Charles Robert Darwin (1809–1882) stands as a towering figure in science – a gentle, introverted naturalist whose independent mind reshaped humanity's understanding of life. In an age when religious and social orthodoxies dominated intellectual life, Darwin developed his theory of evolution by natural selection, a truth that defied the prevailing collective beliefs of Victorian society. This biography examines Darwin's life through the combined lens of the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (DRH) and the Neurological Spectrum Model (NSM) - frameworks that illuminate how individuals who resist social conditioning and groupthink drive human progress. According to DRH, most people undergo social conditioning (a deindividuation process) to fit into social groups, whereas rare individuals retain their authentic identity and perspective despite pressure to conform. NSM likewise posits a spectrum between the Individual - one who acts on personal judgment, immune to outside influences - and the Social Person - one who unquestioningly absorbs group norms. Charles Darwin exemplified the far end of the Individual orientation: he pursued truth based on observation and reason, even when it conflicted with collective dogma, and he maintained personal integrity over the comfort of compliance. As we will see, Darwin's character and choices - from his curious childhood and bold voyage on the Beagle, to his hesitant unveiling of a theory that 'knocked God out of the causal chain' in biology - reveal a man who resisted the social pressure to think and believe as others did. In doing so, this humble yet brilliant introvert changed the course of science and society.

Charles Darwin's life will be explored in depth, covering his upbringing in a freethinking family, his formative experiences and education, the five-year voyage that transformed his mind, and the painstaking development of his theory of natural selection. We will trace how Darwin's introverted disposition and 'retiring yet influential' personality shaped his work. Emphasis will be given to how Darwin demonstrated DRH/NSM-aligned traits at each stage: questioning authority and tradition, gathering evidence with obsessive focus, and ultimately formulating a revolutionary idea that he knew would defy the centuries of traditional theistic thinking about nature. We will see how he navigated the intense social, religious, and scientific pressures of his time without succumbing to ideological conformity - how he delayed publication out of caution and care for others, yet never abandoned his conviction in the face of potential ostracism. Through psychological analysis, we'll interpret Darwin's struggles - the tension between his scientific discoveries and his personal or religious beliefs - as the internal experience of a mind firmly rooted in the Individual end of the neurological spectrum. His reluctance to engage in public disputes, his preference for writing over speaking, and his quiet courage in championing an unsettling truth all reflect the pattern of a deindividuation resister. Finally, we will consider the broader legacy of Darwin's ideas in the context of collective vs. individual identity structures: how the theory of evolution challenged entrenched group identities (especially religious doctrines of human uniqueness), and how society's eventual acceptance of Darwin's insights illustrates the dynamic between pioneering individuals and the collective worldview.

Structured as a narrative with clear chapters, this comprehensive biography interweaves the story of Darwin's life with an analysis of his mindset and values. It includes comparisons with his contemporaries to situate Darwin on the neurological spectrum relative to his peers, highlighting those who embraced or resisted new ideas. Through this combined historical and psychological lens, Darwin emerges not just as a scientist, but as an exemplar of how an independent, truth-seeking individual can transform collective understanding.

Chapter 1: Early Life and Family Background (1809-1825)

Family Origins and Influences: Charles Darwin was born on February 12, 1809, into a wealthy and intellectually curious family in Shrewsbury, England. He was the fifth of six children of Dr. Robert Waring Darwin - a successful physician - and Susannah Darwin (née Wedgwood). The Darwin-Wedgwood clan was prominent and well-connected; his paternal grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, had been a physician and poet with radical scientific ideas (even foreshadowing evolution), and his maternal grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood, was a renowned pottery industrialist and abolitionist. Young Charles grew up amidst the comforts of the family estate called The Mount, doted on by his older sisters especially after his mother's untimely death when he was just eight. The extended family's liberal and scientific leanings created a protected and stimulating environment. From early on, Charles was exposed to ideas of observing nature and valuing evidence - seeds of an individualistic outlook. His father encouraged Charles' interest in natural history (botany was Dr Darwin's own hobby) even as he insisted on a traditional education in the classics. This balance of support and expectation set the stage for the quiet tug-of-war between Charles' individual passions and the social pressures of his class and time.

A Young Naturalist with an Independent Streak: Darwin later recalled that from his earliest years he had a passion for collecting and for the outdoors, and that formal schooling did little to nourish his mind. He was first educated at day schools and then, at age 9, sent to the strict Shrewsbury School as a boarding student. There, he was required to focus on Latin, Greek, and rote learning - the standard fare for a gentleman's education - but Charles found it dreary. In his autobiography he bluntly wrote: 'Nothing could have been worse for the development of my mind… the school as a means of education to me was simply a blank'. Instead of excelling in class, he did the minimum work needed and devoted his energies to pursuits that truly interested him: roaming the countryside, observing plants and insects, collecting beetles, bird's eggs, rocks and minerals. 'Darwin was born a naturalist,' one biographical account notes - he spent long hours happily 'rummaging through his father's gardens and land looking for interesting critters,' completely absorbed in studying the natural world. This childhood behaviour - prioritising personal curiosity over imposed academics - hints at an innate resistance to social conditioning. The DRH framework suggests all children begin life with individual identities and authentic interests, but most are gradually pressed into conforming to group norms. Young Charles, however, held onto his authentic love of nature despite schooling that valued classical studies over scientific inquiry. Rather than internalise the era's expectation that a boy of his status should be a diligent classical scholar, he effectively followed his own path, an early sign of the individual orientation that would define him.

Darwin's independent streak was also evident in the little 'experiments' of his youth. Along with his older brother Erasmus, he became fascinated by chemistry and they set up a homemade laboratory in the garden shed. The two boys eagerly followed popular chemistry manuals to perform experiments - producing various reactions and probably some awful smells in the process. Their enthusiastic tinkering earned Charles the nickname 'Gas' among schoolmates. This mild mockery did not deter him; he continued pursuing what intrigued him regardless of peer opinions. According to the NSM, an Individual-oriented person 'says what they mean and what they know to be true', not merely what is expected by others. In actions, young Darwin similarly did what he found meaningful, not just what authority figures demanded. His willingness to ignore ridicule and persist in his hobby foreshadowed the thicker skin he would need as an adult challenging society's deepest beliefs.

Hobbies, Field Sports, and Character: In his adolescence, Charles' passions oscillated between naturalism and the quintessential country gentleman's sport of shooting. For a few years as a teenager he became obsessed with hunting - frequently joining his cousins or friends on shooting outings to hunt birds in the woods. He was a good shot and initially revelled in this socially approved pastime. Yet even here, hints of Darwin's distinctive compassion and reflective nature emerged. Over time, he grew uncomfortable with killing animals for sport. One story relates that he came upon a bird he had shot the day before that was still alive and suffering; another tells of him receiving an insect specimen in the mail that arrived alive but injured. In both cases, Darwin was moved to end the creatures' suffering gently rather than continue hunting heedlessly. These incidents apparently dampened his zeal for shooting. By the time he voyaged on the Beagle in his twenties, he often hired others to do necessary shooting of specimens, as his own enthusiasm for pulling the trigger waned. This growing empathy aligns with Darwin's later staunch moral stance against cruelty (for example, his strong opposition to slavery). It also resonates with the NSM description of the Individual identity: 'The Individual loves diversity and individual expression… The Individual believes that it's morally wrong to hurt anybody else,' whereas the conforming Social Person is more prone to justify violence or cruelty under group-sanctioned practices. As a youth, Darwin was still finding his moral footing, but the trajectory of his interests - moving away from mindless group activities (like hunting parties) and toward compassionate study of life - suggests a psyche orienting toward the Individual end of the spectrum, valuing life and truth over social entertainments.

