisers), suggesting an early identification with those who stand apart from an unjust social order. This set the stage for the individual moral compass that would guide his political life.

Political Awakening and Activism (1940s–1950s)

In Johannesburg in the 1940s, Mandela's political awakening accelerated. He was mentored by figures like Walter Sisulu and joined study groups with activists, exposing him to ideologies of African nationalism, anti-colonialism, and non-racialism. Although politically active as early as 1942, Mandela formally joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1944, at age 26. That year he co-founded the ANC Youth League (ANCYL) alongside Anton Lembede, Oliver Tambo, and others. Mandela and his Youth League colleagues sought to invigorate the ANC, which they felt had been too moderate and elitist. They advocated for mass mobilisation, African self-determination, and a bolder confrontation with apartheid. By 1949, their influence was clear: the ANC adopted the Youth League's Programme of Action, committing to strikes, boycotts, and civil disobedience against unjust laws. This was a decisive shift from petitioning to militant nonviolent resistance, and Mandela was at the forefront of that radicalisation.

In the 1950s, Mandela emerged as a leading activist in the anti-apartheid struggle. In 1952 he was appointed Volunteer-in-Chief of the Defiance Campaign, a coordinated campaign of civil disobedience jointly organised by the ANC and the South African Indian Congress. He travelled the country inspiring volunteers to deliberately break apartheid's pass laws and segregation statutes. That campaign saw over 8,000 arrests, including Mandela's; he was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act and given a suspended prison sentence. Also in 1952, Mandela - by now one of the few Black South Africans with legal training - partnered with Oliver Tambo to open Mandela & Tambo, the country's first Black-owned law firm. The firm defended many Blacks charged under apartheid laws, further pitting Mandela against the system on legal grounds.

As Mandela's profile grew, the regime struck back. He was 'banned' (restricted by government order) for the first time in late 1952, limiting his travel and public speech. Despite such curbs, Mandela worked behind the scenes on the ANC's next vision: the Freedom Charter. In 1955, the Charter - a manifesto of democratic principles compiled from ordinary citizens' demands - was adopted at the Congress of the People in Kliptown. Mandela, though present in spirit, had to watch in secret due to his banning order. The Charter's ideals of a non-racial, egalitarian South Africa would eventually guide Mandela's movement, but at the time it was deemed treasonous by authorities. In 1956, Mandela and 155 other activists of all races were arrested and charged in the infamous Treason Trial. The trial dragged on until 1961, ending with Mandela and all co-accused acquitted. These years tested Mandela's resolve: he juggled a life underground at times, advocacy in court, and personal struggles (his first marriage, to nurse Evelyn Mase, fell apart by 1958 amid the strains of activism). Through the 1950s, Mandela's commitment only deepened as apartheid repression intensified - notably with the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, where police killed 69 unarmed protestors, leading to the banning of the ANC. By 1961, it was clear to Mandela that new tactics were needed for the freedom movement.

Theoretical Analysis: Defying Conformity and Authority in Early Activism

During the 1940s–50s, Mandela's evolution as an activist showcases a balancing act between collective identity and individual moral agency. On one hand, he was building a movement - embracing a collective identity as an African nationalist and ANC leader. On the other hand, Mandela consistently demonstrated independent critical thinking within that collective struggle. According to the NSM, most people operate between individual and social poles; Mandela's behaviour in this era tilts toward the individualist end, even as he worked for group liberation. For example, he pushed the ANC to adopt the bold Programme of Action in 1949, effectively challenging the established norms and cautious strategies of the older ANC leadership. Rather than simply absorbing the traditional moderate approach of his elders, Mandela and his peers introduced a new radical paradigm - a move characteristic of a deindividuation resister who is unwilling to 'move with the current' if it means compromising on justice.

Notably, Mandela's commitment to non-racialism and the Freedom Charter principles also marked an independent stance. Many in the liberation movement were split at the time: some Africanists felt Black South Africans should go it alone. Mandela, however, supported partnering with Indians, Coloureds, and white anti-apartheid allies, as evidenced by the multi-racial makeup of the Congress of the People and Treason Trial defendants. This readiness to transcend a narrow group nationalism for a broader humanist principle - 'I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination', he would later declare - shows an orientation toward universal individual equality over rigid group identity. In NSM terms, he resisted the 'ultimate social person' trap of viewing any one group as superior and demonising others. Instead, even under pressure, he maintained an inclusive vision anchored in his personal sense of justice.

