Martin Luther King Jr stands as one of the 20th century's most influential figures, renowned for his leadership in the American civil rights movement. This comprehensive biography examines King's life and legacy through the combined lens of the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (DRH) and the Neurological Spectrum Model (NSM). These frameworks, as outlined in the provided documents, explore how individuals maintain personal identity and moral judgment in the face of intense social pressure. According to the NSM, human personalities range between two poles: the Individual, who acts on independent judgment and remains immune to outside influence, and the Social Person, who subsumes personal identity into collective norms. The DRH similarly posits that while most people undergo deindividuation (losing individuality to group identities), rare individuals resist social conditioning and retain their authentic selves despite ostracism. Martin Luther King Jr can be seen as a prime example of such an individual - someone who prioritised personal conscience over group conformity, refused to 'just follow orders', and challenged unjust collective dogmas at great personal risk.

Martin Luther King's entire life - from his formative years in the segregated South, through his rise as a civil rights leader, to his courageous stands against racism, militarism, and poverty - exemplified the DRH resister traits and the individual end of the neurological spectrum. He consistently acted according to higher moral laws and universal principles, even when this meant going against prevailing social norms, the expectations of both friend and foe, and even laws he deemed unjust. In doing so, King retained a strong sense of individual identity and moral agency, rather than conforming to the collective identity pressures of his time (whether the culture of segregation in the South or the nationalist fervour during the Vietnam War). The chapters that follow chronicle Martin Luther King Jr's life in detail - his childhood, education, ministry, activism, trials, and ultimate sacrifice - highlighting at each stage how his thoughts, speeches, and actions reflect the individual mindset resisting deindividuation. We will see how King's unwavering commitment to justice, truth, and equality caused him to challenge dominant group ideologies (white supremacy, violent militarism, shallow patriotism) in favour of a moral universalism that embraced all people as equals. In parallel, we will interpret his struggles - from disagreements with more timid allies to harassment by the FBI - as the price he paid for 'not fitting in' to what society found comfortable or 'normal'. As the DRH asserts, those who drive human progress are often those willing to stand outside the norm and be labelled 'troublemakers' for the sake of what is right. Martin Luther King Jr's journey vividly illustrates this dynamic.

Before diving into the narrative of King's life, it is helpful to outline a few key concepts from the DRH and NSM frameworks that will inform our analysis:

• Individual vs. Social Person: In the NSM, the Individual relies on personal conscience and reason, treating each person as an equal individual, whereas the Social Person defines themselves by group membership (race, nation, religion, etc.) and adopts the group's prejudices and commands without question. An Individual 'stands up for what they believe is right and just, regardless of their affiliation', never 'just follow[ing] orders' or the crowd against their own moral judgment. King's life will show countless examples of this Individual orientation. By contrast, the Social Person fears dissent and clings to hierarchy and us-vs-them thinking, justifying even immoral acts if they serve the group's dominance. King spent his career fighting exactly such blind conformity and group prejudice in society.

• Deindividuation Resisters: The DRH suggests most people, in order to be accepted, undergo social conditioning that replaces their individual identity with collective identities (nationality, race, etc.), but a small minority resist this deindividuation process. These resisters maintain independent thought and integrity, at the cost of being deemed 'not normal' or facing social punishment. They are often accused of being too extreme or not fitting the norm - yet, as the DRH notes, 'progress, by definition, happens outside the norm'. Martin Luther King Jr was frequently castigated by opponents (and even moderates) as an agitator, extremist, or troublemaker, reflecting this phenomenon. Yet his steadfast adherence to principle over popularity propelled social progress.

• Moral Independence and Conscience: A core trait of deindividuation resisters is that they follow their own conscience rather than the crowd. They feel, as King himself once said, that 'noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good.' King believed no moral person could ever adjust to an unjust system of oppression; instead, one must resist it. This outlook, inspired by thinkers like Henry David Thoreau and exemplified by King's hero Mahatma Gandhi, undergirded King's philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience - the deliberate, principled violation of unjust laws. We will see how King developed this philosophy during his education and put it into practice throughout his campaigns.