Charles' father, Robert Darwin, grew concerned that his son might become an 'idle sporting man' - one of the leisured gentlemen who spent all day on horses and hunts with no serious career. Seeing young Charles more passionate about dogs, guns and beetles than about his studies, Dr. Darwin once scolded him sharply: 'You care for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching, and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family.' This harsh rebuke was born of a parent's fear that Charles was squandering his potential and shirking the conventional path to success. Ironically, the very activities that worried his father (the obsessive collecting, the fixations on natural curiosities) were signs of Charles' scientific temperament and focus - traits that would later fuel his groundbreaking work. The generational tension here is telling: the elder Darwin represented the pressure to conform to respectable norms (earn a degree, join a profession, uphold the family reputation), whereas Charles' instincts pulled him toward exploration and inquiry outside those norms. Under DRH, this is a classic scenario: a youth's innate individual identity coming up against the forces of social conditioning that demand compliance. Charles did attempt to oblige his family at first, but in the end he would find an unconventional route to both make his family proud and stay true to himself.

Religion and Early Scepticism: Though not overt in his childhood recollections, Darwin's attitude toward religion in youth also hints at an independent mind. The Darwin family were nominally Anglican, but Charles' mother's family (the Wedgwoods) were Unitarian - a more liberal Christian denomination - and religious observance in the household was not strict. As a boy and young man, Charles dutifully attended church and even memorised Bible verses when required, yet he harboured private doubts. Later at Cambridge, training for the clergy, he confessed to friends that he struggled with certain doctrines and was not entirely convinced by Anglican theology. This was the beginning of a gradual drift from the collective religious identity that most of his society shared. In the NSM framework, a Social Person strongly identifies with group beliefs (such as a church's teachings) and suppresses personal doubts in order to belong. Darwin, by contrast, quietly allowed his personal reasoning to question what he was taught. He did not make a show of rebellion - indeed, outwardly he still appeared the polite clergyman-in-training for a time - but internally, the seeds of freethinking were germinating. He later wrote that by age 40 he had ceased to believe in the Bible as divine revelation, on logical and moral grounds. In fact, he recalled that by 1842 (in his early 30s) he had largely abandoned whatever remained of his Christian beliefs, rejecting the authority of scripture and finding doctrines like eternal damnation morally repugnant. Such a break with faith did not come all at once in his youth, but the independence of thought that allowed it can be traced to the curious, slightly sceptical boy who valued evidence over authority - a boy who would grow into a man bold enough to redefine humanity's origins.

In summary, Charles Darwin's childhood and teenage years reveal an inquisitive mind often at odds with the educational and social expectations placed upon him. He was curious, observant, and single-minded about his interests - qualities that mark him as an individual in NSM terms, one who sees the world directly rather than through society's lens. He also showed signs of the DRH prototype: an innate identity resisting full assimilation into collective norms, even if it meant being seen as odd or underperforming by his peers and parents. The very traits that made him seem an unimpressive student - wandering the fields, collecting beetles, avoiding the beaten path - were the foundation of his greatness as a naturalist. As the next chapters will show, those traits would be tested and strengthened by the transformative experiences of Darwin's young adulthood.

Chapter 2: Cambridge Education and the Voyage of the Beagle (1825-1836)

Deserting Medicine for Nature: In 1825, at age 16, Charles Darwin was sent to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, following in the footsteps of his father and brother to study medicine. This was a pivotal juncture where the tension between parental/social expectations and Darwin's own inclinations became acute. At Edinburgh, Darwin quickly discovered that he had no passion or stomach for medical training. He found anatomy lectures dull to the point of disgust - writing home that he disliked the anatomy professor's class so much he could not speak of it 'with decency' - and he was horrified by the brutality of surgical operations (conducted without anaesthesia in those days). In one incident, young Darwin fled the operating theatre mid-procedure, unable to watch a child being operated on while awake. This visceral aversion to surgery derailed any hope that he would become a doctor like his father. Instead of attending medical lectures, Charles spent his Edinburgh days in pursuits that actually engaged him: he eagerly took Professor Robert Jameson's natural history course, learning to identify rock strata and fossils in the field; he thrilled at the theatrical chemistry lectures of Thomas Hope; and he passed hours on seaside walks collecting marine creatures and taking taxidermy lessons from John Edmonstone, a freed South American slave who taught him how to stuff birds. By effectively skipping the expected path and crafting his own ad-hoc education in natural science, Darwin demonstrated the classic DRH trait of resisting undesired social conditioning. The vast majority would have dutifully slogged through an unfulfilling degree for the sake of family and status, but Darwin's inner compass prioritised authentic interest over conformity.

During his second year at Edinburgh, Darwin's disengagement from the formal program only deepened. He joined no classes at all in medicine and even failed to register for the library (a telling sign he wasn't invested in the official curriculum). However, he immersed himself in the student scientific community. He became an active member of the Plinian Society, a club of radical young naturalists that met to discuss new ideas - often challenging traditional supernatural explanations of the natural world. In this setting, Darwin flourished. He attended talks on zoology and botany, debated classmates on topics like species classification and animal behaviour, and even gave his first scientific presentation at the society in 1827, reporting his original observations on marine organisms (how tiny larvae of a bryozoan could swim using cilia, and the discovery of eggs of a species of leech on oyster shells). Notably, he did this at only 18 years old - an early sign of scientific creativity and confidence. Darwin also befriended Dr Robert Grant, a zoology professor and outspoken proponent of evolutionary ideas (specifically, he admired Lamarck's theories). Grant took young Darwin under his wing, and on long walks along the Firth of Forth they discussed the 'unity of plan' in the animal kingdom and the possibility of common descent of species. Grant shared with Darwin his belief that all life might have originated from simple forms, exposing him to evolutionary thinking years before Darwin would formulate his own theory. This mentorship was transformative: it planted in Darwin the notion that questioning the fixity of species was not only possible but scientifically important. In NSM terms, Darwin was gravitating toward peers and mentors who embodied the Individual side - people who challenged orthodoxy and followed evidence. This incubator of free thought at Edinburgh strengthened Darwin's resolve to pursue knowledge on his own terms, even as his failure in medical studies loomed.

Ultimately, Darwin quit Edinburgh without a degree in 1827, an outcome his father viewed as a severe disappointment. Robert Darwin, alarmed that Charles was now an idle dropout, devised a new plan: Charles should become an Anglican clergyman. The thinking was pragmatic - if Charles wasn't cut out for medicine, a respectable post as a country parson would provide a steady living, social status, and ample leisure for a gentlemanly pursuit of science as a hobby. Charles, acknowledging he had no better plan and genuinely not averse to the idea at the time, agreed to this path. To become a clergyman, he needed a degree from Cambridge University, so in 1828 he enrolled at Christ's College, Cambridge.

Cambridge: Finding Purpose in Science (1828–1831): At Cambridge, Darwin's official aim was to complete a Bachelor's degree and then take holy orders in the Church of England. Unofficially, however, he treated his university years as an opportunity to further indulge his scientific interests. He was a competent but unenthusiastic student in the required subjects (mathematics, Classics, theology), never rising beyond the middle of the pack academically. He later admitted he was more interested in beetle collecting than in Greek grammar or divinity studies - a fact borne out by his exploits. Darwin became famous on campus for his zeal in hunting down rare beetles in the fens and woods around Cambridge. Along with his cousin William Darwin Fox and other like-minded undergraduates, he scoured the countryside, often coming back muddy and triumphant with specimens. In one comedic anecdote, Darwin recalled finding himself holding two beetles (one in each hand) when he spotted a third of a rare kind; desperate not to lose it, he popped one beetle in his mouth for temporary storage, only to have it discharge a foul acid that burned his tongue - causing him to spit it out and lose both that one and the third beetle in the commotion. Such was the passion and single-minded focus of the young naturalist. This intense focus on a narrow interest is notable: it is precisely the kind of restricted interest often seen in autism spectrum personalities, which can lead to exceptional expertise. Indeed, modern commentators have speculated that Darwin showed several traits of autism - he was 'a very quiet person who avoided social interactions', preferred communication in writing over speaking, and was very focused on his work. Whether or not Darwin would today be neurologically classified on the spectrum, his Cambridge behaviour fits the DRH/NSM profile of an individual driven by deep intrinsic interest, relatively unconcerned with the broader social college life that didn't advance that interest.