The DRH perspective emphasises those who resist social conditioning and unjust authority as essential drivers of progress. Mandela's activism in this period fits that description well. He did not blindly conform to either the apartheid system or more timid voices within his own movement. Whether by defying apartheid laws in the Defiance Campaign or enduring a marathon Treason Trial without renouncing his beliefs, Mandela exemplified how 'the world is changed by those who think and act individually,' not by those who merely conform. His early leadership thus straddled collective action and personal integrity - a fusion of social purpose with individual conviction that positioned him as a deindividuation resister in a mass movement.

The Turn to Armed Struggle and the Rivonia Trial (1960–1964)

By 1960, the apartheid state's violent clampdowns convinced Mandela that nonviolent protest alone was insufficient. After the Sharpeville massacre and the subsequent banning of the ANC, Mandela went underground. In March 1961, he helped organise an All-In African Conference that resolved to call for a national convention and threaten a general strike if apartheid continued. When the government ignored these appeals and crushed the strike, Mandela embraced a dramatic new course: armed resistance. With the ANC's tacit approval, he co-founded Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK, 'Spear of the Nation') in June 1961 as an independent armed wing of the freedom movement. MK's campaign of sabotage - targeting infrastructure but avoiding loss of life - was launched on December 16, 1961 with coordinated explosions in several cities. Mandela became MK's first commander, operating clandestinely.

In early 1962, Mandela secretly left South Africa (adopting the alias David Motsamayi) to seek military training and international support for the armed struggle. He travelled across Africa and even to London, meeting sympathetic leaders and learning guerrilla tactics. After several months abroad, he slipped back into South Africa. However, on August 5, 1962, Mandela was arrested at a roadblock. He was prosecuted for leaving the country illegally and inciting strikes, and sentenced to five years in prison. While he was serving this sentence, police raided a farm in Rivonia (a Johannesburg suburb) that was being used as a secret MK hideout, seizing documents and arresting many of Mandela's comrades. Although Mandela was already behind bars, he was charged alongside the others in the Rivonia Trial, accused of sabotage and plotting violent revolution. This historic trial began in late 1963.

Facing the possibility of execution, Mandela used the defendant's dock as a pulpit. On April 20, 1964, at the trial's climax, he delivered his famous Speech from the Dock. In this oration, Mandela defiantly affirmed the ideals that guided him, proclaiming in closing: 'I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society… It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.'. These words resonated around the world as a moral indictment of apartheid. A few weeks later, in June 1964, the Rivonia verdict came: Mandela and seven co-accused were convicted. The judge spared them the gallows but sentenced each to life imprisonment. At age 46, Mandela was dispatched to the maximum-security prison on Robben Island, cut off from his people as the anti-apartheid struggle was forced into exile or underground.

Theoretical Analysis: Balancing Personal Convictions and Collective Action

Mandela's decision to adopt armed resistance in the early 1960s highlights a nuanced aspect of his individual-vs-collective dynamic. Up to this point he had been devoted to collective nonviolent action; now he personally concluded that a fundamental change in strategy was morally necessary. This willingness to break with the ANC's long-standing tradition of nonviolence demonstrates Mandela's independent judgment, even as it also bound him to a new collective undertaking (the guerrilla movement). Deindividuation resisters are not contrarians for its own sake, but they will depart from group consensus if their conscience dictates. Mandela's push for armed struggle - a controversial move - exemplifies this: he did not simply yield to the dominant ethos of peaceful resistance espoused by earlier ANC leaders like Albert Luthuli, especially once he felt those methods had been exhausted. In his own justification, 'it was only then, when all other forms of resistance were no longer open to us, that we turned to armed struggle'. This reflects an internal moral calculus overriding both his government's authority and even the prevailing sentiment of some colleagues. In NSM terms, Mandela remained on the 'individual' side of the spectrum – guided by personal moral reasoning rather than uncritical loyalty to any static group doctrine.

During the Rivonia Trial, Mandela's comportment further underscored his identity as a resister of deindividuation. Facing extreme state pressure (and the threat of death), he did not cower or simply fade into the collective of accused. Instead, he asserted his own voice and principles to the world. The content of his courtroom speech is telling: he condemned all forms of racial domination and upheld a universal ideal of equality. By explicitly rejecting both black and white supremacy, he again avoided the trap of an 'ultimate social person' who elevates his own group's interests at all costs. Mandela was, in effect, refusing to become the mirror image of his oppressors. This stance required an independent strength of character, especially when a more vengeful, group-driven rhetoric might have been expected under such dire circumstances. It aligns with DRH's notion that some individuals 'don't trust authority without reason' and won't 'fall in line when something feels wrong'. His famous pledge that the ideal of a free society was one he was prepared to die for encapsulates how firmly his individual conscience guided him, even as he represented a broader movement. Thus, at the culmination of this phase - as Mandela transitioned from activist to prisoner - he epitomised the deindividuation resister: a man unwilling to surrender either to the unjust collective will of the apartheid regime or to unprincipled expedience, standing instead as an individual beacon of moral resolve within the collective struggle.

