Ludwig van Beethoven: A Life of Individuality

Introduction: Beethoven and the 'Individual' Archetype

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) is often celebrated not only as a musical genius but also as a fiercely independent spirit who defied the social conventions of his time. In psychological terms, Beethoven embodies the Individual extreme of the 'Neurological Spectrum Model' (NSM) - a framework positing a spectrum between the Individual and the Social Person in human identity. Those at the Individual end act on personal judgment and remain 'immune to any outside influences', whereas those at the collective end absorb group expectations with 'no sense of individuality'. Beethoven's life reads as a case study in Individualism: he consistently resisted social conditioning and hierarchical authority, aligning with what Frank L Ludwig's Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (DRH) calls a 'resister' of deindividuation. According to the DRH, 'human progress is driven by people who resist social conditioning … and retain their individual identities at the cost of being ostracised and pathologised'. Throughout his biography - from his rough childhood in Bonn to his triumphant yet isolated final years in Vienna - Beethoven's behaviour, beliefs, and creative choices illustrate this resistance to the collective norm. He refused to 'just follow orders' or etiquette simply for conformity's sake, and instead forged his own path in music and life. In this comprehensive biography, we trace Beethoven's life chronologically while interpreting his psychology and sociology through the NSM and DRH lens. Key themes include his rejection of authority and convention, his moral and creative independence, and how his neurological disposition as an 'Individual' may have fuelled his innovations and his struggles.

Early Life in Bonn: Upbringing of a Young Nonconformist (1770–1792)

Beethoven was born on or around December 16, 1770, in Bonn, in the Electorate of Cologne (modern-day Germany), into a family of court musicians. From a very young age, he was subjected to intense musical training by his father, Johann van Beethoven, who hoped to mould Ludwig into a child prodigy like Mozart. Johann's methods were notoriously harsh - 'a rare day that he wasn't locked in the cellar or flogged,' according to accounts of Beethoven's childhood. The boy was forced to practise for hours on end, even woken at night to play, a regimen that instilled musical discipline but also, as some scholars suggest, 'helped foster some of the anger and aggression' later evident in Beethoven's art.

Despite this strict conditioning, young Ludwig exhibited an individual streak early on. He often rebelled against rote repetition. Instead of dutifully playing pieces 'over and over' as instructed, the child preferred to improvise and create his own music - much to his father's ire. According to one famous anecdote, when Beethoven was a boy practicing violin, Johann heard him deviating from the sheet music and furiously scolded him: 'What silly trash are you scratching together now? You know I can't bear that - scratch by note, otherwise your scratching won't amount to much.' This vignette illustrates Beethoven's early resistance to authority and convention: he chafed at simply fulfilling his father's imposed programme (a form of social conditioning in microcosm) and instead followed his own creative impulses, even at the cost of punishment. The Neurological Spectrum Model would describe this young Beethoven as already leaning toward the Individual extreme - asserting personal expression over compliance. Indeed, Beethoven's father's attempt to force a collective identity (the role of 'wunderkind performer' in service of family prestige) was largely unsuccessful; Ludwig retained his authentic musical identity, foreshadowing the 'immunity to outside influences' that he would display throughout life.

Beethoven's formal education was limited - he quit traditional school by age 11 to focus on music. By his early teens, he was already working as a court musician in Bonn, effectively an employee of the Elector's chapel. Under the mentorship of Christian Gottlob Neefe, a progressive court organist, Beethoven learned composition and was introduced to Enlightenment literature and philosophy. Neefe encouraged Beethoven's individual talents: at just 12, Beethoven composed his first works and even had some pieces published. This nurturing of Beethoven's unique voice helped him further develop the Individual identity that NSM describes - his self-concept as a 'unique human' equal to others, not merely a subordinate child or apprentice. Notably, Neefe wrote that Beethoven would 'surely become a second Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart' if given the chance, indicating Beethoven's extraordinary gifts. Yet unlike Mozart (whose father Leopold carefully managed his career), Beethoven was self-driven and often stubborn. Even as a teen, he lacked 'social graces' and could appear 'unkempt, grubby', and awkward - signs that he paid little heed to polishing his image for others. In NSM terms, he did not identify collectively with the polite bourgeois or court society; instead, he interacted on his own terms, comfortable in a somewhat outsider status that valued musical skill over social polish.