Crucially, Cambridge introduced Darwin to key figures who shaped his future. He became close with Professor John Stevens Henslow, a respected botanist, clergyman, and widely beloved teacher. Henslow recognised Darwin's enthusiasm (if not brilliance) in natural history and welcomed him into his circle of student protégés. Darwin spent countless hours walking with Henslow, discussing science, collecting plants, and learning to catalogue observations carefully. It was said that Darwin became 'the man who walks with Henslow', so constant was his presence at the professor's side. Another influence was Reverend Adam Sedgwick, a geology professor who took Darwin on a field expedition in Wales during the summer of 1831 to map rock strata and collect fossils. From Sedgwick, Darwin learned rigorous methods of geological observation, further honing the empirical mindset that would serve him in developing evolutionary theory. Notably, despite Darwin's earlier doubts about some religious doctrine, at Cambridge he did not revolt against the idea of becoming a clergyman - in fact, the peaceful life of a country parson-naturalist rather appealed to him at that moment. This shows Darwin was not a contrarian for the sake of it; he was willing to follow a conventional career so long as it left room for his true passion. In NSM terms, he was navigating a balance: outwardly fulfilling a collective role (an Anglican priest) while inwardly maintaining his individual identity as a naturalist. He hadn't yet been forced into an outright conflict between personal truth and social expectation - that would soon come with his scientific discoveries.

The Voyage of the Beagle - Opportunity Beckons: Having earned his BA degree in early 1831, Darwin was back home in Shropshire in the summer, preparing for a future in the clergy. Then came the turning point of his life. In August 1831, Darwin received an unexpected letter from his Cambridge mentor Henslow. It contained an invitation that made Darwin's heart race: the Royal Navy survey ship HMS Beagle was to embark on a voyage to chart the coasts of South America, and Captain Robert FitzRoy was seeking a naturalist companion to join him. The position wasn't an official naval appointment (Darwin would sail as a gentleman volunteer, not as paid crew), but it offered a young scientist the chance to explore far-flung regions, collect specimens, and observe nature on an epic scale. FitzRoy wanted not just a collector but a social equal to dine with - someone who could keep him company and help avoid the loneliness that had driven the Beagle's previous captain to suicide. Darwin, bursting with 'enlarged curiosity; and inspired by travelogues like Alexander von Humboldt's, was immediately keen to go. However, his father staunchly opposed the idea at first. Dr Darwin saw a long voyage as a foolhardy distraction from the serious business of settling down; he famously declared it nothing but a waste of time for Charles, slamming the door on the proposal - unless some credible person could convince him otherwise.

In a display of determination (and perhaps a bit of strategy), 22-year-old Charles turned to his maternal Uncle Jos (Josiah Wedgwood II) for support. Uncle Jos was more sympathetic to Charles' scientific dreams. He wrote a persuasive argument to Dr Darwin extolling the voyage as a glorious opportunity for a young man of Charles' talents and 'enlarged curiosity'. Together, Charles and Uncle Jos met with Dr Darwin and managed to change his mind - the father relented, giving his blessing and even offering to cover Charles' expected expenses for the trip. This family negotiation is telling: rather than rebel openly, Darwin found an ally within his family to help bring the patriarch around. It shows Darwin's tact and aversion to direct confrontation (a consistent trait), but also his quiet resolve to get what he felt he needed for his own path. Winning his father's approval, Darwin was ecstatic - only to be crestfallen again by a misunderstanding. It turned out the offer to sail on the Beagle was not assured to Darwin; FitzRoy had also been considering a friend for the post, and initially Darwin was told that friend would get the spot. For a brief time, Darwin thought his dream had slipped away and wrote that he had 'entirely given it up'. But soon FitzRoy's friend declined, and Darwin was summoned to London for an interview. The meeting almost went awry: FitzRoy, a believer in physiognomy, nearly rejected Darwin because he thought the shape of Charles' nose indicated a lack of determination. Fortunately, FitzRoy overcame this absurd impression and officially offered Darwin the berth on the Beagle. Delighted, Darwin accepted. The voyage was on.

On December 27, 1831, the HMS Beagle finally set sail from England, with Charles Darwin aboard as the ship's naturalist and gentleman companion to Captain FitzRoy. Thus began a nearly five-year odyssey around the world (far longer than the originally planned two-year survey). Darwin later reflected that 'the voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life, and has determined my whole career.' Indeed, it was during this expedition (1831-1836) that Darwin gathered the observations and experiences that would lead him to question the fixity of species and eventually conceive the mechanism of natural selection. The Beagle voyage was not only a scientific expedition but also a profound personal journey, shaping Darwin's identity further toward the independent end of the spectrum. Over the course of the trip, he was often isolated from traditional social structures (aside from the ship's crew and occasional contacts), giving him freedom to think for himself. He encountered a stunning diversity of life and cultures, challenging the parochial worldview he grew up with. And he maintained a singular focus on collecting data - a kind of obsessive dedication that again speaks to his ability to hyper-focus, arguably an autism-spectrum advantage ('hyperfocus, persistence, seeing detail that others missed, endless energy for a narrow task, and independence of mind' were qualities that one psychiatrist later attributed to Darwin's mode of work).

Life Aboard and Afar: Darwin's role on the Beagle was multifaceted. Formally, he was the ship's naturalist, expected to collect specimens of plants, animals, rocks, and fossils at various stops, and to keep careful notes. Since he was not a naval officer, he paid his own way (with family funds) but he had the run of the ship's quarterdeck and shared the officers' mess. FitzRoy, coming from an aristocratic background himself, treated Darwin as a social equal and companion. In fact, one reason FitzRoy wanted someone like Darwin was to talk to - he dreaded the mental strain of isolation during a long voyage, especially given his family history of depression (a fear tragically realised many years later when FitzRoy died by suicide in 1865). Darwin's presence was intended to provide camaraderie and intellectual stimulation for the captain, and by most accounts it did - though not without friction. The two men generally got along well, sharing refined conversations over dinner and collaborating on charting and survey tasks (Darwin often assisted with on-deck measurements). However, their personalities and worldviews sometimes clashed. FitzRoy was a devout Christian, a Tory conservative, and staunch believer in the literal truth of the Bible, while Darwin was more liberal and inquisitive. Famously, they argued only once fiercely - over the issue of slavery. While in South America, Darwin witnessed the horrors of slavery and called it an atrocity; FitzRoy, though a man of integrity in many respects, defended the practice or at least downplayed its evils. Darwin was incensed at FitzRoy's indifference to the suffering of enslaved people, and their exchange grew heated, ending with FitzRoy's temper flaring. It speaks volumes that this was the sole major quarrel: Darwin normally avoided confrontation, but on a moral issue so fundamental, he stood his ground even against his benefactor the captain. His abolitionist stance was likely influenced by his family (the Wedgwoods were abolitionists) and by his own empathy when seeing slavery firsthand. In terms of NSM, Darwin in this incident acted as an individual who regards others as equals and believes that it's morally wrong to hurt anybody else, whereas FitzRoy was behaving more as a social person defending his society's established hierarchy and norms. The fact that Darwin did not capitulate to FitzRoy's viewpoint, even at risk of straining their relationship, shows a moral independence - he would not conform on matters of conscience. (FitzRoy later apologised for losing his temper in that argument and they resumed cordial relations, but the episode left a strong impression on Darwin.)

During the voyage, Darwin was often seasick and found long stretches at sea tedious, but whenever the Beagle anchored and he could go ashore, he came alive with purpose. He trekked through Brazilian rainforests, rode with gauchos in the Argentine pampas, climbed the Andes in Chile, observed volcanoes and earthquakes, and of course visited the Galápagos Islands - all the while collecting thousands of specimens and filling notebooks with observations. It's important to note that Darwin did not have his evolutionary theory figured out during the voyage itself. He was collecting data and noting puzzling patterns, some of which would later be crucial clues. For example, in the Galápagos (September-October 1835), he observed that each island had its own unique species of mockingbird and noticed subtle differences in tortoise shells from island to island. He heard from locals that tortoises differed by island, but at the time he didn't fully grasp the significance - he even mistakenly thought the tortoises might have been introduced by humans. He collected many Galápagos finches as well, but initially failed to label them by island (an oversight he later regretted), because he didn't realise they were all distinct species of finch; to his eye they were just a mixed flock of similar small birds. The eureka that these species were related yet distinct came only after returning to England and consulting expert ornithologists like John Gould. In short, Darwin had no sudden epiphany in the field about evolution. As one historian notes, 'there was no "Eureka!" moment' in the Galápagos - the realisations dawned on him slowly with hard work later.