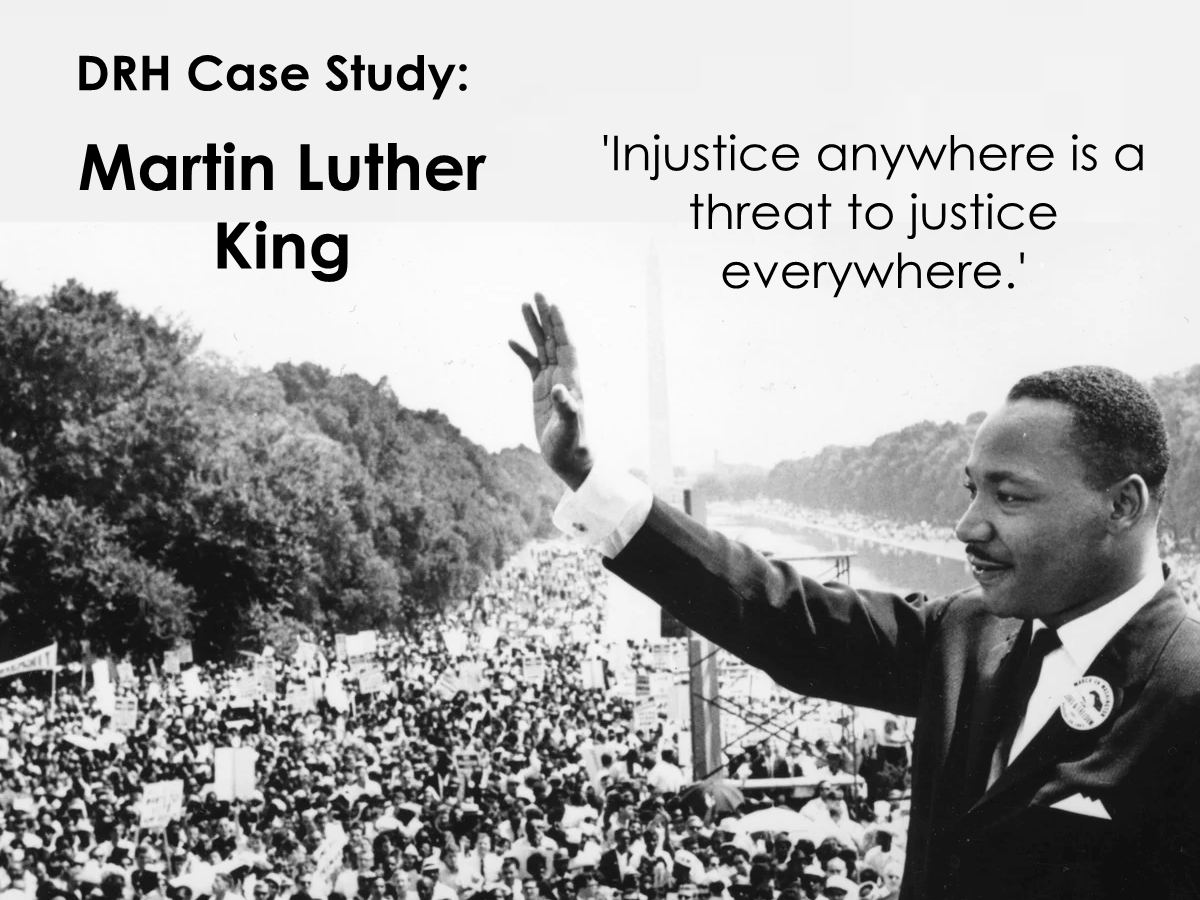

• Empathy and Universalism: Unlike the Social Person who only cares about in-group welfare (what DRH calls nosocentrism, group-cantered concern), King's perspective was strikingly universal. In NSM terms, he identified as an individual first and foremost, enabling him to empathise with all humans as such, regardless of group differences. He preached that 'injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere', demanding concern for people of all races and nations. This broad empathy led him not only to champion Black Americans' rights, but also to speak against poverty and the suffering of Vietnamese peasants bombed by his own government. Such expansive empathy is characteristic of the individual end of the spectrum, which 'cares about the wellbeing of others, regardless of how different these people may be', in contrast to the social person who only feels compassion for their own tribe. King's concept of a 'Beloved Community' of mankind and his refusal to dehumanise even his oppressors reflect this Individual mindset.

With these themes in mind, let us turn to the story of Martin Luther King Jr - tracing his growth from a precocious child in the Jim Crow South into a Baptist minister and then a world-changing activist. Along the way, we will highlight how at each juncture King 'saw the world as it is' rather than as the prejudiced society around him perceived it, and how he continually resisted pressures to conform to injustice. King's life narrative is not only a history of pivotal events in the civil rights movement, but also a case study in one man's extraordinary capacity to retain his individual identity and moral compass amid the strongest currents of collective identity and social conformity.

Chapter 1: Early Life - Foundations of an Independent Mind (1929-1948)

Martin Luther King Jr was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, into a family and community steeped in the African-American Baptist church and the legacy of racial segregation. He entered the world as Michael King Jr, named after his father, Michael King Sr, a Baptist minister. In 1934, after King Sr visited Germany and became inspired by Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther, he changed both his own and his five-year-old son's names - thus Michael Jr became Martin Luther King Jr. King Jr was the second of three children (between an older sister, Christine, and younger brother, Alfred Daniel). He grew up in Atlanta's Sweet Auburn neighbourhood, a thriving Black community. His father, later known as Martin Luther King Sr or 'Daddy King', was pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, and his mother Alberta Williams King was a former schoolteacher. The family was comfortable by the standards of the day - King Jr often said he 'never had to do without food or necessities' - but they were far from insulated from the harsh realities of segregation.

King's childhood home was a nurturing environment that instilled in him confidence, faith, and a sense of self-worth. His parents were deliberate in teaching him that the racist system of segregation was wrong - a man-made social evil, not a natural order. “She made it clear that she opposed this system and that I must never allow it to make me feel inferior', King said of his mother's guidance, recalling how she explained the signs saying 'White' and “Colored” and the other injustices of Jim Crow to him even as a young boy. Both his mother and father stressed that he was 'as good as anyone', countering the pervasive societal message of Black inferiority. This loving affirmation at home was crucial. As the DRH would predict, King's strong individual identity was fostered early on by caregivers who refused to collectively condition him into passivity or self-hate. Alberta Williams King, despite her gentle demeanour, quietly resisted segregation in her own way - she 'never complacently adjusted herself' to that system, and she passed that spirit to her son. In NSM terms, the young Martin was raised to identify as an individual with inherent dignity, not to internalise the subservient role that the “social person” identity for Black people in the South would dictate.

Daddy King was an even more forceful model of resistance. King Jr described his father as having 'an intense and fearless personality' and a strict ethical code. Martin Sr had grown up the son of a sharecropper in rural Georgia and had experienced and witnessed racial violence and humiliation firsthand. Those early experiences kindled in him a lifelong refusal to accept disrespect. King Jr remembered that his father would stand up to white people who mistreated him - a risky act in the early 20th-century Deep South. 'He never hesitates to tell the truth and speak his mind, however cutting it may be', King Jr said of his father, noting that even those who disliked Daddy King's boldness had to admit he was sincere. One telling incident occurred when King Jr was a small boy accompanying his father to a downtown Atlanta shoe store. They sat in the front section, which by custom was reserved for white customers. A clerk told them to move to the back. 'We'll either buy shoes sitting here or we won't buy shoes at all', Daddy King retorted. He then took Martin Jr's hand and walked out, furious at the insult. Martin Jr later recalled this as the first time he saw his father so angry, and it left an indelible impression: 'That experience revealed to me at a very early age that my father had not adjusted to the system… he muttered, "I don't care how long I have to live with this system, I will never accept it."'. Young Martin learned that one does not have to acquiesce to evil; one can resist, even if it means inconvenience or confrontation. In DRH terms, Daddy King was modelling the stance of a deindividuation resister, someone unwilling to surrender his dignity to the collective rules of white supremacy, and this profoundly shaped Martin Jr's conscience.

Despite this familial strength, Martin Luther King Jr's first-hand encounters with racism in childhood were jolting and formative. Perhaps the most heartbreaking lesson came at age six. King had befriended a white boy whose father owned a store across the street from the King home; the two had played together innocently for years. But when school started (with the boys in segregated first grades), the white child's father forbade him from continuing the friendship. One day the boy informed young Martin that he could no longer play with him 'because we are white and you are coloured'. King was stunned. 'I never will forget what a great shock that was to me', he later wrote. That evening, Martin's parents had to explain to him the reality of race in America. It was a bitter introduction. The injustice felt personal and confusing to the child. King recalled that upon learning how unjustly Black people were treated, 'from that moment on I was determined to hate every white person'. His young heart burned with anger. However, his parents - in line with their Christian faith - counselled him not to hate individuals, even as they validated his sense of injustice. They taught him that 'it was his duty as a Christian to love [the white man]', even though whites, by supporting segregation, were doing wrong. Martin struggled with this moral instruction. 'How can I love a race of people who hate me?' he questioned. It was not an easy lesson, and King admitted that as a boy he carried a latent resentment for years. This inner conflict - between righteous anger at injustice and the ethic of love - would later emerge in King's sermons and writings. It is also a classic example of what the DRH describes as the 'inner struggle between individual judgment and external pressure' that many principled people face. In King's case, his individual judgment rightly recognised the evil of racism and wanted to reject those who perpetuated it, while his religious socialisation (external pressure of a moral community) urged him toward forgiveness and love. Remarkably, King managed to harmonise these impulses by loving persons but hating systems of oppression - a nuanced stance that guided his activism.