At age 16, Beethoven experienced the first major tragedy that reinforced his independent role: his beloved mother died, and his father's alcoholism worsened. Beethoven effectively became head of the family for his two younger brothers, an experience that likely deepened his self-reliance and perhaps distrust of authority (his father being a failed authority figure). In 1792, with support from patrons in Bonn, Beethoven seized the opportunity to move to Vienna - Europe's musical capital - to study composition with the great Franz Joseph Haydn. The move marked the end of Beethoven's Bonn years and the beginning of a new chapter where his individualistic tendencies would become even more pronounced.

Vienna Beginnings and Musical Training: Standing Apart (1792–1802)

In Vienna, Beethoven studied under Haydn (and later other teachers like Johann Albrechtsberger and Antonio Salieri), but his relationships with mentors were fraught with independence. Beethoven respected Haydn's genius but reportedly resisted fully 'bowing' to Haydn's authority in lessons. He often found Haydn's instruction insufficient and secretly sought additional theory training elsewhere. Albrechtsberger later complained that Beethoven 'had learned nothing' from him, since Beethoven only trusted his own experiential learning. This pattern - absorbing knowledge but refusing to conform unquestioningly to teachers - reflects Beethoven's place on the neurological spectrum. He was not a 'Social Person' student who dutifully absorbed the master's every rule; instead, he questioned and tested everything against his own judgment. As one contemporary recalled, Beethoven 'refused to take for granted the edicts of the classroom; he would believe only what he had himself experienced and tested'. This fiercely critical mindset aligns with the NSM's Individual, who 'doesn't accept authority over them when it is based on hierarchy… and doesn't ‘just follow orders''. Beethoven, though technically Haydn's pupil, was already behaving more like an equal, determined to forge a unique style rather than imitate the past.