However, what the voyage did was profoundly expand Darwin's mental horizons. He saw with his own eyes that the distribution of species made little sense under the assumption of independent creation of each form. Why would neighbouring islands have similar but slightly differing creatures? Why would fossils of giant extinct mammals in Patagonia resemble smaller living species in the same region? Why did the Andes contain fossil seashells high up in their rocks (suggesting dramatic change over time)? These observations collectively planted the idea that species are not fixed, that they change and adapt - but Darwin had yet to conceive how. During the journey, Darwin kept extensive journals (later published as Journal of Researches, also known as The Voyage of the Beagle). His meticulous note-taking and collection efforts reflect his methodical, focused mind. Crew members noted how tirelessly Darwin worked whenever on land - rising early, shooting birds or catching insects, tagging and preserving specimens, scribbling notes late into the night. This level of dedication impressed everyone. It's the kind of intense focus that the NSM's individual can yield, and which DRH suggests is often misunderstood or pathologised by society when seen in unconventional contexts. In Darwin's case, during the voyage he was in a supportive context for his focus - the Beagle officers and crew recognised the value of his scientific work. Captain FitzRoy, despite their ideological differences, was generally supportive of Darwin's endeavours; he gave Darwin freedom to explore inland and facilitated his research. The British Admiralty too indirectly valued Darwin's contributions – the specimens and reports he sent back sparked interest among naturalists at home. Darwin was thus in a unique bubble where his individualistic pursuit of knowledge was not only tolerated but somewhat encouraged (at least by scientific peers), even if the larger society hadn't yet confronted his ideas.

By the time the Beagle circumnavigated the globe and returned to England in October 1836, Charles Darwin was a changed man of 27. He came back with a naturalist's treasure trove and a mind awhirl with questions. He no longer simply catalogued nature; he wanted to explain it. Crucially, he was already entertaining the radical notion (privately) that species might not be immutable. Within months of his return, Darwin's diary shows him contemplating the 'transmutation of species'. In July 1837 he opened a secret notebook (Notebook B) in which he began sketching ideas about how species evolve, even drawing a crude tree of life diagram with the note 'I think' above it. In one telling reflection from his notes, Darwin wrote: 'It is like confessing a murder…' to admit that one believes species are not God-ordained and immutable. This oft-quoted line (from a letter Darwin penned to his friend Joseph Hooker in 1844) reveals the psychological weight he felt - he knew that openly contradicting the creationist view of life would be seen as heretical, almost a crime. That he compared it to murder highlights how deeply the collective religious belief in divine creation was ingrained in society - and how grave a transgression it seemed to break from it. Yet, Darwin was increasingly convinced that the evidence demanded this transgression. Here we clearly see the DRH dynamic: Darwin, as a deindividuation resister, was willing to hold a viewpoint that could make him ostracised and pathologised. He only admitted his heresy to a trusted few at first (fearing social rejection), but he did not abandon the idea. His individual identity as a seeker of truth had solidified. The voyage gave him the data and the confidence to trust his own judgment over the prevailing wisdom of the group. He had literally travelled the world and seen reality in all its diversity - he could no longer be content with the parochial, static truths he had been taught.

Thus, by the end of the Beagle voyage, Charles Darwin had completed the transition from an aspiring young naturalist to a scientist with a dangerous idea. He had also by necessity further developed the personal traits that allowed him to carry that idea: patience, self-reliance, careful reasoning, and a willingness to privately dissent from authority. As the next chapter will explore, the period after his voyage - as he formulated and honed his theory - would test Darwin's nerve and integrity in new ways. He would have to decide how and when to present his individual discovery to a potentially hostile collective. The shy young man who dreaded making waves would find himself the bearer of a revolutionary concept. How he managed this burden, and how he continued to embody the DRH/NSM traits through the turmoil of revealing his theory, is the focus of the next part of his life's story.

Chapter 3: Developing a Revolutionary Theory in Private (1836-1858)

Settling into Scientific Life: Upon returning to England in 1836, Charles Darwin was received as something of a rising star in scientific circles. His collections of exotic specimens and fossils were eagerly examined by experts, and his travel diary from the Beagle was in demand even before publication. In London, Darwin moved among established naturalists like geologist Charles Lyell and anatomist Richard Owen, who respected his observations. However, Darwin did not revel in public attention; true to his introverted nature, he preferred to work quietly behind the scenes. He busied himself organising his notes and specimens, writing papers on his findings (such as the formation of coral reefs), and supervising the publication of his travel journal. By 1839, he married his cousin Emma Wedgwood and soon retreated to a peaceful country life - first to a house in London's outskirts and then, in 1842, to Down House in Kent, a secluded rural home. This move to the countryside was partly due to Darwin's health (which had begun to suffer with frequent nausea, fatigue and heart symptoms) and partly a deliberate choice to avoid distractions. Darwin found that in the bustle of London, social obligations and endless meetings could consume his time and energy. In Kent, he could control his schedule and work at his own pace. 'Continuous ill health saved me from the distractions of society and amusements,' Darwin later remarked, half in jest. Indeed, his chronic ailments often provided a convenient excuse to decline invitations and remain in his beloved daily routine of study, experimentation, and family time. In his own words, from the early 1840s onward he travelled very little, avoided social engagements as 'a waste of time', and maximised solitary work hours. This self-imposed seclusion is characteristic of Darwin's personality - he was much more comfortable pouring over observations in his study or walking alone in his 'sandwalk' path at Down House than attending soirees or scientific congresses. The NSM Individual archetype puts their work first and cares little for social frivolities, which is exactly what Darwin did. His personal needs and ego were modest; he cared mainly about getting the science right.

Formulating Natural Selection: During these two decades of relative quiet (1837-1858), Darwin gradually worked out the theory that would make him immortal. It was a slow, painstaking process - not a lightning bolt of insight but a cumulative reasoning from countless facts. By 1837 he was convinced species changed over time. The big question was how. In 1838, while reading economist Thomas Malthus' essay on population, Darwin hit upon the mechanism: the 'struggle for existence' in nature could lead to preservation of favourable variations - natural selection. As Darwin later recounted, upon this idea dawning on him, 'at last I had a theory by which to work'. He privately fleshed out the theory over the next few years, writing a detailed 35-page sketch in 1842 and expanding it to a 230-page essay in 1844. Yet, he published none of this at the time. Why? Darwin hesitated - famously, for about twenty years. Several factors contributed to this long delay before publishing On the Origin of Species in 1859. First, Darwin was keenly aware that his theory would be controversial and feared the 'storm of controversy' it would unleash. He wrote in 1844 that announcing his belief in species evolution felt like confessing to murder, as noted, indicating how scandalous the idea seemed even to him. He was by nature conflict-averse and did not relish the prospect of public attacks or of hurting those who held contrary religious beliefs. Second, Darwin deeply cared about the feelings of his wife, Emma, who was a sincere Christian. She once gently warned him in a letter that she feared for his soul if he lost his faith. Darwin, loving and respecting Emma, was pained by the thought of distressing her with a theory that undercut her religious worldview. This personal conflict weighed on him. Third, Darwin's scientific temperament urged caution and completeness. He didn't want to publish a groundbreaking theory without overwhelming evidence and without anticipating every possible objection. So he kept gathering data - breeding pigeons to test variation, studying barnacles for years to understand small differences between species, consulting with botanists and biogeographers about distribution of organisms, etc. As Darwin himself said, he wanted to have 'carefully thought through and addressed every possible objection' before going public. And indeed, On the Origin of Species would be a densely argued book with an avalanche of supporting examples. Fourth, he was genuinely sidetracked by other projects and health issues. Notably, he took an eight-year 'detour' to become the world's expert on barnacles, dissecting and classifying hundreds of specimens (1846-1854). While this might seem a diversion, it actually strengthened his credibility and honed his skills - by the end of it, Darwin was a respected taxonomist, which helped others take his later arguments seriously. It also exemplified his perseverance and capacity for deep focus, hallmarks of his character. His ability to spend eight years on the minutiae of barnacle anatomy testifies to an almost obsessive diligence (the kind that might be linked to autism, giving him 'endless energy for a lifetime dedication to a narrow task', as one expert put it).