Robben Island and Resistance in Prison (1964–1990)

Mandela would spend the next 27 years behind bars, the bulk of them on bleak Robben Island in the Atlantic Ocean. In prison, he was isolated from direct involvement in the ANC's guerilla campaign, yet he became a powerful symbol and a quiet strategist for the movement. Life on Robben Island was harsh: Mandela and his fellow political prisoners endured hard labor in a lime quarry, meager rations, and routine abuse from guards. The authorities hoped to break Mandela's spirit, but instead he became the undisputed leader of the prisoners, fostering unity across racial and ideological lines among them. He pushed for better living conditions through persistent advocacy, often treating even the warders with a firm but respectful demeanour that gradually earned him a measure of regard. Tragedy struck during this period - Mandela's mother died in 1968 and his eldest son Thembi died in 1969, yet he was denied permission to attend their funerals. Such personal blows, coupled with years of physical confinement, could have led to embitterment. However, those who knew Mandela in prison recall his remarkable composure, discipline (he pursued studies and encouraged others to educate themselves), and unshakable courtesy even toward those who tormented him.

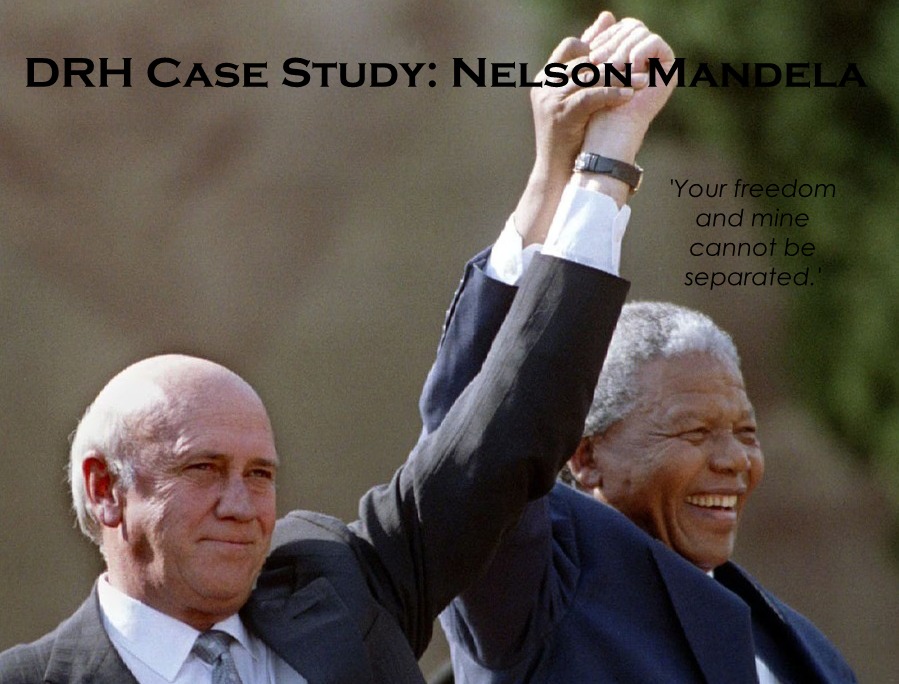

By the 1980s, the apartheid regime, under increasing domestic and international pressure, began to tentatively reach out. Mandela, viewed as a moderate compared to younger militant activists, was separated from his comrades in 1985 and held alone in Pollsmoor Prison. He initiated clandestine dialogue with government ministers from his cell, recognising that a negotiated solution might be possible. Meanwhile, offers were dangled: on at least three occasions Pretoria offered to release Mandela if he would renounce violence and/or accept exile. Mandela flatly rejected all conditional offers. In one famous 1985 response read publicly by his daughter, he wrote, 'What freedom am I being offered while the organization of the people remains banned? … Only free men can negotiate. Prisoners cannot enter into contracts.'. This principled stand - refusing to trade his personal freedom for the integrity of the broader cause - further solidified his stature. In 1988, Mandela was moved to a house prison at Victor Verster (after a bout of tuberculosis), a relative luxury after decades in a cell. Behind the scenes, he continued talks with the government. Finally, seismic change arrived: the new president F.W. de Klerk unbanned the ANC in February 1990, and Nelson Mandela walked free on February 11, 1990 after 27 years of incarceration. The 71-year-old Mandela emerged unbowed and astonishingly free of bitterness, ready to lead his people into negotiations for a new South Africa.