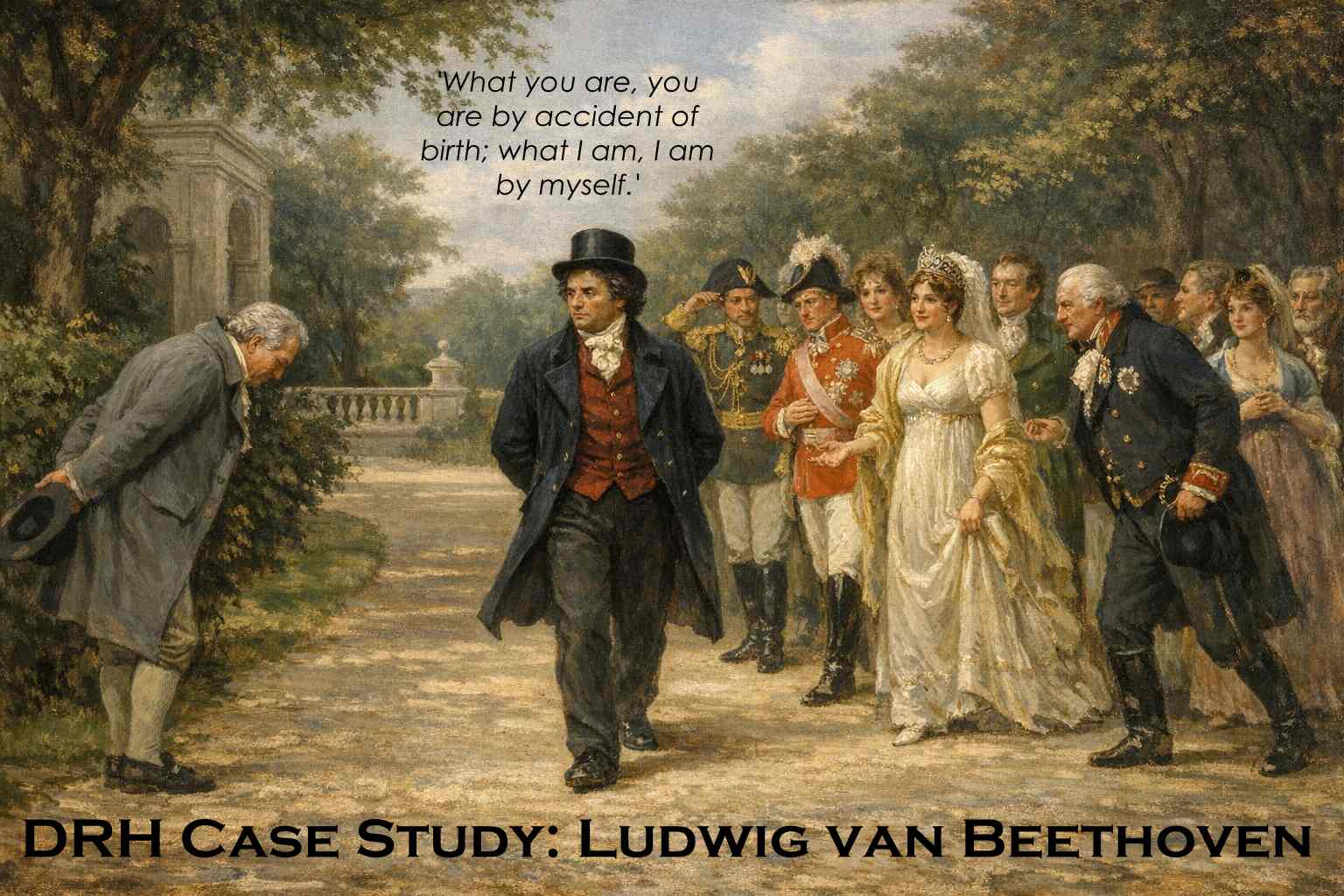

Socially, young Beethoven quickly gained fame in Viennese aristocratic circles as a virtuoso pianist. His improvisations at the keyboard dazzled nobility at salons, and patrons like Prince Karl Lichnowsky and Count Waldstein took him under their wing. However, unlike most composers of the era who depended on aristocratic favour by playing the obedient court servant, Beethoven insisted on his autonomy and dignity. He famously lacked the deferential manners expected of someone of his status (a commoner in a feudal society). One observer noted that Beethoven 'lacked social graces, did not possess any sense of protocol, and refused to follow societal norms such as being subservient to royalty and patrons.' He dressed casually and neglected personal grooming, behaviour the Viennese found eccentric or even boorish. Yet his patrons tolerated these 'annoying' traits and impudence because of Beethoven's extraordinary talent and rising fame. This tolerance underscores a point in DRH: society may ostracise nonconformists, but it also needs them when they produce valued progress. In Beethoven's case, the elite were willing to overlook his lack of conformity in etiquette because he offered something invaluable - musical brilliance that even they had to honour. Beethoven clearly understood his worth. On one occasion in the late 1790s, he is said to have told an aristocrat, 'Prince, you are what you are by accident of birth; I am what I am by myself. There are and will be thousands of princes; there is only one Beethoven.' This bold statement, later echoed in a letter to Prince Lichnowsky in 1806, epitomises Beethoven's self-concept: his individual identity and talent, achieved through personal effort, placed him beyond the normal social hierarchy of rank. Such an attitude was virtually unheard-of among 18th-century musicians. Beethoven was effectively rejecting the collective identity of 'servant' or 'subject' to aristocracy, demanding to be treated as an equal individual. In NSM terms, he viewed society 'horizontally,' where each person is of equal intrinsic value, rather than accepting the 'vertical' class structure of his time. This perspective fuelled many of his confrontations with nobility and set him apart from contemporaries who were far more deferential.

Musically, Beethoven's first decade in Vienna (1792–1802) is often called his 'Early Period'. During these years, he mastered the Classical style inherited from Haydn and Mozart, composing numerous piano sonatas, chamber works, and his first two symphonies. Superficially, Beethoven conformed to professional norms - his early works follow the elegant forms and proportions of the Classical era. But even within these works, listeners noted an intensity and an originality that went beyond the polite conventions of the day. For example, the 'Pathétique' Sonata Op.13 (1798) shocked some with its stormy emotions, and his string quartets Op.18, while Classical in form, carried a vigorous personal stamp. Beethoven was beginning to 'act based on his individual judgment alone,' as NSM's Individual would, rather than simply mimicking his predecessors.