Thus, Darwin's delay was a mixture of strategic patience, personal anxiety, and methodical preparation. Some peers later criticised him for not publishing sooner, but in truth Darwin was navigating the tricky intersection of individual conviction vs. collective creed. The DRH would interpret his behaviour as a resister's careful attempt to minimise the personal cost of defying the collective. Rather than martyr himself by rushing out a radical idea and facing immediate outrage, Darwin subconsciously (and consciously) gave himself time, building a fortress of evidence around his idea and letting Victorian society gradually warm to the possibility through others' discussions. During the 1840s and 50s, there was a growing undercurrent of evolutionary speculation in scientific circles (e.g. Robert Chambers' anonymous 1844 bestseller Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation floated a less scientific evolutionary idea, sparking debate). By the mid-1850s, the notion of species transmutation was slightly less shocking than it had been in 1837, though it was still widely rejected in polite society. Importantly, Darwin did share his theory in confidence with a few close colleagues well before 1859 - Joseph Hooker, Charles Lyell, and Thomas Huxley among them - and they became trusted sounding boards. Hooker, initially sceptical, came to be convinced of Darwin's views over years of correspondence. Lyell, the great geologist, was cautious but supported Darwin behind the scenes. In one remarkable acknowledgment, Darwin noted that in all his years of investigation he 'had not encountered anyone who seemed to doubt the permanence of species. Even Lyell and Hooker… never seemed to agree' until he gradually won them over. This shows how isolated Darwin was intellectually at first - he truly was one of a very few individuals questioning the deep status quo of biology. It also highlights his persistence: 'by sheer persistence and belief that he was right, a characteristic happily possessed by few, Darwin changed the minds of the leading scientists of his day'. That line, from historian Tom Frame, encapsulates the DRH idea in practice. The majority of learned men initially resisted Darwin's concept (they were on the more collective, conformist side of the spectrum regarding species fixity), but Darwin's unwavering commitment - that rare trait - gradually shifted the consensus. His quiet evangelical mission, via letters and evidence, was to convince the scientific community one person at a time, before facing the broader public.

An Introvert's Low-Profile Tactics: During the development of his theory, Darwin exhibited what one might call 'quiet courage'. He did not trumpet his ideas from rooftops, but neither did he abandon them. Instead, he worked steadily, almost covertly, to strengthen the argument. He was keenly aware of his social context and managed his reputation carefully. Financially, Darwin was secure - his father's estate and prudent investments gave him ample income, meaning he didn't depend on an academic or clerical position. This independence was critical: 'Darwin had the means to pursue his own research interests and do what he thought was important, without having to justify his decisions to an institution', as Tom Frame points out. Unlike a professor or clergyman, Darwin had no superiors to answer to, no need to 'just follow orders' or stick to orthodox views to keep his job. His wealth afforded him the freedom to be unconventional. Of course, many in his social class had wealth, but few chose to make waves intellectually. Darwin did, but in his own understated way. He often tested the waters by soliciting opinions. For instance, he asked animal breeders about variations and hybridisations, gaining practical knowledge to bolster his theory (later much of this went into Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication). He was effectively crowd-sourcing supporting evidence, all the while not fully divulging his endgame. This method exemplifies Darwin's strategic, risk-averse approach: gather a network and data quietly such that when the theory finally drops, it carries an aura of thoroughness and inevitability.>BR>

Throughout these years, Darwin also struggled with ill health, which cannot be ignored in its influence. He suffered frequent bouts of stomach pain, vomiting, severe fatigue, heart palpitations, skin rashes, and other symptoms. The cause is still debated (proposed diagnoses range from a tropical parasitic disease like Chagas, to chronic anxiety disorder, or some psychosomatic illness). What's notable is that his symptoms often flared up during stressful periods - for example, when writing his first sketch of the species theory in 1842, he became ill, and the pattern repeated whenever he pushed himself. This suggests that the psychological stress of working on something so controversial likely took a physical toll. In a DRH sense, one might say Darwin internalised the conflict between his individual insight and the weight of collective disapproval in the form of stress-related illness. Yet, even his illness served his purposes in a way: it enforced his seclusion and provided a polite excuse to avoid gatherings where awkward questions might arise about his views. Darwin at times felt guilty for dodging direct confrontation, but as he confided to Huxley later, he simply did not have the constitution for public brawls. Instead, he let others take up that mantle, while he focused on finishing his magnum opus.

By 1856, urged by Lyell that others might publish similar ideas first, Darwin began writing a full-length treatise on natural selection. He envisioned it as a large, multi-volume work. But fate intervened in a dramatic way before he could complete it. In June 1858, Darwin received a letter from a naturalist colleague, Alfred Russel Wallace, who was in the Malay Archipelago. To Darwin's shock, Wallace enclosed a manuscript detailing a theory of evolution by natural selection virtually identical to Darwin's own. Wallace politely asked Darwin to show it to Lyell if Darwin thought it worthy. This moment was a crucible for Darwin. All his years of guarded secrecy suddenly threatened to amount to nothing - someone else might get credit for the theory. To Darwin's everlasting credit, he did not react selfishly or with attempts to undermine Wallace. Instead, deeply distressed (and at the very same time dealing with the tragic death of his young son from scarlet fever), Darwin turned to Lyell and Hooker for counsel. The solution Lyell and Hooker devised was to arrange a joint presentation of Wallace's paper along with some of Darwin's unpublished extracts at the Linnean Society in July 1858, thus establishing both men's contribution. Darwin, grieving his child and reluctant to appear in public, did not attend the meeting. The matter was handled tactfully, and while the event itself made little immediate splash, it lit a fire under Darwin: he realised he must finally publish his work or lose the chance to be recognised as the primary discoverer of natural selection. Summoning what energy his fragile health allowed, Darwin set to condense his big manuscript into a single accessible volume. In an extraordinary sprint of productivity, he wrote most of On the Origin of Species in about 13 months and saw it through publication in November 1859.

Integrity and Personal Risk: It's worth noting Darwin's attitude during the Wallace incident. Even though he certainly wanted credit for his years of labour, he was remarkably gracious and modest. He wrote to Lyell that it was 'miserable in me' to care about priority while his baby had just died, implying that personal glory was trivial in the face of life and death. He truly wasn't driven by fame or ego; he was motivated by the desire to see the truth unveiled. In fact, Darwin later remarked that while he valued the approval of scientific peers, becoming known to the general public didn't matter to him, and he regarded caring about one's rank or status in society as a foible. This detachment from egotism is part of what made Darwin such a sincere seeker of knowledge. It also aligns with the NSM Individual mentality: pride for the Individual lies in personal achievements or integrity, not in social standing or titles. Darwin exemplified this - he took pride in his carefull research and in being right, not in being lauded. He did become a Fellow of the Royal Society and received some honours, but he avoided any whiff of self-promotion. When On the Origin of Species was about to be published, he did not plan a public lecture or flashy announcement. Instead, he quietly coordinated with colleagues to ensure the book reached influential scientists and reviewers. He entrusted allies like Hooker and Huxley to defend the work in public arenas, as needed.

As Darwin finalised On the Origin of Species, one can imagine the emotional and mental resolve it took. He was fully aware that he was lifting a veil on something that could upend humanity's view of itself. He wrote to Lyell that his book was 'not more unorthodox than the subject makes inevitable', noting that he had deliberately steered clear of the most inflammatory topics (he didn't discuss human evolution in it, nor Genesis explicitly). He was trying to introduce the idea as palatably as possible: focussing on plants and animals, emphasising that he believed in laws ordained by the Creator (a subtle placation to religious readers by using the word 'Creator' in the text). Yet, the implications were unmistakable and he knew it. Darwin anticipated that many would draw the conclusion 'little or no role for creation by God' from his arguments. He tried to preempt some criticism by addressing supposed evidence of design (for instance, acknowledging the complexity of the eye, which he admitted seemed absurd at first glance to attribute to natural selection, then explaining step by step how it could evolve). In doing so, he demonstrated intellectual honesty - he didn't hide the hard problems but faced them - and empathy for the reader who found the theory hard to swallow. This reflective approach likely stemmed from Darwin's own gradual grappling with the idea over decades. He understood the collective mindset he was challenging, because he had been raised with those beliefs himself. This allowed him to frame his arguments gently but firmly.