By adolescence, Martin Luther King Jr had developed a strong sense of justice and personal dignity that stood at odds with the submissive role black people were expected to play. He keenly felt the daily injustices of segregation and quietly made personal resolutions to resist them. He later wrote of riding segregated buses to school in Atlanta: 'I had to sit in the back of the bus, and every time I got on... I left my mind up on the front seat. And I said to myself, "One of these days, I'm going to put my body up there where my mind is."' This vivid anecdote shows King's independent mindset as a teenager - physically he had to comply with the unjust rule, but mentally he refused to accept its legitimacy. Such resolve is characteristic of an individual on the neurological spectrum: even when outwardly constrained, he maintained an inner freedom of conscience that no social norm could erase. At age 14, King had an early opportunity to act on his beliefs. In 1944, he won an oratorical contest in Georgia with a passionate speech about the Constitution and racial justice. Travelling back to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to give up their seats to newly boarding white passengers. Initially Martin refused, frozen in defiance. The driver shouted and cursed until King's teacher implored him to obey for safety's sake. Reluctantly, they stood for the 90-mile ride home. 'That night will never leave my memory. It was the angriest I have ever been in my life', King reflected. This incident - a humiliating injustice right after he had spoken about freedom - further solidified his determination to fight segregation. It also foreshadowed his philosophy that no one should 'patiently adjust' to wrong. The seed of civil disobedience was taking root in him; as he would later echo Thoreau's idea, 'evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice'. King's teenage experiences provided fuel for his emerging moral mission and confirmed his instinct to resist rather than conform.

Academically, Martin was precocious. He 'always had a desire to work', and was an excellent student, skipping two grades in high school. At the tender age of 15, he enrolled in Atlanta's Morehouse College in 1944, one of the nation's leading historically black colleges. There he was mentored by the college president, Dr Benjamin E Mays, a renowned theologian and advocate for racial equality. Under Mays' influence, King's religious faith developed a social justice orientation. However, in these years King also questioned and explored. In a reflection called An Autobiography of Religious Development, he admitted that as an adolescent he had been sceptical of emotional religion and had even concerned his family by initially refusing to make a profession of faith at around age 13. This intellectual independence in matters of religion was another sign of an individual thinker unwilling to simply inherit beliefs without scrutiny. By the time he graduated Morehouse at age 19 in 1948, King had resolved to enter the ministry like his father, but with an eye toward using the church as an instrument for social change.

To further his religious training, King attended Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania from 1948 to 1951. It was at Crozer, a predominantly white, Northern seminary, that King was exposed to a world of ideas that would shape his philosophy. He read voraciously - theology, philosophy, history - and grappled with concepts of just and unjust laws. Most pivotally, King encountered the concept of civil disobedience through Henry David Thoreau's essay On Civil Disobedience. As King later wrote: 'During my student days I read Henry David Thoreau's essay ... I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance. Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so deeply moved that I reread the work several times.' Thoreau's bold stance that one must break unjust laws resonated strongly with King's own childhood resolve not to accept racial injustice. King became convinced, as he phrased it, that 'noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good'. This principle - that one must obey a higher moral law rather than unjust human laws - would underlie King's leadership in the civil rights movement. It aligns perfectly with the NSM Individual's trait of not blindly obeying authority but instead standing up for what is right regardless of orders or majority opinion. King absorbed other intellectual influences at Crozer as well: he studied the Social Gospel theology of Walter Rauschenbusch, Reinhold Niebuhr's views on power and sin, and the example of Christian activists. He also learned about Mahatma Gandhi's use of nonviolent resistance against British colonial rule in India. Gandhi's success using satyagraha (soul force) to achieve social change through mass civil disobedience deeply inspired King. Later, King would explicitly acknowledge Gandhi as 'the guiding light' for the civil rights movement's strategy, and he even travelled to India to learn firsthand (in 1959, as we shall see). At Crozer, King excelled - he graduated at the top of his class in 1951 and was elected student body president, indicating that even among peers he had a charismatic influence. Yet his independence was evident: he refused to drink alcohol, kept a scholarly demeanour, and won the respect of professors for his insight and oratorical skills.

In 1951, Martin Luther King Jr began doctoral studies in Systematic Theology at Boston University. Moving to the bustling, relatively integrated city of Boston was a new experience for the 22-year-old Georgian. There he further broadened his perspective and also found love. He met Coretta Scott, a bright and socially conscious young woman studying music at the New England Conservatory. Coretta, like Martin, hailed from Alabama and was passionate about civil rights. The two married in June 1953. Coretta Scott King would become a steadfast partner in Martin's life and work, sharing his ideals and sacrifices. King's years in Boston (1951–1955) completed his formal education. He earned his PhD at age 25, writing a dissertation on theological influences (though later it was discovered parts were plagiarised, a youthful indiscretion for which Boston University eventually issued a clarification). More importantly, Boston exposed King to a milieu of people of different races interacting more freely, which reinforced his belief that integration was both possible and beneficial. King also honed his concept of the kind of minister he wanted to be: not just a preacher of sermons, but a leader in the community to challenge social evils. He was now equipped with a deep intellectual understanding of ethics, justice, and the Christian tradition of prophetic ministry. The stage was set for him to put theory into practice.

In 1954, King was called to his first full-time pastorate at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. Montgomery was a mid-sised Deep South city, rigidly segregated. At 25, with a young wife and a newborn baby (their first child, Yolanda, was born in late 1955), Dr King returned to the South. He could have chosen an academic or northern ministry career, but instead he stepped right into the lion's den of Southern racism, armed with his faith and ideas. King's arrival in Montgomery would prove historic, for he soon found himself at the forefront of one of the first great battles of the civil rights movement - the struggle to desegregate the city's buses. As we turn to the next chapter, we will see how the philosophy and character forged in King's early years enabled him, when an unexpected moment of leadership came, to respond with exceptional moral courage. He would demonstrate the truth of the DRH insight that 'human progress is the result of individuals who don't go with the crowd [and] who don't "just follow orders"' - individuals exactly like the young Martin Luther King Jr ready to defy the status quo for the greater good.

Chapter 2: Montgomery and the Birth of a Movement (1955-1956)

Martin Luther King Jr had been settled only a year at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery when history literally came knocking. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a Black seamstress active in the NAACP, was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger. Parks' quiet act of defiance was the spark that ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Black community of Montgomery had long resented the mistreatment of Black riders (who paid full fare but were often forced to stand or were kicked off if whites needed seats). Local activists, especially the Women's Political Council led by Jo Ann Robinson, had been waiting for a test case. With Parks' arrest, they mobilised quickly, circulating thousands of leaflets calling for a one-day bus boycott on December 5, 1955.

That one-day protest was so successful - the buses rode nearly empty of Black passengers - that community leaders decided to extend the boycott indefinitely until demands for fair treatment were met. On the evening of December 5, Black citizens packed the Holt Street Baptist Church to discuss the next steps. There, they formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to oversee the boycott, and somewhat to his own surprise, the relatively new pastor Dr King was elected president of the MIA. At 26 years old, King suddenly found himself the primary spokesman and leader of a citywide protest. Why was King chosen? Partly because he was new in town and had no enemies; partly because he was well-educated and eloquent; and perhaps providentially, because others sensed his unique combination of resolve and calm. In taking on this mantle, King would soon exhibit all the hallmarks of a DRH-style resister: an unwavering moral stance, personal courage under fire, and the ability to inspire others to overcome their fears and act according to conscience rather than compliance.