Around 1800, Beethoven faced a personal crisis that would elevate both his individualism and his art to new heights: he began losing his hearing. By his late 20s, Beethoven's encroaching deafness (a deeply stigmatising disability for a musician) threw him into despair. He hid his condition for as long as possible, fearing social ostracism and the loss of his ability to perform. In 1802, while staying in Heiligenstadt, a village outside Vienna, Beethoven wrote an unsent letter to his brothers known as the Heiligenstadt Testament. In it, he confessed that he had 'thought of ending [his] life' due to his suffering, but art and moral duty held him back. 'It seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce,' Beethoven wrote, resolving to overcome his fate for the sake of his artistic mission. This document is telling: Beethoven explicitly frames his struggle in individual terms - his personal calling to create gave him strength to resist suicidal despair. He even implores people to understand that if he withdraws from society, it is not out of misanthropy but necessity due to deafness. In DRH's view, Beethoven's profound isolation here is not pathology but the price of his difference. He is, as he wrote, 'compelled to live in loneliness' by circumstance, and he accepts this burden with almost heroic resolve if it allows him to fulfil his unique purpose. The stage was set for Beethoven to fully transform his style - and arguably the course of Western music - in the ensuing years. He would do so driven by an inner voice and individual vision that took precedence over all outside expectations.

The 'New Path': Beethoven's Heroic Middle Period and Defiance of the Norm (1803–1812)

In October 1802, immediately after the Heiligenstadt Testament, Beethoven reportedly declared to a friend, 'I am not satisfied with my work so far. From today on I shall take a new path.' This 'new path' was no idle remark - it heralded Beethoven's Middle Period, often called his 'Heroic' era, in which he broke decisively with musical conventions. Over the next decade, Beethoven's works became grander, more emotional, and unapologetically original, startling audiences and critics. In the NSM framework, this is Beethoven fully embracing the role of the Individual innovator: he 'began breaking with traditions and rules and defying conventions,' as one analysis notes. He consciously rejected the notion that the status quo in music was ideal or complete. Instead, like a true progressive on the individual end of the spectrum, he 'welcomed progress' and sought to push art into new realms, regardless of conservative backlash.

The watershed work of this period was Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55, known as the Eroica ('Heroic'). Composed in 1803–1804, the Eroica shattered previous notions of what a symphony could be: it was nearly twice as long as typical symphonies, brimming with bold key changes, structural innovations, and a level of emotional depth and narrative scope never before heard in instrumental music. Initial reactions were polarised. Musical connoisseurs were divided into 'several parties,' with some hailing it as 'a masterpiece' and others dismissing it as 'a confused, overly long, and bizarre' composition. One early reviewer complained that the Eroica had 'too many ideas… an endless duration… it exhausts even connoisseurs', and that Beethoven should learn to be more clear and compact. Another critic famously sniffed that the symphony was intelligible only to those 'who worship [Beethoven's] failings and merits with equal fire'. Such critiques illustrate how far Beethoven had deviated from the collective musical taste of 1805. He was, in effect, leaving much of his audience behind in order to pursue what he believed music should express. When confronted with perplexed or hostile reactions, Beethoven did not capitulate or simplify his art. Instead, he remained confident in his vision. To detractors of his adventurous works, he is said to have retorted that they were 'music for a later age.' Indeed, Beethoven foresaw that the collective contemporary public might not immediately appreciate his innovations, but he trusted that posterity would. This remark captures the essence of deindividuation resistance in creativity: Beethoven was willing to be misunderstood and even unpopular in the short term, rather than dilute his originality to appease the crowd. His focus was on the integrity of his individual artistic voice - a trait he shared with other paradigm-breaking figures who, according to the DRH, propel progress while the masses catch up slowly.

The Eroica also had an explicitly political and philosophical dimension that showcases Beethoven's independent ideology. He originally dedicated the symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte, whom Beethoven admired as a liberator embodying Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and the rights of man. In Beethoven's eyes, Napoleon as First Consul was a hero of the people, an individual rising above Old World monarchy. However, when news arrived in 1804 that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor, Beethoven reacted with violent outrage. According to his secretary Ferdinand Ries, upon hearing the news Beethoven 'broke into a rage and exclaimed, ‘So he is no more than a common mortal! Now he will tread under foot all the rights of man… become a tyrant!''. Beethoven then seized the title page of the symphony - which bore the dedication 'Buonaparte' - and 'tore it in half and threw it on the floor,' obliterating Napoleon's name from the score. He ultimately re-titled the work Sinfonia Eroica, ‘composta per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grand'Uomo' - 'composed to celebrate the memory of a great man'. In other words, the idea of the hero remained, but Beethoven refused to honour the flesh-and-blood Napoleon once he betrayed the ideal. This dramatic episode shows Beethoven's moral independence: he did not hesitate to defy his own former hero (and risk offending pro-Napoleonic aristocrats) when that hero's actions violated Beethoven's principles. Beethoven's loyalty was to Enlightenment ideals, not to any group or authority figure. In NSM terms, he 'promoted the moral values he lived by' rather than blindly following the shifting positions of any leader or group. The individual on Beethoven's spectrum stands 'for what is right and just, regardless of affiliation' - precisely what Beethoven did in renouncing Napoleon, even as much of Europe still adored the French leader. This independent political stance also manifested in Beethoven's only opera, Fidelio (premiered 1805, revised by 1814), which is a celebration of personal liberty and defiance of tyranny. Beethoven was drawn to the opera's story of a wife (Leonore) who disguises herself to free her husband from unjust imprisonment by a despotic governor. Notably, Fidelio features a female protagonist who is heroic - something Beethoven insisted on despite it being unconventional in that era. The opera's finale, where political prisoners are liberated, reflects Beethoven's own reverence for freedom and justice over compliance with authority.