By late 1859, Darwin had done all he could to prepare. The book went on sale on November 24, 1859, titled On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The first print run of 1,250 copies sold out immediately. Now Darwin's private theorising was a public matter, and the reaction began - setting the stage for the next chapter of his life, where his ideas confronted the world and he navigated the aftermath.

Chapter 4: Publication, Public Reaction, and Controversy (1859-1865)

The Bombshell Drops: The publication of Origin of Species in 1859 was a watershed moment in science and Victorian society. Though technical in parts, the book was written in clear, accessible prose and aimed at educated lay readers as much as specialists. Darwin's central claim - that species were not independently created but evolved from common ancestors through a natural mechanism - struck at the heart of conventional beliefs. As expected, a storm of reaction ensued. In the scientific community, many younger naturalists and some progressive thinkers quickly embraced Darwin's theory, impressed by the massive accumulation of evidence and the elegant logic tying it together. Older, more established scientists and clergy-naturalists reacted with scepticism or hostility. The press and public followed suit, with newspapers and magazines debating the idea widely. Importantly, Darwin's prediction about readers inferring the exclusion of God was accurate: although Origin tactfully avoided direct mention of humans, everyone realised the implications. If natural selection explained design in nature, then the special creation of humans (and indeed all life) as described in Genesis was called into question. The Victorian public, for whom the literal truth of the Bible was still a cornerstone, was confronted with a theory that 'raised as many new questions concerning religion and ethics as did Copernicus' or Newton's ideas', perhaps even more. One contemporary observed that Darwin's work forced people to reconsider 'the validity and cogency of religious claims' in a fundamental way.

While Origin did not instantly convert everyone to evolution, it succeeded in putting the topic on the forefront of intellectual discourse. Darwin himself, however, did not engage in public debates or defences of his book in person. Here his introversion and strategic acumen came to the fore. As soon as Origin was published, Darwin retreated to Down House, citing ill health (which indeed flared up from the anxiety and exertion of publication). He left the public battling to his friends and allies. For instance, Darwin corresponded with the botanist Asa Gray in America, equipping him to write a favourable review that reconciled evolution with design (Gray, a devout Christian, argued one could see natural selection as God's method). In England, two of Darwin's closest scientific friends, Thomas Henry Huxley (a brilliant comparative anatomist) and Joseph Hooker (a botanist), took on the mantle of chief defenders of Darwin's theory. Huxley, in particular, relished the fight. Known as 'Darwin's bulldog', Huxley spoke and wrote vigorously in support of evolution and countered critics in public forums. Darwin orchestrated quietly from behind the scenes: he wrote letters to influential scientists and reviewers, supplied data or clarifications as needed, and expressed his arguments in subsequent editions of Origin. But he did not appear on lecture tours or at heated debates. As noted earlier, he engineered reviews and publicity from eminent people by correspondence, but 'instead of going on a lecture tour… he delegated that to two friends, Huxley and Hooker.' This conscious delegation shows Darwin's understanding of his own strengths and limits. He was a master of written communication and one-on-one persuasion, but he knew he was not a strong or willing public orator. In today's terms, we might say Darwin played to his strengths and let extroverted, combative allies handle the spotlight.

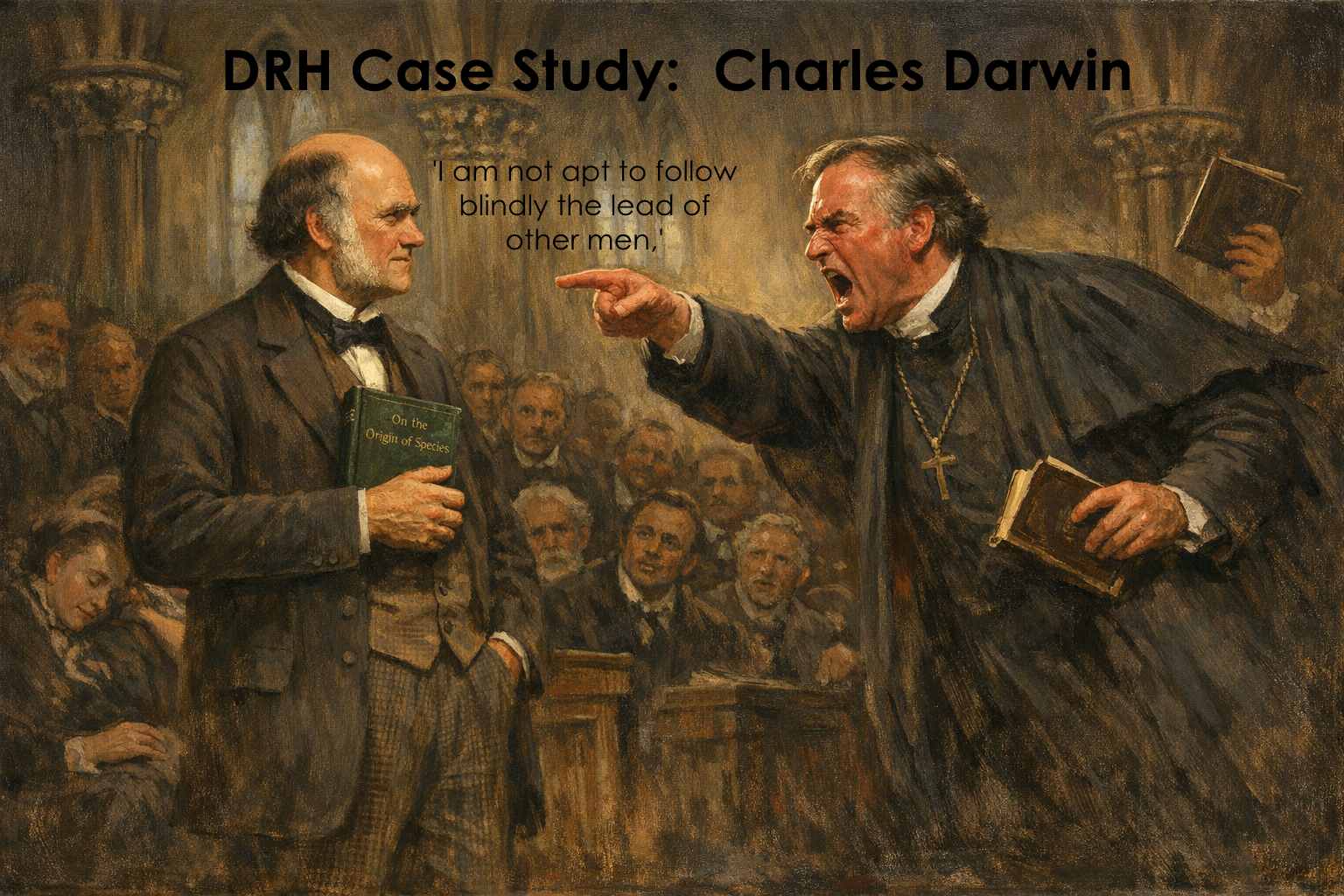

This approach was remarkably effective. For example, the most famous public confrontation over Darwin's ideas took place at the Oxford University Museum in June 1860, just months after Origin came out. Samuel Wilberforce, the Bishop of Oxford (and a polished orator), publicly critiqued and ridiculed Darwin's theory during a meeting of the British Association. Wilberforce, embodying the voice of religious orthodoxy, appealed to the audience' sense of propriety, asserting it was absurd and degrading to think humans may be descended from an ape'. He had allies among the eminent scientific establishment too - Richard Owen, for one, sided with Wilberforce in rejecting Darwinism at that time. On the other side, Thomas Huxley rose to respond. In what became a legendary exchange, Huxley defended Darwin's theory as a truth that must be accepted if evidence supports it, regardless of how humiliating it might be to human pride. Huxley famously retorted (to a jibe the Bishop made about Huxley's ape ancestry) that he would not be ashamed to have an ape for a grandfather, but he would be ashamed to be connected with a man who used great gifts to obscure the truth. Eyewitnesses reported that the audience was electrified. This debate was a proxy war: Church vs. Science, collective tradition vs. individual reason. Wilberforce, wielding the authority of the Church and entrenched social values, declared that such an idea as Darwin's ought not to be true. Huxley, representing the empirical investigator, declared that he and those like him were willing to accept truth, 'even [the] last humiliating truth of a pedigree not registered in the Herald's Office' (i.e. even the shame of an ape ancestry). This dramatic line encapsulates the difference in identity orientation. The Bishop and his supporters could not stomach an idea that undercut the collective identity of humans as God's special creation. Their identity was bound up in a hierarchical view with man just a little lower than angels. Huxley and the Darwinians, by contrast, valued facts over feelings, individual inquiry over tradition. As Huxley said, they were willing to accept any actual truth even if it wounded their pride.