Theoretical Analysis: Preserving Identity and Integrity Under Duress

Mandela's long imprisonment tested the very limits of an individual's capacity to resist deindividuation. Prison by nature is a dehumanising, collectivising environment - inmates are reduced to numbers, subjected to total authority, and pressured to submit. Yet Mandela consistently retained his personal agency and identity throughout those 27 years. In NSM terms, even in an extreme collective coercive setting, he anchored himself on the individual side of the spectrum. His refusal to answer racism with racism or hatred - 'despite terrible provocation, he never answered racism with racism' as noted in his biography - illustrates a steadfast adherence to his own values rather than a reflexive adoption of the enemy's mentality.

A hallmark of deindividuation is the loss of self in a group or system, but Mandela resisted that loss. He maintained dignity by small acts of autonomy (whether secretly writing his memoir, educating younger prisoners, or politely but firmly debating with prison officials). These actions kept his mind free even when his body was confined. The DRH would view Mandela as exemplifying the kind of individual who is 'wired to resist systems that dehumanise, that demand compliance over authenticity'. Indeed, Robben Island's regimen sought to crush authenticity and enforce total compliance; Mandela's very survival as the same principled man after 27 years is evidence of an extraordinary resistance to psychological assimilation. Fellow prisoner Ahmed Kathrada observed how Mandela could even influence some warders to treat prisoners more humanely - a testament to how Mandela's strong sense of self and fairness impacted others rather than the other way around.

Mandela's rejection of conditional release offers also vividly demonstrates his integrity under pressure. A purely self-interested or conformist individual would have leapt at the chance of freedom by yielding to the government's demand that he renounce the armed struggle. Mandela, however, saw that as a betrayal of his cause and identity. He stated plainly, 'I cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when I and you, the people, are not free… Your freedom and mine cannot be separated.'. This response encapsulates the DRH principle that true progress is achieved by those who 'say no' when it truly matters. Mandela's sense of himself as a representative of his people's yearning for freedom became an unbreakable core; he would not allow the regime to define the terms of his existence or co-opt him. In psychological terms, he resisted the brainwashing and identity-stripping effects incarceration can have. Through the lens of NSM, he remained far toward the individualist pole - guided by internal principles rather than external rewards or fears. It is telling that when he was finally released unconditionally, it was on his terms - as a free man negotiating the fate of his country, not as a compromised former prisoner. In sum, Mandela's prison years showcase the ultimate deindividuation resister: one who, even in isolation and adversity, preserved his individual moral compass and emerged prepared to shape society rather than being shaped by a repressive society.

Leadership and Presidency (1990–1999)

Mandela's release in 1990 marked the beginning of South Africa's transition from apartheid to multiracial democracy. After nearly three decades away, Mandela immediately assumed a pivotal leadership role. He astutely guided the ANC in negotiations with President F.W. de Klerk's government, working through the early 1990s to dismantle apartheid laws and set up the country's first free elections. Mandela's personal stature and conciliatory approach were critical in this tense period; he reassured the white minority and international observers even as he pressed firmly for majority rule. In 1991, he was formally elected President of the ANC (succeeding his old friend Oliver Tambo). The negotiation process was arduous - at times punctuated by violence from various factions - but Mandela remained a voice of reason and calm. In 1993, his efforts alongside de Klerk earned them the Nobel Peace Prize jointly, symbolising the reconciliation taking shape.

On April 27, 1994, Nelson Mandela cast his vote in South Africa's first fully democratic election - the first time he had ever voted in his life. The ANC won overwhelmingly, and on May 10, 1994, Mandela was inaugurated as the first Black President of South Africa, at age 75. As President (1994–1999), Mandela faced the colossal task of uniting a deeply divided society. Remarkably, he eschewed vengeance and instead championed forgiveness and inclusion. His administration established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) under Archbishop Desmond Tutu's chairmanship, which exposed the horrors of apartheid-era crimes but emphasised restorative justice over punitive trials. Mandela personally set examples of reconciliation - for instance, in 1995 he donned the green jersey of South Africa's historically white rugby team, the Springboks, at the World Cup final, galvanising a moment of national unity. Such gestures had a profound psychological impact, helping to bridge the chasm between former adversaries.