Throughout the middle period, Beethoven accumulated more legendary anecdotes of refusing to conform socially. A famous incident occurred in 1806 at the estate of his patron Prince Lichnowsky. Lichnowsky, who adored Beethoven, had invited some French officers (enemy occupiers at the time) and wanted Beethoven to perform for them. Beethoven bluntly refused to play for Napoleon's officers. When the Prince insisted, Beethoven's temper flared - he stormed out of the palace amidst a thunderstorm. Later, Beethoven sent Lichnowsky a letter (or according to some reports, etched the message on the Prince's bust) with the fiery declaration: 'Prince, what you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am of myself. There will be thousands of princes; there is only one Beethoven.' This was essentially a severance of his patron–client relationship. Beethoven would rather shatter a friendship and endure financial uncertainty than be treated as a mere court minstrel at odds with his conscience. His pride in his individual worth and his unwillingness to 'follow orders' from a social superior could not be subdued. In the DRH framework, here is a man 'ostracised and pathologised' (some in Viennese society surely considered Beethoven arrogant or ungrateful) for 'resisting social conditioning' - yet this resistance is what allowed him to create unencumbered by servility.

Another celebrated encounter underscored Beethoven's rejection of collective identity hierarchy. In July 1812, Beethoven met Johann Wolfgang von Goethe - the most revered poet in German lands - at the Bohemian spa town of Teplitz. The two great minds shared admiration but also very different attitudes about social decorum. One day, as Beethoven and Goethe strolled together, they crossed paths with the Empress of Austria and her royal entourage. Goethe, ever the courtly celebrity, immediately moved aside and removed his hat, bowing in respect as the nobles approached. Beethoven, however, would have none of this deferential charade. He urged Goethe, 'Keep hold of my arm… they must make room for us, not we for them.' When Goethe hesitated and stepped aside, Beethoven strode straight through the dignitaries, 'arms folded, hat still on,' barely nodding as 'princes and officials made a lane for him' and even Beethoven's own patron Archduke Rudolph tipped his hat first in greeting. On the other side, Beethoven waited for Goethe and chided him: 'I've waited for you because I honour you, but you did those yonder too much honour.' Beethoven relished recounting how he had 'teased Goethe' by flaunting his disregard for rank. This incident (though reported later by Bettina von Arnim, a friend of both men) perfectly encapsulates Beethoven's social ethos. He truly believed in the 'horizontal' society of equals. To him, geniuses like Goethe and himself were the true 'great men' whom 'kings and princes must honour', not the other way around. 'Kings and princes can create titles and orders, but they cannot create great men… when two such as I and Goethe walk together, these grandees should bow to us,' Beethoven asserted in a letter. Goethe, who enjoyed noble patronage and titles, was embarrassed by Beethoven's brazenness, illustrating the divide between an accommodating Social Person and a bold Individual. Beethoven simply did not internalise the era's class-based identity; he acted 'immune to outside influences' of aristocratic pressure and followed his own principle of human dignity. This story has become emblematic of Beethoven's anti-authoritarian posture - a personality trait very much in line with a Deindividuation Resister who 'stands up for what they believe is right… regardless of their affiliation'.