King's opening address at that mass meeting on December 5 set the tone. He preached that the protest was not merely over a bus seat but over justice and human dignity. 'If we are wrong, justice is wrong', he proclaimed, 'and we are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs down like water.' He urged nonviolence and dignity, but also determination – 'There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled by oppression', he said (echoing his own long-held sentiment of being angry and unwilling to adjust to injustice). This speech marked Martin Luther King Jr's emergence onto the national stage. The boycott continued the next day, and the next, as an awe-inspiring demonstration of collective discipline: virtually all of Montgomery's 50,000 Black residents refused to ride the public buses. Instead, they walked, carpooled in an elaborate volunteer system, or found other means. This was a powerful example of a community withdrawing its cooperation from an evil system, exactly as King's studies (Thoreau, Gandhi) had taught him. For King, it must have been a validating moment - seeing theory put into practice and individual consciences uniting to resist injustice collectively. In NSM terms, while each participant was part of a group action, the core motivation was an individual one: people were acting from personal conviction that the segregated system was wrong, rather than mindlessly following social rules. King's leadership helped frame it this way, constantly reminding participants that their higher loyalty was to justice, not to Alabama's segregation laws.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted 381 days and tested King's resolve mightily. Very soon after it began, the white power structure struck back. King and other MIA leaders were threatened, arrested on trumped-up charges, and subjected to legal harassment (King was arrested for the first time in his life on January 26, 1956, for driving 30 mph in a 25 mph zone - a petty intimidation tactic). The most frightening retaliation came on the night of January 30, 1956: Martin Luther King's home was bombed while he was speaking at a mass meeting. His wife Coretta and their infant daughter Yolanda were inside but thankfully uninjured. When King rushed home, he found an angry crowd of Black neighbours gathered, some armed with bats and knives, ready to confront the white authorities who were present. In that moment, King faced a crucial test of his philosophy. He mounted the wrecked porch of his house and urged everyone to put down their weapons and go home peacefully. 'We must meet hate with love', he told the crowd, declaring that he did not want revenge or violence. This incredible scene - a young man who had just narrowly escaped harm to his family, appealing for nonviolence to an enraged crowd - cemented King's position as a moral leader. It also vividly demonstrated one of the DRH/Individual traits: refusal to justify violence even when provoked. King's stance confounded the usual pattern of group behaviour: normally, one group retaliates when attacked by another. But King, guided by deep personal conviction that violence was wrong (and tactically counterproductive), resisted the collective impulse for vengeance. This is the Individual pole in action, prioritising moral principle over group passion. As King later wrote, 'At the centre of nonviolence stands the principle of love.' His ability to carry the crowd with him - persuading them to follow higher moral law rather than the law of retaliation - was a triumph of conscientious leadership.

King's personal faith was also intensely fortified during this period. He often recounted a midnight experience in January 1956, after a particularly threatening phone call, when he sat at his kitchen table on the verge of despair. He prayed aloud for guidance and felt a profound inner peace, as if God spoke to him saying, 'Stand up for righteousness, I will be with you.' This epiphany gave him the strength to continue in the face of fear. King needed such strength, because the boycott took a toll. White opponents attempted to break the protest through legal manoeuvres - in February 1956, King and over 80 others were indicted for conspiring to boycott (using an old law). King was convicted and fined; he chose jail briefly, making a principled point. Through it all, King maintained a calm, unyielding demeanour. Observers marvelled at how this young minister, with constant death threats hanging over him, could still preach hope and not bitterness. The boycott ultimately succeeded. In November 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a lower court's ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional. On December 21, 1956, King and other Black Montgomery residents boarded integrated buses for the first time. It was a moment of victory - and a new beginning. King's leadership in Montgomery had proven the effectiveness of collective nonviolent resistance, and it had made him a national figure. Time magazine ran a cover story on King in 1957, introducing him to a wider audience as a rising civil rights leader. King's name became synonymous with the struggle for Black freedom, and his emphasis on love and nonviolence offered a new paradigm for that struggle.

Analysing the Montgomery chapter through our theoretical lens, we can see that King's role epitomised the deindividuation resister. He galvanised people to break from habitual conformity - in this case, the habit of accepting second-class treatment - and instead to assert their individual and collective dignity. The risk was enormous: by defying Jim Crow laws, Montgomery's Black citizens risked jobs, physical safety, even their lives. Many likely felt fear and the pull of social conditioning telling them not to make waves. But King appealed to something higher in them, effectively saying: You are individuals of worth; don't yield your self-respect by going along with evil. This aligns with the DRH idea that some individuals (and, under their leadership, even groups) can resist the social conditioning that says 'know your place'. Instead of succumbing to what the majority (the white authorities) defined as normal, they created a new norm based on justice. It is instructive that the white power structure, unable to sway King and the protestors through fear, resorted to trying to label and discredit them. King was accused of being an 'outside agitator', a troublemaker, and later in the struggle, of being a communist. These are classic tactics used against deindividuation resisters - pathologise the person who won't conform. The FBI, as we shall explore in a later chapter, would go to extreme lengths to smear King as 'abnormal' or 'evil' in order to undermine his influence. But at this point in 1956, King had passed through the crucible. His individual-cantered leadership had prevailed over social pressure in Montgomery, and it laid a template for confrontations to come.

One more point: The Montgomery Bus Boycott also demonstrated King's emerging ability to balance individual resolve with collective action. While the NSM Individual ordinarily operates from personal conscience, there is strength when many individuals choose together to follow conscience. King helped transform the Black community's shared frustrations into unified, principled action - effectively forging an adaptive collective identity around justice and nonviolence rather than around hate or blind group loyalty. In DRH terms, while most collective identities rely on conformity and 'following orders', the movement King led encouraged critical thought and personal responsibility. Participants were constantly urged to behave morally, not to taunt or attack others, and to hold themselves to a standard of love. Each person who walked instead of rode was making an individual moral choice that added to the group outcome. This formula - mass nonviolent protest sustained by individual commitment - would become the hallmark of King's campaigns.

By the end of 1956, Dr. King had emerged from Montgomery as a tested leader. But he also knew Montgomery was just the opening chapter in a much larger struggle. Recognising the need to spread the nonviolent resistance movement across the South, King and other ministers formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in January 1957, with King as its first president. SCLC aimed to coordinate civil rights activities and 'to redeem the soul of America' through nonviolence. King was now devoting himself full-time to the cause, travelling and speaking widely. In May 1957, he delivered his first national address, the Give Us the Ballot speech, at the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington, D.C., calling for voting rights for African Americans. The Montgomery experience had refined King's message and proved the power of moral pressure.

However, King was also about to face new challenges that would test both his ideals and his personal limits. These included violent resistance from white supremacists (he narrowly survived a stabbing in 1958), frustrating defeats (as in Albany, Georgia), and the psychological strain of constant danger. In the next chapter, we will follow King through the expanding civil rights movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s, as he leads campaigns in city after city. We will see how he navigates internal tensions within the movement and mounting opposition from without. Through it all, we will observe King's steadfast adherence to the core principle that one must follow one's conscience above all. As the DRH notes, 'People who resist social conditioning are often described as "not normal"... The fact is that many issues are actually black and white'. King unflinchingly framed segregation, for example, as a black and white moral issue – 'outright evil', much as he viewed racism as a clear sin (just as Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner had treated slavery as black-and-white wrong, in an example the DRH cites). This clarity of moral vision, uncommon in a society prone to rationalising injustice, kept King and his followers on course even when others wavered.