Mandela's leadership style was consultative and humble. He earned the affectionate nickname 'Tata' (Father) as he often referred to South Africans as his children and prioritised nation-building over partisan politics. He also had the insight to step away from power at the right time. 'True to his promise,' Mandela served only one term and stepped down in 1999, handing over leadership rather than clinging to office. In doing so, he broke the mould of many post-colonial African leaders. By the end of his presidency, South Africa had a new constitution grounded in human rights, and Mandela had solidified his legacy as a peacemaker. In July 1998, on his 80th birthday, the widowed Mandela married Graça Machel (his third marriage) - a personal happiness that accompanied his graceful exit from formal political life.

Theoretical Analysis: A Deindividuation Resister in Power

Mandela's conduct as president further cements his status as a 'deindividuation resister' - perhaps paradoxically, because he did not allow power or the trappings of high office to erode his principles or individual authenticity. Often, when individuals assume leadership, they may become consumed by the identity of their office or party, losing the independence of thought they once had. Mandela did the opposite. He retained the same core values - fairness, inclusivity, humility - that he had developed over a lifetime, rather than adopting an authoritarian or group-superiority mindset despite leading the majority. This aligns with the NSM's ideal of the 'ultimate individual' who, even in a position of authority, 'acts based on their individual judgment alone' and 'regards everybody as an equal (no more and no less)'. Mandela's insistence on treating former enemies as equals - exemplified by his outreach to white citizens and even to figures of the old regime - was a striking illustration of resisting the pull of tribalism. Instead of championing a narrow 'us vs. them' ethos (which many of his own supporters might have understandably felt), he consistently spoke of one South African people, thereby resisting the collective pressure to favour his own group at the expense of reconciliation.

Several key decisions in Mandela's presidency highlight his independent moral reasoning triumphing over any collectivist or populist temptations. Establishing the TRC, for instance, was not an idea universally popular among the victors of the struggle - some wanted retributive justice. Mandela's backing of truth-telling plus forgiveness reflected a deeply personal conviction that healing was better than revenge. It also required him to withstand hardliners in his own movement - a classic behaviour of a deindividuation resister who will not simply conform to a vengeful group sentiment. Likewise, his famous gesture of wearing the Springbok rugby jersey during the 1995 World Cup, cheering for a team once seen as a symbol of white oppression, was a bold act of individual leadership that transcended ingrained group animosities. Many Black South Africans had long vilified that team; Mandela's choice to visibly support it signalled to the nation that it was time to unite. He was effectively modelling the NSM ideal of seeing members of former out-groups as fellow human beings, not eternal enemies. This kind of vision in a leader required resisting the easy path of pandering to one's base. Instead, Mandela followed his own sense of what was right for the country's soul.

Finally, Mandela's voluntary retirement after one term in office speaks volumes about his relationship to power and identity. Rather than being subsumed by the role of 'President' or pressured by his party to continue, he kept his personal principle - that democracy is strengthened by smooth succession - front and centre. In a continent where many leaders clung to power, Mandela's decision to step down was almost radical in its humility. It illustrates that he never let the collective adulation or authority override his inner guide. In DRH terms, he remained one of those individuals 'born to say no' - even saying no to the allure of power and the chorus of those who would have happily kept him in office. His presidency, therefore, was not a story of one man subsumed by high office, but one man using high office to articulate and execute his enduring, personal moral vision. Mandela the President was the same authentic Mandela that entered prison decades prior - proof that he resisted the deindividuation that often comes with political power, and in doing so, left an example of ethical leadership rarely seen.

Later Years and Legacy (2000s–2013)

After leaving the presidency in 1999, Nelson Mandela took on the role of elder statesman and humanitarian. He did not withdraw from public life immediately; instead, he used his global stature to advocate for causes and to guide younger leaders. In the early 2000s, one of Mandela's prominent campaigns was against the HIV/AIDS epidemic devastating South Africa. In this, he again showed independence of mind. At the time, his successor President Thabo Mbeki was mired in denialist controversies about AIDS. Mandela, in contrast, spoke out forcefully for science and urgent action. In 2000 he openly criticised the government's foot-dragging, stating he shared 'the dominant opinion that prevails throughout the world' that HIV causes AIDS and warning that leaders should not flirt with pseudo-scientific theories while millions were dying. Such frank public criticism of his own party's sitting president was virtually unprecedented - a measure of Mandela's willingness to break ranks for a moral imperative.