Musically, Beethoven continued to innovate fearlessly through the 1800s. He introduced unheard-of ideas: for example, incorporating voices into a symphony (his Ninth Symphony of 1824 would be the first major choral symphony) and using a lyrical solo female voice as the hero in an opera (Leonore in Fidelio, as noted) - choices that broke accepted norms. He also expanded forms (his Fifth Symphony built an integrated four-movement narrative, his piano sonatas like the Waldstein and Appassionata pushed the instrument's limits) and tried novel combinations (the Archduke Piano Trio Op.97, the Razumovsky String Quartets Op.59 introducing Russian folk themes per a patron's request but in startling ways, etc). Not every experiment was understood: when his three Razumovsky quartets (1806) bewildered some musicians with their difficulty and odd modulations, one violinist quipped that either Beethoven was crazy or he was making fun of them. Beethoven reportedly retorted, 'They are not for you, but for a later age,' reaffirming his conviction that his individual vision transcended his own time. Many of Beethoven's compositions in this period carry a spirit of heroism, struggle, and triumph over adversity, which musicologists often relate to Beethoven's personal narrative of overcoming deafness and isolation. It is tempting to see Beethoven casting himself as the 'hero' in his music - a Promethean figure who defies the gods (fate, convention) to deliver fire (artistic enlightenment) to humanity. In the NSM/DRH perspective, Beethoven's heroic self-conception is not narcissism, but rather a manifestation of the 'strong sense of individual identity' that enabled him to act as a torchbearer for progress. He viewed his talent as a duty to humanity (in his words, a 'love of mankind and desire to do good' fuelled his work). This aligns with Ludwig's hypothesis that individuals who resist groupthink often have a moral drive to improve the world, unlike those who conform and simply uphold the status quo. Beethoven indeed wrote music not to please a particular class or patron, but to express universal human ideals - freedom, justice, joy, brotherhood - thereby leaving a legacy that elevated the collective in the long run.

By 1812, Beethoven was at the height of fame, but his deafness had also advanced considerably. He could no longer perform as a pianist and relied on notebooks (conversation books) to communicate. The world around him was also changing - the Napoleonic Wars had ended, and reactionary politics were on the rise in post-war Europe. Beethoven's middle period closed with works like the Seventh and Eighth Symphonies (1813–1814). The Seventh, with its wild, 'Dionysian' energy, and the compact Eighth (which humorously thumbed its nose at critics expecting another grandiose work) both show Beethoven doing as he pleased, not what fashion dictated. After 1812, Beethoven's output dropped during a difficult period of health and personal troubles, but this pause was the prelude to an even more radical chapter: his Late Period.

Late Years and Inner World: Isolation vs. Individuality (1813–1827)

Beethoven's late period (roughly 1815 until his death in 1827) was marked by severe personal challenges, increasing seclusion, and the creation of some of the most profound and unconventional music ever written. In these years, Beethoven became almost completely deaf - a composer who could no longer hear the performances of his own work, an irony that alienated him further from society. At the same time, he became embroiled in an all-consuming family conflict: the fight for custody of his nephew Karl. This episode is especially illuminating when viewed through the DRH lens, as it shows both the noble and the dark sides of Beethoven's uncompromising individuality.

In 1815, Beethoven's brother Carl died, leaving behind a young son, Karl, and Carl's wife Johanna. Beethoven was contemptuous of Johanna (he considered her of bad character - 'an immoral mother' - and called her the 'Queen of the Night'). Determined to 'rescue' his nephew from what he saw as a corrupt environment, Beethoven resolved to gain sole guardianship of the boy. Over the next five years, he waged a protracted legal battle against Johanna, exploiting his prestige and even some legal maneuvering (at one point, Beethoven misrepresented the 'van' in his name to claim noble status so the case would be heard in a higher court). Beethoven's 'overriding determination to be in sole control of Karl's destiny' was evident. He truly believed he knew what was best for the child and refused to compromise or share custody. By 1820, he succeeded in winning custody. Once Karl came under Beethoven's roof, Beethoven imposed his own strict regime on the teenager: he chose Karl's schools, forbade almost all contact with Karl's mother (even having the police retrieve Karl when he ran off to see her), and directed Karl's career path. Beethoven initially insisted Karl become a musician, making the boy take piano lessons from Beethoven's student Carl Czerny despite Czerny's report that Karl 'had no musical talent.' Later, when Karl expressed a desire to join the military instead of pursuing academics or music, Beethoven's reaction was explosive; he flew into 'paroxysms of rage.' The relationship deteriorated under Beethoven's overbearing, if well-intentioned, parenting. Karl grew depressed and felt caught between a domineering uncle and an ostracised mother. In summer 1826, the 19-year-old Karl attempted suicide, shooting himself in the head (he survived with a minor wound). It was a shocking crisis. When asked why he tried to end his life, Karl reportedly said, 'Because my uncle tormented me so'. He asked to see his mother upon surviving, which he did. For Beethoven, this was a crushing blow - 'final proof he had failed in his attempt to be father to Karl.' A witness noted that Beethoven 'never truly recovered from the shock' of this tragedy. In the last months of Beethoven's life, Karl entered military service and was absent when Beethoven lay on his deathbed in March 1827.