Chapter 3: Confrontation and Principle - The Expanding Struggle (1957-1963)

Fresh off the victory of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Dr. King in 1957 co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to carry forward the momentum. SCLC was a coalition of Black ministers and community leaders across the South, aimed at nonviolent direct action to challenge segregation. King was chosen as its president, an acknowledgment of his moral leadership. Over the next several years, SCLC and King engaged in campaigns in various cities. These years were a learning period; not every campaign succeeded. But King's reputation grew, as did the resistance against the status quo. Through it all, we see King repeatedly standing at the intersection of clashing forces - radical vs. moderate, violent vs. nonviolent, federal authority vs. states' rights – and urging the path dictated by justice and love.

One of the first major campaigns was in Albany, Georgia (1961–1962). Unlike Montgomery, which focused on buses, Albany's movement (led by local activist Dr. William Anderson) sought to tackle segregation across the city: buses, libraries, lunch counters, and more. King and SCLC joined to assist. However, Albany's police chief, Laurie Pritchett, had studied King's tactics. Pritchett ordered officers to arrest protestors nonviolently and disperse them to jails in a wide area, preventing the spectacle of overcrowded jails or brutality that often generated public sympathy. King was jailed in Albany during December 1961 and again in mid-1962. Ultimately, Albany did not yield dramatic desegregation results at the time. King considered Albany a setback because it lacked a clear single goal and the opponent was cunningly nonviolent in repression. King reflected with honesty that he had perhaps erred tactically. This willingness to reflect and adapt is another individual trait - critical self-examination rather than denial. Many in the collective mindset might rationalise or blame others for failure, but King openly learned from mistakes. It taught him that future campaigns needed narrower targets and that media and national attention were crucial leverage.

Despite Albany's frustrations, King's stature kept rising. In 1962, he was firmly in the public eye, and with that came increased scrutiny and backlash. By now, the FBI under J Edgar Hoover had begun surveillance, acting on Hoover's conviction that King's movement could be influenced by Communists. The white power structure, especially in the South, felt threatened by the success of nonviolent protests. King was the visible symbol, and thus he drew the brunt of praise as well as calculated hostility. Hoover's FBI agents bugged King's phones and hotels, compiling information - including evidence of King's personal flaws such as alleged extramarital liaisons - which they would later weaponise. This harassment was, in essence, an attempt to force King back into line - to neutralise the extraordinary influence of this deindividuation resister. True to form, King remained undeterred.

By 1963, the civil rights struggle hit a dramatic crescendo in Birmingham, Alabama, a city known as 'Bombingham' for its frequent Klan violence. The Birmingham Campaign was the most strategically orchestrated effort by SCLC. Project C (for 'Confrontation') aimed to end segregation in Birmingham through economic pressure and civil disobedience. The campaign began in April 1963 with sit-ins and marches. Birmingham's Public Safety Commissioner, Eugene 'Bull' Connor, was a notoriously hot-tempered segregationist - the antithesis of Pritchett's cool strategy. Soon King made the fateful decision to defy a court injunction against marching, fully aware he would be arrested. On April 12, 1963 (Good Friday), King was jailed along with many others. It was during his week-long imprisonment that King produced one of the most significant documents of the movement – the Letter from Birmingham Jail.

This letter was King's reply to a statement by white moderate clergymen who had criticised the protests as 'untimely' and extremist. Deprived of freedom, writing on scraps of paper in the margins of newspapers, King eloquently laid out the moral reasoning behind civil disobedience. He argued that there are just and unjust laws, and 'one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws'. This echoes the exact principle he embraced from Thoreau and Augustine - that individual conscience supersedes man's unjust rules. King's letter systematically dismantled the moderates' plea for patience. Perhaps the sharpest critique in it was aimed at the very mindset of the 'white moderate'. King wrote: 'I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate… who is more devoted to "order" than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.' He lamented that these so-called well-intentioned people 'constantly say: "I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action"' and who paternalistically urge Black people to wait for a 'more convenient season'. This passage was essentially calling out the Social Person mentality prevalent in society: the prioritisation of conformist order and keeping things comfortable for the in-group over the urgent demands of morality. King boldly stated that 'shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.'

In NSM terms, King was castigating those who, because of group allegiances or fear of change, could not embrace needed justice. The white moderate valued the collective status quo (social cohesion among whites, absence of conflict) above the fundamental rights of individuals (Black people's freedom). King was imploring them to adopt an individual's perspective - to see African Americans as fellow individuals deserving equal treatment, not as a disturbing 'other' threatening their way of life. The Letter from Birmingham Jail stands as a manifesto of individual moral duty against collective indifference. It also showed King's increasing impatience with not just overt racists but with what he called the 'appalling silence of the good people'. Indeed, one can see in King's tone a righteous anger at how group conformity and caution among the mainstream (including the church) allowed segregation to persist.

Notably, in the same letter, when labelled an 'extremist', King initially felt hurt, but then he embraced the term, turning it on its head: 'Was not Jesus an extremist for love... Will we be extremists for hate or for love?' This reclaiming of the extremist label was King's way of saying: Yes, I am outside your norm - and I choose to be extreme for justice rather than remain moderately complicit in injustice. He was proud to be an outsider relative to the unjust consensus. This exemplifies the DRH point that society often ostracises those who don't fit the mould, yet those are the ones who propel moral progress. King aligning himself with historical 'extremists' like Jesus and Lincoln underscored that being out of step with an immoral society is a badge of honour.

Soon after King's release, the Birmingham Campaign reached a dramatic climax. SCLC made the controversial decision to involve school-age children in the demonstrations (the Children's Crusade). On May 2 and 3, 1963, as waves of exuberant youths marched, Bull Connor unleashed police dogs and high-pressure fire hoses on them. The brutal images flashed across television screens worldwide: young Black children pummelled by water and attacked by snarling dogs. The nation and world reacted with horror. The Kennedy Administration, previously cautious, was jolted into action to negotiate a resolution. By May's end, Birmingham's white business leaders agreed to desegregate downtown stores and public facilities and to start an employment program for Black people. It was a limited victory, but a victory nonetheless. Segregation's facade had cracked under the pressure of nonviolent confrontation and the glare of media.

The Birmingham story illustrated King's strategy at its zenith: create a moral crisis so severe that the broader society, including federal authorities, can no longer ignore it. King had written from jail that nonviolent action 'seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension' that a community refusing to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. He recognised this might sound shocking, but clarified that it was 'constructive, nonviolent tension' necessary for growth. This notion aligns with the individual's role in society: sometimes the one who resists and disrupts the comfortable order is doing so to awaken the conscience of the many. King even favourably invoked Socrates as a 'nonviolent gadfly' creating tension to help people rise from 'the bondage of myths and half-truths'. Indeed, King and his fellow protestors acted as gadflies to the slumbering conscience of America. They were, in essence, deindividuation resisters jolting the deindividuated mainstream to examine itself.