Darwin wasn't present at that debate - he was home in Kent, reading accounts of it later with interest. Admiral FitzRoy, Darwin's old captain, was in attendance and, overwhelmed by conscience, he stood up during the meeting, brandished a Bible and implored the crowd to 'believe God rather than man'. He dramatically declared he 'regretted the publication of Mr. Darwin's book.' This poignant moment showed how even some who knew and liked Darwin personally (FitzRoy had been a friend) felt compelled by their collective loyalties to reject his ideas utterly. FitzRoy's identity as a Christian and gentleman could not reconcile with being an accomplice to this evolutionary heresy, and he publicly repudiated it, tears in his eyes, asking the audience's pardon for his role in enabling Darwin's work. Such scenes illustrate how Darwin's theory cut into the emotional core of people's collective worldviews. Under DRH analysis, one might say Darwin's idea threatened to strip away a layer of deindividuation - the comfort people took in thinking of their group (in this case, the human species, or one's religious community) as exalted and separate. The thought of human-primate kinship provoked visceral disgust in some, precisely because it humbled the collective ego ('Man in his arrogance thinks himself a great work… more humble to consider him created from animals', Darwin would later write). Accepting Darwinism required a kind of personal courage to detach one's identity from the old narrative and adjust it to a new reality - a move from the Social end toward the Individual end, in NSM terms. Many did make this move over time, especially younger intellectuals and those already inclined to doubt literal Biblical accounts. But many others dug in, and some still do generations later, attesting to the power of collective identities to resist change.

Darwin's Measured Responses: How did Darwin himself handle the swirling controversy? Characteristically, with modesty, restraint, and reason. He did not respond to critics with anger or personal attacks. In fact, when some creationist detractors tried to impugn his character or suggest he had bias due to a materialistic worldview, Darwin largely ignored such barbs, focussing on substantive scientific issues. One of his few direct public responses was to add new material to later editions of Origin addressing points raised by critics. For example, after the 1860 Oxford debate and other critiques, Darwin revised Origin in its 3rd and 4th editions to clarify misconceptions. He even added the famous closing line in later editions mentioning life 'having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one', which slightly appeased some readers by implying God started the process. (Privately, Darwin didn't necessarily hold that belief strongly at this point, but he was willing to use a deistic veneer to reduce backlash.) This could be seen as a pragmatic compromise with the collective sentiment - not falsifying his theory, but framing it in a way less threatening to believers. It shows Darwin's tact. He always sought to avoid unnecessary conflict. As Tom Frame noted, 'He disliked conflict and confrontation but was ready to defend and debate his ideas when he thought they were misunderstood or misrepresented. He was unwilling to join a dispute if it generated just more heat and not a great deal of light.' This sums up Darwin's approach perfectly. If critics raised valid scientific queries (e.g. about gaps in the fossil record, or the mechanism of inheritance which Darwin admittedly didn't yet understand), he engaged those - often through correspondence or additions to his work. But if someone merely hurled insults or loud religious condemnations, Darwin generally stayed above the fray, letting others respond if needed. He wrote to friends with frustration at times, for instance calling some opponents 'old fogies' in private, but he maintained public decorum and never demeaned his adversaries in print.

Darwin was also protective of his family throughout this turbulent period. He knew his wife Emma feared public notoriety and scandal. He tried to reassure her and shield her from the nastier criticism. At one point, when absurd rumours spread that Darwin had recanted on his deathbed (a false anecdote that emerged years later), one of Darwin's children and Emma herself firmly denied it - indicating how important it was to them that Darwin's integrity be preserved. Even in 1859-1860, as controversy raged, Darwin cared more about how his ideas might affect those close to him than about his own reputation. He wrote that he was especially concerned for his family's well-being amid the public furore. This again underscores his humility and kindness. He wasn't a crusader out to aggressively convert the masses; he was a sensitive soul who wanted truth to prevail but hoped it could do so without causing harm to people he loved or to society. In fact, Darwin believed - and time would prove him right - that in the long run his theory would ennoble our understanding of life rather than degrade it. But he anticipated correctly that the adjustment period would be rough.

One striking measure of how much Victorian society came to respect Darwin the man, even when disputing his theory, is that despite all the debates, Darwin himself was not personally vilified to the extent one might expect. Some critics, like Bishop Wilberforce, attempted to cast doubt on Darwin's motives or imply he was impious. There were rumours circulated by some clergy that Darwin's ideas were influenced by personal bias or perhaps by a desire to 'justify immorality' - typical ad hominem attacks from those trying to discredit a dangerous idea by smearing its originator. But those efforts largely failed, in part because Darwin's character was unimpeachable. Even those who disliked his conclusions admitted he was a sincere, modest gentleman and a careful scholar. As one account notes, 'There is nothing in Darwin's character, no moral failing, to which anyone could point that would detract from his ideas or divert observers from their significance. He wasn't devious like [some others]. He wasn't seeking institutional recognition and didn't crave public honours.'. In other words, attacking Darwin's person got opponents nowhere – he had disarmed a lot of that by being so evidently honest and unpretentious. Many who opposed his theory did so on intellectual or theological grounds, not by demonising him (with a few exceptions). Indeed, as early as 1864, Darwin was awarded the prestigious Copley Medal of the Royal Society, indicating his peers recognised his scientific contributions even amid lingering scepticism about natural selection. This grudging respect speaks to Darwin's tactic of keeping the moral high ground. He always framed his work as a scientific pursuit of truth, not an attack on religion. He even wrote in Origin that he saw 'grandeur in this view of life', suggesting a quasi-spiritual awe at evolution's workings. By not positioning himself as an anti-religious firebrand, Darwin avoided triggering the full wrath of Victorian religious establishments in personal terms - much in contrast to, say, T H Huxley or later figures like T H Huxley's grandson Julian, who were more combative publicly.

Meanwhile, acceptance of evolution was steadily growing in scientific circles. By the mid-1860s, the idea that species evolved was gaining traction, though not everyone accepted natural selection as the sole or main mechanism. (Some proposed alternatives like directed evolution or continued to invoke some divine guidance in the process.) But Darwin and his supporters kept accumulating evidence - from biogeography, embryology, anatomy, and palaeontology - that made the old creationist model increasingly untenable scientifically. The collective scientific paradigm was shifting, and Darwin was at the centre of this shift, wielding influence not through charisma or authority but through the weight of evidence and reasoned argument. It is here that we see the power of an individual's persistence eventually changing the collective understanding. The NSM spectrum had many initially on the collective end (defaulting to the established creationist view), but Darwin's clear, patient demonstration of facts caused many to think for themselves on this issue and come to agree with him. As DRH posits, those few who resist groupthink can lead the way, and eventually the group adapts and spreads the new idea - which is exactly what happened with evolution.

By 1865, Darwin had weathered the worst of the storm. His name was famous (or infamous in some quarters), and Origin of Species had gone through multiple editions and translations. While still a private gentleman at Down House, he was now one of the most influential thinkers alive. Remarkably, he remained as unassuming as ever. Visitors to Down House found an old-fashioned, courteous man, loving to his children, eager to discuss barnacles or pigeons, and seemingly oblivious to any grandiosity. He cultivated a sand walk path on his property where he'd take daily walks to think (the family called it his 'thinking path'). In public controversies after 1860, Darwin increasingly stepped back as the theory took on a life beyond its author. Others debated the implications (for example, the heated debates in the late 1860s about whether natural selection could account for human mental faculties or morality). Darwin did contribute later to the discussion of human evolution with The Descent of Man in 1871, finally applying his theory explicitly to humanity. But by then, evolution as a general idea was broadly accepted in science, and the argument had moved to details about the role of natural selection versus other factors.