The Karl saga reveals how Beethoven's resistance to society could sometimes curdle into personal inflexibility. He was fighting what he saw as a moral battle against an 'immoral' parent and against the easy path of letting Karl be ordinary. Beethoven likely projected his own ideals onto Karl - wanting him to be an enlightened, accomplished bearer of the Beethoven name, not a 'normal' youth under a 'frivolous' mother's influence. This reflects the Individual's tendency to hold themselves to high principles rather than follow community norms. However, the outcome - estrangement and misery - suggests the cost of such extreme individualism in personal life. Beethoven's inability to empathise with Karl's own wishes or to yield his obsessive control can be seen as a flaw borne of the same independent streak that made him great. It underscores DRH's point that society often misunderstands and even pathologises those who don't conform. Indeed, one could argue Beethoven's contemporaries might have seen his behaviour as irrational or 'insane' - some of Beethoven's friends were alarmed at his single-mindedness, and later commentators speculated Beethoven had a 'monomaniacal' streak. Yet, from another angle, Beethoven was adhering to a personal moral logic: he earnestly believed he was saving Karl from deindividuation by a corrupt society. In a poignant twist, Beethoven's effort to forge Karl into a brilliant Individual like himself only drove the boy to despair. This tragedy humanises Beethoven, showing that the qualities of a deindividuation resister (unyielding integrity, defiance of outside interference) can be double-edged in private life.

Despite personal turmoil, Beethoven's creative spirit in the late period burned undiminished - if anything, it reached new heights of originality precisely because he was so isolated from public fashions. Between 1818 and 1826, Beethoven composed works that were bewilderingly ahead of their time: the last five piano sonatas (Opp. 101, 106, 109, 110, 111), the Missa Solemnis (his grand sacred mass, Op.123), the monumental Ninth Symphony (Op.125 with its choral 'Ode to Joy'), and the set of Late String Quartets (Opp. 127, 130–133, 135). These compositions are the fullest expression of Beethoven's individuality. They abound in structural innovations, unexpected emotional shifts, and intellectual depth. For example, the late quartets feature extreme contrasts, fugues of unprecedented complexity, and intimate spiritual profundity that left early listeners perplexed. One reviewer in 1825 wrote that Beethoven's latest quartets were 'indecipherable, like the jargon of angels' - implying they transcended normal understanding. Beethoven himself, knowing that even educated listeners struggled with these works, maintained utter confidence in his artistic choices. He famously scribbled in one of his late manuscripts, 'Es muss sein!' ('It must be!') - reflecting his conviction that the work must follow the necessity of his inspiration, not the taste of the crowd. As NSM's Individual archetype, Beethoven in his 50s was entirely 'immune to outside influences' regarding his art. At this stage, he hardly had to consider patron demands (his fame secured him enough support) and he no longer performed publicly, so he focused solely on composing what he felt was true and beautiful.

It is noteworthy that by now Beethoven's relationship with the public was paradoxical: he was revered as the greatest living composer, yet much of his latest music went largely uncomprehended. When the Ninth Symphony premiered in 1824, Beethoven (totally deaf) had to be turned around on stage to see the thunderous applause behind him, as he could not hear it. Even so, critics were divided on this choral symphony with its radical format and exuberant message of universal brotherhood. Some elite thinkers found the inclusion of voices (singing Schiller's An die Freude - ' Ode to Joy') crude or the length outrageous, while others sensed its genius. In the DRH context, one could say Beethoven's individual vision was in the process of being gradually adopted by the collective. By setting Schiller's poem about 'Alle Menschen werden Brüder' ('All men become brothers'), Beethoven made perhaps his most explicit statement of belief: that all humanity should be united in joy and dignity. This was the same egalitarian ideal he had lived by - refusing to accept that some men (princes) were higher than others (commoners). Now he delivered that message in the most grandiose musical proclamation imaginable. Over time, the Ninth Symphony's Ode to Joy has indeed become a near-universal collective anthem (from European Union events to the Olympic Games), vindicating Beethoven's faith that his 'music for a later age' would ultimately be embraced. What was once the idiosyncratic creation of a nearly isolated genius is now part of the shared identity of humanity - a perfect illustration of DRH's idea that the Individual innovator's work is spread by the network of society afterwards.