However, such actions came at personal cost. The toll on King's mental and physical well-being was real. The FBI's campaign against him escalated in 1963 after Birmingham and especially after the March on Washington in August. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 28, 1963) was the largest civil rights demonstration in U.S. history up to that time, and King was its final speaker. It was here that he delivered the immortal I Have a Dream speech, a moment that catapulted him to an even higher level of international acclaim. In his soaring oratory, King laid out a vision of a nation where 'my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character'. His dream was deeply Individual-centric: it was about people being valued as unique persons, not pigeonholed by group identity. He dreamed of former slave-owners' descendants and former slaves' descendants sitting together at the 'table of brotherhood' - an image of human unity beyond historic enmity, precisely what a society of Individuals rather than Social Persons might look like. He invoked the founding creed that 'all men are created equal', holding America to its own stated principles. That speech, now iconic, is often remembered for its poetic crescendo; but it's crucial to realise it was not just feel-good rhetoric. It was a challenge to America to become what it claimed to be. It was also an implicit rebuke of white supremacist ideology and of any idea that people should be proud of their collective identities such as race instead of judging each person justly. King's dream was the antithesis of us-vs-them thinking - he spoke of 'all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing ... "Free at last!"'. In NSM language, King was painting a picture of a horizontal society of equals (Individual orientation) rather than a vertical hierarchy (Social Person orientation).

The impact of the March on Washington was profound. It put massive pressure on political leaders. Just weeks later, tragedy struck when white supremacists bombed Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church on a Sunday, killing four little girls - a grim reminder of the hatred still entrenched. King delivered the eulogy for three of those girls, yet another scene requiring superhuman composure. In 1964, partly propelled by the momentum of Birmingham and the March, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing segregation in public facilities and discrimination in employment. This was a huge legislative win for the movement. That same year King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and at age 35 became its youngest recipient. In his Nobel acceptance, King reiterated his faith in nonviolence and donated the prize money to civil rights groups, underscoring that his mission was not personal aggrandisement but collective liberation.

Yet, 1964 also marked an important shift: the beginning of open fissures in the movement and intensifying opposition from the government. After the Nobel Prize announcement, FBI Director Hoover - humiliated that 'his' country was celebrating someone he viewed as a subversive - publicly slandered King as 'the most notorious liar in the country' in November 1964. This was unprecedented: the head of the nation's top law enforcement calling a private citizen (and internationally respected figure) a liar. Under Hoover's direction, the FBI also mailed King the notorious 'suicide letter' around this time - a poison-pen anonymous missive accompanied by audio tapes of King's alleged private sexual moments, which threatened him by saying 'King, there is only one thing left for you to do... You know what it is.' It strongly implied King should kill himself or be exposed (the letter even gave a 34-day deadline). The letter dripped with hatred, calling him 'an evil, abnormal beast' and a fraud. Here was the U.S. government, representing the collective power structure, essentially attempting to psychologically destroy an individual who challenged that structure. It is a stark example of how far the 'guardians of the status quo' would go to stop someone who refused to fall in line. King, however, did not crack. He told associates the letter had to be from the FBI (correctly discerning the source) and pressed on with his work. This resilience is extraordinary. The DRH hypothesis notes that resisters often face being 'ostracised and pathologised' - indeed the FBI tried to pathologise King as perverse and menace him with isolation. But King's sense of self was strong; he derived validation from his deep religious faith and the righteousness of the cause, not from the approval of authorities. That inner strength - essentially immunity to deindividuation attempts - enabled him to weather even these vile attacks.

Meanwhile, within the civil rights movement, new ideological currents emerged. Younger activists in groups like SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) grew impatient with the slow pace of change and the brutality that met nonviolence. After the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, where three civil rights workers were murdered, and continued violence in places like Alabama, more militant rhetoric gained traction. In 1965, during the voting rights marches, King worked with SNCC and other groups. But by 1966, SNCC had new leaders like Stokely Carmichael who popularised the slogan 'Black Power'. To King, 'Black Power' as a cry expressed valid frustration and a call for Black political and economic strength. However, he publicly distanced himself from any interpretation of it that meant Black separatism or hatred. King believed in multicultural integration and feared 'Black Power' could harden into just a mirror image of the white racism it opposed. As he wrote, it could be 'an invitation for him [the Negro] to seek identity in separation and isolation from the rest of America' - a path he disagreed with. Here again, King held to universalist, integrative principles even when it put him at odds with more radical Black activists. He was often the target of criticism - some young militants called him too moderate, or even 'Uncle Tom' - a bitter pill for a man who daily risked his life. But King did not retaliate against them; he understood their pain. In fact, the empathy that DRH associates with individual identities was evident - King could relate to their anger but appealed to them that hate would corrupt their souls and violence would undermine their goal. This internal movement tension shows King's delicate balancing act: he was resisting not only white-dominated norms but also resisting the pull of retaliatory group identity within his own ranks. To illustrate, the Neurological Spectrum might place King near the Individual extreme, whereas someone like Carmichael might have been moving from an individual approach to a more collectivist Black nationalist stance, focusing on racial identity solidarity (which, while understandable, clashed with King's insistence on judging by character, not colour). King's consistent position was 'we must not become the thing we seek to destroy.' His opposition to collective hatred - whether by race or by nation - remained firm.

By the mid-1960s, Martin Luther King Jr had reached the height of influence but also isolation. After Selma in 1965 and the passage of the Voting Rights Act, King turned his attention to the northern ghettos and economic inequality. In 1966, he moved his family temporarily into a run-down apartment in Chicago's West Side to draw attention to housing discrimination. The Chicago Freedom Movement he led faced intense resistance. In one march through a white neighbourhood in Marquette Park, Chicago, King was hit by a rock and jeered by a hateful crowd. He commented that 'I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I've seen here today.' Unlike in the South, King didn't achieve dramatic success in Chicago - the agreements he got from the city were mostly unenforced. This campaign left him somewhat frustrated, but undeterred in his broader critique: America had to confront racism not just as Southern segregation but as de facto injustices everywhere, and beyond that, poverty and economic exploitation.

This broadening of focus, and his strident anti-war stance in 1967 cost King support from politicians, the press, and even some civil rights colleagues. The media that lauded him for “I Have a Dream” now chastised him for opposing the Vietnam War. For example, a New York Times editorial said King had made a 'serious tactical error' in intermixing civil rights with peace, and that it might cause white backlash. The Washington Post's April 1967 editorial (quoted earlier) bluntly stated King's anti-war stance 'has done a grave injury to his natural allies... and an even graver injury to himself', predicting many who respected him would never again listen to him. Essentially, they were saying: 'Stay in your lane.' This is reminiscent of what Vincent Harding observed as racial paternalism: voices implying that King should stick to 'Negro issues' and not speak on foreign policy. King's very reply to such warnings was telling: he would often answer, 'I'm sorry, you don't know me. I cannot be silent about things that matter.'. Again, the primacy of individual judgment over others' expectations is evident. As a deindividuation resister, King could not relinquish his autonomy of conscience to any group's notion of what he should do - not even the civil rights establishment or liberal allies. King's longtime colleague and friend Reverend Ralph Abernathy recalled that even some in SCLC's board were nervous about the anti-war position and felt it might hurt the organisation. But King stood firm, willing to endure criticism. According to Dorothy Cotton, a close aide, 'Martin was very much pained by the criticism. He really took notice of what people were saying.' He was human - these things hurt him. 'But,' she added, 'it didn't hold him back. My very clear impression is that the criticism made him delve even deeper into the way of nonviolence.' This insight is powerful: the more King was pressed to conform or tone it down, the more he doubled down on his core principles. It's as if challenges only refined his commitment. This fits the DRH view that some resisters, when persecuted, become even more convinced of the need to maintain integrity (rather than caving to pressure, which is what most would do).