Mandela's later years also saw him mediating peace in conflict zones (he facilitated talks in Burundi, for example), championing children's rights through his Nelson Mandela Children's Fund, and continuing to preach reconciliation on the world stage. He became a vocal critic of human rights abuses regardless of the quarter. Notably, he did not shy from rebuking those who had been his comrades: he subtly admonished Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe as that country's governance deteriorated, urging African leaders to uphold democratic principles. In retirement, Mandela increasingly devoted time to his family - he had a large extended family and enjoyed being 'Granddad' in his final years - but even his personal milestones were shared with his nation. On his 90th birthday in 2008, frail but smiling, he urged the people to continue fighting poverty and building peace. In his final public appearance, at the 2010 FIFA World Cup in Johannesburg, he was greeted with roaring affection, a living symbol of unity. Mandela passed away on December 5, 2013, at the age of 95. The outpouring of respect from across South Africa and around the globe was immense. In death, as in life, Mandela stood as a towering example of integrity, compassion, and the power of the human spirit to overcome social conditioning.

Theoretical Analysis: Enduring Influence of Individual Moral Leadership

Nelson Mandela's post-presidential life and broader legacy reinforce how he can be seen as a prototype of a deindividuation resister whose impact reverberated far beyond his own person. Even in old age, he continued to challenge groupthink and authority when necessary - take his stance on HIV/AIDS. By the 2000s, Mandela was almost universally revered; he could have easily avoided controversy. Yet when he observed his successor promoting a harmful narrative about AIDS, Mandela spoke out, effectively saying 'this is wrong' despite the political discomfort it caused. This act is the hallmark of the permanent resister: the courage to voice inconvenient truths and uphold objective principles over loyalty to an in-group or deference to power. It underscores that Mandela's internal compass still took precedence over external pressures, aligning with the DRH view that some individuals remain 'resistant to B.S.' throughout life. His status did not make him complacent or a prisoner of popularity; instead, he leveraged it to push society closer to sanity, as DRH might frame it.

Mandela's legacy also invites comparison to other historic figures through the NSM/DRH lens. Like Mahatma Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr., Mandela combined a collective struggle with personal moral authority, often placing him at odds with more extreme elements of his own side. One might also liken him to figures the DRH literature highlights as paradigm resisters - for example, Greta Thunberg in the climate movement or Rosa Parks in the civil rights movement - individuals who refuse to 'fit into a sick system' and instead force the system to make room for those born to say no. Mandela's life affirms the NSM idea that human progress depends largely on those nearer the individual end of the spectrum, who do not simply mirror their society's norms. Under apartheid, most whites accepted or actively enforced racist norms; Mandela and a few others rebelled. Even within the oppressed, many adjusted to survival under tyranny; Mandela stood out by imagining a fundamentally different order and holding to that vision. He retained a strong sense of self that transcended the identities imposed on him (whether 'prisoner,' 'freedom fighter,' or 'President'). In doing so, he embodied what Frank L. Ludwig described in the Neurological Spectrum Model: the rare person who, 'immune to outside influences,' treats every human as equal and does not elevate his own group at the expense of others.

In conclusion, across the many chapters of his life - from village boy to revolutionary to statesman - Nelson Mandela exemplified a consistent thread of individual moral agency resisting unjust collective pressures. He evolved and matured, certainly: learning from failures, widening his circle of empathy, and refining his strategies. But that evolution largely moved him further toward the individualist pole in service of universal ideals. If as a young man he had any doubts about challenging authority, those fell away as he repeatedly chose conscience over convenience. By his later years, he was a figure almost synonymous with moral integrity - arguably the ultimate 'resister' of deindividuation, who never lost himself in anger, never lost sight of the humanity in others, and never abandoned his principles to expediency. As his official biography aptly states, 'Nelson Mandela never wavered in his devotion to democracy, equality and learning. Despite terrible provocation, he never answered racism with racism.'. In the framework of NSM and DRH, this is the legacy of a man firmly on the side of the Individual: a singular leader whose steadfast personal ethics transformed his society and inspired the world.

Sources:

Nelson Mandela Foundation – Biography of Nelson Mandela

Frank L. Ludwig – Neurological Spectrum Model (NSM)

Frank L. Ludwig – Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (DRH)

Prison Photography – Mandela's 1985 Letter Rejecting Conditional Release

The Guardian – Mandela's criticism of Mbeki's AIDS stance