By the mid-1860s, the controversy had become more normalised - no longer an explosion, but an ongoing debate gradually tilting in Darwin's favour within scientific domains. Publicly, however, evolution remained contentious, especially in more traditional or religious segments of society. Darwin's name had entered into common discourse, sometimes misconstrued (the caricature of 'Darwin says we come from monkeys' became a satirical trope, though Darwin had never phrased it so crudely). The idea also began inspiring broader reflections: philosophers, theologians, and even poets reacted to the new vision of life's history. Darwin, always focused on concrete research, didn't engage much in these broader cultural discussions. He did note with sadness when extreme misapplications of his theory arose - for instance, he was not a supporter of social Darwinism (the notion that human societal progress comes from competition and 'survival of the fittest' in a moral sense). That idea was mainly promoted by others (Herbert Spencer et al.), and Darwin's own writings on human society in Descent of Man emphasised cooperation and sympathy as important evolved traits in civilised societies. Darwin personally was compassionate and abhorred things like war and oppression, which he would have seen as distortions of 'survival of the fittest' if anyone tried to justify them that way. Unfortunately, others in the late 19th century and beyond did co-opt evolutionary language to back various collective ideologies (from imperialist racism to eugenics). That was a legacy of Darwin's work he never intended - a cautionary tale that even ideas born from an independent search for truth can be spun to reinforce harmful collective identities. (For example, some extremists twisted 'survival of the fittest' to rationalise a collective identity of a 'superior race' dominating others, a perversion Darwin would have deplored, especially given his own anti-slavery stance and view that all humans were one family).

Through these turbulent years, Darwin's psychological fortitude was tested but he remained remarkably steady. Friends and family in letters describe him as sometimes anxious or overworked, but never vindictive or despairing. He found solace in continuing to do science - studying barnacles, domestic animals, climbing plants, insect-eating plants, and later earthworms. Whenever a particular controversy grew too hot, Darwin would retreat into the cool refuge of empirical research on a different topic. This not only gave him respite but produced a string of additional scientific contributions that enhanced his reputation further (and incidentally provided yet more evidence of evolutionary principles). It also exemplified how Darwin's mind worked: intense focus on one problem at a time, almost to the exclusion of external noise. That ability to shut out distractions and deeply engage with a subject is characteristic of what many would call a neurodivergent or spectrum trait - and it was key to his productivity.

By the late 1860s, Charles Darwin had survived the initial ordeal of introducing his theory. He was world-famous, often misinterpreted, often lionised, and sometimes demonised, but he himself remained largely the same gentle, thoughtful person. The next chapter will look at Darwin's later years - his further scientific work, his personal life (including tragedies and joys), and how he continued to embody the principles of integrity, independent thought, and humaneness. We will also examine how Darwin's own perspective on religion and society evolved, and how he reconciled (or didn't) the implications of his theory with his earlier beliefs. Finally, we will consider the long-term legacy of Darwin - not just the scientific legacy, but what his life story means in the context of DRH and NSM: how one individual's refusal to surrender his judgment to collective pressures expanded the horizons of collective knowledge, and how the ongoing reception of Darwin's ideas reflects the dynamic tension between individual reason and collective belief in human culture.

Chapter 5: Later Years, Personal Reflections, and Ongoing Research (1865-1882)

Continued Scientific Work: After the tumult of the early 1860s, Charles Darwin settled into a quieter, if still very productive, routine in his later years. Ever the meticulous researcher, he did not consider his work finished with Origin of Species. He had several other projects in mind and poured his energies into them, one by one. In 1862, he published On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, a detailed study of orchid flowers demonstrating how their intricate shapes evolved to ensure pollination by specific insects. This work provided elegant examples of adaptation via natural selection, answering critics who had asked, 'Where is the evidence of intermediate forms or useful transitions?' Darwin showed how even something as complex and seemingly purpose-built as an orchid's structure could arise from gradual modifications. Next, he tackled the question of how variation is generated and inherited with his 1868 book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. There he compiled extensive data from breeders and offered his hypothesis of pangenesis to explain heredity (which, though incorrect, was an honest attempt prior to genetics). In 1871 came The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, where Darwin finally addressed human evolution head-on and introduced his theory of sexual selection to explain traits like the peacock's tail or a bird's song that don't obviously aid survival but affect mating success.

Publishing Descent of Man was a bold step, even a decade after Origin. In it, Darwin made explicit what had been implicit: humans, like every other species, evolved from non-human ancestors. He wrote, 'Man in his arrogance thinks himself a great work, worthy the interposition of a deity. More humble, and I think truer, to consider him created from animals.' This statement was a clear challenge to the collective identity of Victorian humanity. Darwin was fully conscious of the gravity - he knew this claim would almost certainly elicit a strong response. But he felt the evidence compelled him. By 1871, enough fossils of early humans were being found, and comparative anatomy showed undeniable similarities between humans and apes (the very brain structures that Richard Owen once claimed set humans apart were proven by Huxley to be present in apes). Darwin marshalled evidence of commonalities: our skeletal structure, our embryonic development, vestigial organs, and even behaviours that linked us to other animals. He argued that acknowledging our animal origins should not be seen as degrading; rather, it is enlightening. However, he did address the moral and social implications carefully. Darwin contended that human moral sense likely evolved from social instincts (like sympathy, which he observed even in animals to a degree) combined with intellect and habit. In other words, he tried to show that recognising a biological basis for morality and mind does not destroy morality - it just roots it in our nature as social animals.

The publication of Descent of Man indeed stirred fresh controversy, but by then Darwin's ideas had a strong backing and much of the heat had dissipated. Many readers accepted the idea of human evolution, though often with caveats (some suggested God guided it, etc.). Those who rejected it tended to be the same groups that had rejected Origin, and they made their protests known. But one interesting social shift had occurred: by the 1870s, a new generation had grown up with Darwin's name in the air. For them, evolution was less shocking than it had been to their parents. This demonstrates how collective attitudes can shift within a couple of decades, especially under the influence of persuasive evidence and advocates. The majority of scientists by 1880 accepted evolution in some form. Natural selection's primacy was still debated (only in the 20th century would it be vindicated as central), but Darwin's personal scientific reputation was secure. He continued to produce remarkable studies: The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) compared how humans and other animals express feelings, reinforcing the continuity between us and our fellow creatures. In late 1870s, he investigated plant movements and behaviour (in a sense bringing plants into the fold of organisms that show behaviour and adaptation). His final book, The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms (1881), delved into how earthworms slowly but profoundly affect soil - a humble topic yet one that underscored Darwin's overarching theme of gradual, cumulative change making a big difference over time. Fittingly, it was like his life's motto: even the smallest incremental actions (whether worms tilling soil or tiny variations accumulating in a lineage) can, given time, produce monumental effects.

Darwin approached these studies with the same intensity and focus he always had. In fact, as he aged, he became even more absorbed in work. He admitted late in life that he had grown so consumed by scientific pursuit that he lost his earlier tastes for music and poetry, writing, 'I have become a kind of machine for observing facts and grinding out conclusions.' He lamented this 'curious and lamentable loss of higher aesthetic tastes'. This self-reflection suggests that Darwin recognised a certain narrowing of his life - a trade-off he'd made, perhaps unintentionally, by devoting himself so completely to research. It is another hint at what we might today call a touch of the autistic mono-focus: he gained extraordinary satisfaction from scientific problem-solving, to the point where other pleasures fell away. He even mused that if he were forced to stop working, he suspected he would die shortly thereafter - which is exactly what happened, as he literally worked until a week before his death. In one sense, this hyper-focused dedication was the engine of his contributions; in another, it might have reduced his ability to enjoy the moment or indulge in leisurely social or artistic pursuits. Emma Darwin and his children sometimes worried he overworked and isolated himself, but they also understood it was his nature and passion.