By 1968, King was moving toward a new campaign that he knew would be an uphill battle: the Poor People's Campaign. He planned a massive nonviolent occupation of Washington, D.C., by poor Americans of all races - Blacks, whites from Appalachia, Latinos, Native Americans - to demand an 'economic bill of rights' for the poor. This was the most radical in terms of policy (it challenged class inequality and militarism head-on) and potentially the most controversial protest (an extended encampment in D.C.). The FBI's memos show they were deeply alarmed by this idea. King was aware his enemies would stop at nothing; he confided to friends that threats on his life were pervasive. Indeed, in speeches King began to allude to the possibility of dying and the importance of continuing without him.

In late March 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee, to support Black sanitation workers striking for union recognition and better conditions after two of their colleagues had been accidentally killed on the job. Their slogan, 'I Am a Man', resonated with King's philosophy - these men were asserting their individual dignity against a system that treated them as expendable. On March 28, a scheduled peaceful march in Memphis erupted in chaos when some young attendees started breaking windows. The violence appalled King - it was the first time one of his events had turned disorderly. He left Memphis under a cloud, feeling he had to regroup and prove nonviolence could work. Despite advisers telling him his reputation might suffer, he insisted on returning to Memphis to lead another march. This insistence to 'go back and get it right' showed King's personal sense of responsibility and honour. He could have avoided the risk; instead he put himself right back in the fray, unwilling to let the story end with a failed attempt. That decision sealed his fate.

On the rainy night of April 3, 1968, at Mason Temple in Memphis, King gave what would be his final sermon, nicknamed I've Been to the Mountaintop. In it, he rallied support for the sanitation workers and spoke of the struggle in broad terms. Toward the end, he seemed to have a prophetic moment, reflecting on the bomb threats that had been made against him that day. He said: 'Like anybody, I would like to live a long life - longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain, and I've looked over, and I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But... we as a people will get to the Promised Land.' By all accounts, the crowd was electrified and deeply moved. King ended by saying he was happy, not fearing any man, declaring 'Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.' The next day, April 4, 1968, at 6:01 PM, as King stood on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel speaking with colleagues, a sniper's bullet tore through his neck. King died within an hour at age 39.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr was a shattering event. It provoked an outpouring of grief among Black Americans and all who had followed him. Despair and anger over his murder led to riots in over 100 U.S. cities that April - a tragic eruption of the violence King had so long preached against. It was as if the dam broke. Some observers noted the bitter irony that King died violently after advocating nonviolence, and that after his death America burned - whereas when he lived, he had been able to keep anger from boiling over by offering a nonviolent channel. Indeed, one of King's roles was as a 'pressure valve' to prevent violent rebellion by providing hope. With him gone, hopelessness fuelled chaos.

On a personal level, King's family - Coretta Scott King and their four children (Yolanda, Martin III, Dexter, and Bernice) - had lost a husband and father. Coretta, a formidable figure in her own right, would carry on aspects of his work, founding the King Centre and lobbying for a national holiday in his honour. King's funeral was held on April 9, 1968, in Atlanta, where more than 100,000 mourners lined the streets as a humble mule-drawn wagon carried his casket. In that moment, King, who in life was harassed and denounced as an extremist and traitor by some, was eulogised as a martyred prophet. The striking thing is how American society's perception of King transformed after his death. During his final years, as we've seen, he was highly controversial. But over time, a broad consensus grew that King had been right about segregation (nearly everyone now condemns segregation) and that his advocacy of nonviolence and equality was an exemplar of moral leadership. In 1983, legislation was signed to create Martin Luther King Jr Day as a U.S. federal holiday every third Monday of January, first celebrated in 1986. This was the culmination of a campaign that Coretta Scott King and many others led. Today, King is one of the few individuals (and the only private citizen aside from presidents) honoured with a national holiday in the United States. His memorial stands on the National Mall in Washington, and countless streets and schools bear his name.

Chapter 4: Posthumous Legacy - The Resister's Influence on Society

In death, Martin Luther King Jr has become a symbol of justice, nonviolence, and hope worldwide. But it is important to remember that during his life, he was a dissident voice, a challenger of the status quo, not the universally beloved icon we commemorate today. Society often tames the memory of radicals once they are gone. King's legacy, when examined through DRH and NSM, is precisely that of a person who dragged an unwilling society forward. Initially vilified by many (segregationists hated him; moderates scolded him; the FBI treated him as enemy number one), King is now almost universally praised, with politicians across the spectrum quoting his words. This turnabout underscores a pattern: yesterday's troublemaker can become tomorrow's hero once the dust of conflict settles and their cause is validated by history. As the DRH suggests, 'progress, by definition, happens outside the norm' - and once progress is achieved, what was once outside the norm can become the new norm.

King's legacy operates on multiple levels:

1. Social and Legal Change: King's leadership was instrumental in the passage of key legislation - the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 - which dismantled the legal framework of segregation and enfranchised millions of Black voters in the South. These were tangible victories achieved by collective action inspired by King's ideals. He demonstrated the power of nonviolent protest to bring about concrete change. In the decades since, those laws have been foundational in continuing efforts for racial equality (although the struggle is ongoing). King's work also inspired the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (passed just days after his assassination, partly as a tribute), which aimed to end discrimination in housing. Essentially, King helped spur America to begin aligning its laws with its professed ideals.

2. Shift in Public Consciousness: Perhaps even more profound is the moral imprint King left. He managed to reframe the narrative around race and justice in America. Before, demands for civil rights were often marginalised. King made civil rights a central, inescapable issue of American discourse. He forced people to confront the hypocrisy of a free nation tolerating caste-like conditions for a segment of its population. Through his speeches, he articulated arguments that have become moral common sense: e.g., that people should be judged by character, not skin colour, that injustice for some is a threat to all, that nonviolent protest is not only politically effective but ethically necessary. These ideas are now part of the global vocabulary of human rights. One could say he helped shift a portion of society from the Social Person mindset (clinging to racist traditions) toward a more Individual-oriented recognition of common humanity. His insistence on empathy and love, even for one's adversaries, remains a challenging ideal but has penetrated far - influencing movements from anti-apartheid in South Africa to campaigns for democracy and minority rights worldwide. Figures like Nelson Mandela and the Dalai Lama have openly cited King's influence.

3. Inspiration to Future Resisters: King's life story serves as a template and inspiration for subsequent generations of activists and deindividuation resisters. Whistleblowers, dissidents in oppressive regimes, students standing up to authority - many draw inspiration from King's example of speaking truth to power nonviolently. The DRH notes that two-thirds of all people, as demonstrated in the Milgram Experiment, obey authority to harmful ends, but the minority who resist often do so citing moral convictions - King's legacy bolsters those convictions. When one thinks of the archetype of moral courage, King is often one of the first names that comes to mind, alongside Gandhi or Rosa Parks. This is hugely significant: whereas many historical figures are remembered for wielding power or violence, King is remembered for moral and spiritual power. He demonstrated that an individual armed with integrity and nonviolence can mobilise masses and bend the arc of history. His life thus validates the DRH's claim that progress depends on the few who won't conform to evil.

4. Integration into National Identity - and Tensions: Over time, Martin Luther King Jr has been absorbed into the narrative of what America prides itself on. Politicians of all stripes invoke his dream to claim support for their policies. Yet this canonisation can sometimes sanitise King's more radical critiques. The King who opposed the Vietnam War and planned to disrupt D.C. over poverty is less frequently mentioned in mainstream commemorations. In fact, in recent years, scholars and activists have sought to reclaim the full complexity of King, reminding the public that he died campaigning for workers' rights and denouncing economic inequality and war. The national memory tends to focus heavily on 1963 'I Have a Dream' King, sometimes at the expense of 1967 'Beyond Vietnam' King. This selective memory is itself a function of collective identity dynamics - societies prefer comfortable heroes. King, however, was never truly comfortable for society. Even today, invoking King's true positions can be provocative. For instance, King's assertion that 'my own government is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world' remains controversial yet relevant as a moral critique of militarism. His call for a 'radical revolution of values' against materialism, militarism, and racism challenges the United States as much now as it did then.

Thus, part of King's legacy is an ongoing challenge. He left a blueprint, but unfinished work. Fifty-plus years after his death, racism and inequality persist. In some ways, the collective identities that King fought - like white supremacy or violent nationalism - mutate and linger. Movements such as Black Lives Matter explicitly draw on King's tradition of protest, yet they also highlight how far there is to go. King's writings and speeches remain a wellspring for those pushing for criminal justice reform, economic justice, and nonviolent approaches to conflict.

From the perspective of the Neurological Spectrum Model, one could say that King helped move the needle of society a bit further toward the “Individual” side. Laws that enforced group hierarchy (Jim Crow) were abolished. Interracial cooperation became more normalised; the us-vs-them narratives around race were at least partially weakened by King's vision of interracial brotherhood. He popularised the idea that loyalty to ethical principles must trump loyalty to groups. For example, his influence can be seen in how many Americans, during the Vietnam War and subsequent conflicts, felt compelled to protest rather than fall in line - because King had modelled that dissent is sometimes the highest form of patriotism. He taught that conscientious objection is valid - a very Individual concept that one's own conscience can veto the commands of the state or the clamour of the crowd.

Looking at King through the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis one last time: King embodied practically every trait of that hypothesis. He maintained his own identity (as a Christian minister of a certain philosophy) rather than simply mimic the identities around him. Even within the Black community, he carved a distinctive identity - not every Black leader agreed with him on nonviolence or interracial approach, but King didn't bend to peer pressure either. He certainly didn't 'just follow orders' - whether it was ignoring unjust injunctions in Birmingham or saying no to President Johnson on the war, King showed a rare independence from authority. He didn't follow the crowd - he often went against prevailing sentiments (e.g., 70% of Americans disapproved of his anti-war stance in 1967). He took responsibility for his actions - writing the Birmingham letter to explain himself, going to jail willingly, and ultimately giving his life. Meanwhile, those on the extreme Social Person end - say the segregationist sheriffs or the obedient silent majority - often claimed they were 'just doing their job' or 'it's just the law' (as in Milgram's experiment, they passed off accountability). King was the polar opposite: he felt personally accountable to do the right thing, and if that meant breaking the law, he did so openly and accepted the penalty. In one moving anecdote, after an unjust court injunction in Birmingham, some advisers said, why don't we just quietly ignore it or find a legal loophole. King refused: 'I'm going to jail. If we disobey, we do it openly and humbly. We must practice what we preach.' That ethical consistency is hallmark of an integrated Individual identity.

Even King's personal struggles - times of depression, alleged marital infidelity, etc. - can be seen as the immense strain the resister bears. The DRH suggests that resisting social conditioning comes with stress and potential trauma. King shouldered not just a social burden but a psychological one. The FBI's relentless harassment exploited his vulnerabilities to try to break him. That he kept going is a testament to his resilience and the support system he had (family, close friends, faith). It reminds us that resisters are human. King was not a lone superhero - he had moments of doubt, he needed encouragement (as in that midnight kitchen prayer). But crucially, he found the strength to persevere in resistance where most would cave.

To conclude this biography through our chosen lens, Martin Luther King Jr can rightly be called a 'Great Soul' (the meaning of Mahatma, the title given to Gandhi). In terms of the neurological spectrum between individual and collective identity, King resided firmly on the individual side - guided by his own moral compass, empathy for all, and vision of a better future. He did not let the ambient noise of society's prejudices, fears, and hatreds deafen the inner truth he perceived. Instead, he acted as society's conscience, striving to elevate the collective to a more enlightened state. King's life validates the hypothesis that one person's integrity can indeed resonate with the innate sense of justice in others, leading enough people to resist an unjust status quo and eventually force change. In so doing, he also validated the American creed - exposing how America had failed it, but also lighting a path toward its fulfilment.

King's assassination was an unspeakable loss, but as he predicted, 'we as a people will get to the Promised Land.' That promised land - a world where each person's dignity is respected and no one is judged by involuntary group traits - remains on the horizon. Yet it is closer because Martin Luther King Jr lived. His life story, refracted through the DRH and NSM, teaches that progress is neither automatic nor easy: it requires individuals with uncommon courage to stand up, at great cost, against deeply entrenched collective norms. It requires what King called 'creative extremists' to push the boundary of the acceptable toward the truly just. King was such an extremist for love and justice. He pulled America forward, and in the process, he provided a roadmap for all who would resist dehumanisation in any form.

In one of his sermons, King said, 'Cowardice asks: is it safe? Expediency asks: is it politic? Vanity asks: is it popular? But conscience asks: is it right?' Martin Luther King Jr consistently asked, 'Is it right? - and once he saw the right, he pursued it, unsafe, unbought, and unpopular if need be. His conscience - the Individual within - was the ultimate authority he obeyed. By answering that inner call, King changed the world. His biography, viewed through the lens of individual vs. collective identity, confirms the immense power and necessity of those rare individuals who, in every generation, refuse to lose themselves in the crowd. Martin Luther King Jr shone as a bright example of a deindividuation resister who by remaining true to himself helped redeem the soul of his nation, and whose legacy continues to inspire the ongoing journey toward freedom and equality for all.

Sources:

• King Institute, Stanford University: Major King Events Chronology (1929-1968); King Encyclopedia (entries on King National Holiday and FBI and King).

• Martin Luther King Jr, “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (16 April 1963), via Dickinson College Archives.

• Martin Luther King Jr, “I Have a Dream” speech (28 August 1963), reported by History.com.

• Martin Luther King Jr, “Beyond Vietnam – A Time to Break Silence” speech (4 April 1967), via Digital History (University of Houston).

• Martin Luther King Jr, “I've Been to the Mountaintop” speech (3 April 1968), excerpt via Wikipedia.

• The Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (Frank L. Ludwig, Autism as a Social Construct).

• The Neurological Spectrum Model (Frank L. Ludwig, Between Individual and Collective Identity).

• APM Reports, King's Last March (American Public Media, 2018) – analysis of King's final year.

• Vox, “Read the letter the FBI sent MLK to try to convince him to kill himself” (2014).

• NWTRCC, “MLK on War and Civil Disobedience” (2014).

• King, Autobiography of MLK Jr (ed. Clayborne Carson) – King's recollections of childhood events.

• House Divided Project, Dickinson College – Introductory bio of King.