Beethoven's final years were lonely and beset by illness. He lived in modest apartments around Vienna, increasingly cut off from casual conversation due to deafness. Visitors found him in disarray - his rooms messy, his appearance 'disheveled', hair wild, often talking aloud to himself or absorbed in writing. More than ever, he paid no heed to public opinion of his lifestyle. One famous story from 1824 recounts how Beethoven, while lost in thought on a walk outside Vienna (muttering and waving his arms in conducting motions), was arrested by a local policeman who took him for a vagrant lunatic due to his unkempt look. Beethoven angrily shouted his name to no avail ('I am Beethoven!'). Only after a friend or local magistrate recognised him was he released - the town even gave him new clothes and food in apology. This comical incident underscores how far Beethoven's outward behaviour diverged from societal norms - to the point of being literally pathologised (seen as madness or vagrancy) by an authority. And yet, his condition was the flip side of his genius. Felix Mendelssohn later put it poetically: Beethoven walked a fine line 'between genius and insanity', living on that edge where great art and personal chaos often coexisted. To frame it via NSM: Beethoven had sacrificed nearly every collective comfort - smooth social relations, a stable family life, public acclaim during his lifetime - in order to remain utterly faithful to his individual identity and purpose. In doing so he endured great loneliness ('I live alone, alone,' he had written during the Teplitz summer), yet he also achieved a creative freedom that few have ever attained.

On March 26, 1827, Beethoven died after months of bedridden illness (cirrhosis of the liver and other complications, possibly exacerbated by lead poisoning). He was 56. In a final gesture of independence, he reportedly, as a storm raged outside, shook his fist at the heavens. At his funeral, an estimated 20,000 people lined the streets of Vienna to pay respects. The poet Franz Grillparzer's elegy was read, proclaiming that Beethoven had 'become a power unto himself' and 'whoever comes after him will not be able to follow him'. Ironically, the city that had often misunderstood or mocked Beethoven's eccentricities now honoured him like a hero. In death, Beethoven's individualistic life was recognised as a model of artistic virtue. As Grillparzer noted, Beethoven had 'shaken the clods from his feet' (a reference to Beethoven's peasant origins and perhaps his refusal to be held down by society) and 'stood firm among the gods.' In other words, the one Beethoven - that unique self Beethoven always insisted on - had transcended the 'thousands of princes' and earned a secular immortality.

Legacy and Conclusion: Beethoven as Deindividuation Resister

Today, Ludwig van Beethoven is lionised not just for his musical masterpieces but also as a cultural symbol of the rugged individual in art - the artist who suffers, resists, and revolutionises. Through the analytical lens of the Neurological Spectrum Model and the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis, Beethoven's biography shines as a prime example of how an Individual-oriented disposition can drive historic innovation. He consistently resisted deindividuation, from his boyhood refusal to be a docile child-prodigy, to breaking free of patronage expectations as a young man, to reinventing the language of music in his 'new path,' to thumbing his nose at emperors and conventions alike. He retained what DRH would call his 'individual identity despite the repercussions' - indeed, he faced ridicule, social friction, and personal hardship as a result. Far from being a social chameleon, Beethoven was closer to what some might term 'neurodivergent' today: socially awkward, hyper-focused, intolerant of trivialities, possibly prone to mood swings, and unyielding on matters of principle. However, rather than pathologise Beethoven, the NSM/DRH framework suggests we view these very traits as the engines of his contribution. Beethoven illustrates Frank L Ludwig's assertion that 'progress is driven by those who resist social conditioning … while those who identify collectively provide the network to spread it.' In Beethoven's case, his radical musical ideas were at first carried by a small network of enlightened listeners and performers (his mainstream allies, one could say), and over decades the wider musical world (the 'collective') caught up, propagating and normalising what was once extreme. For example, the harmonic boldness that shocked in the Eroica became the new symphonic standard by the late 19th century; the personal, expressive style Beethoven pioneered became the bedrock of Romantic music, inspiring composers like Schubert, Brahms, Wagner, and many others who explicitly built on Beethoven's legacy. In that sense, Beethoven catalysed a shift in the collective artistic identity - a testament to how an outsider's vision can eventually become mainstream.

Psychologically, Beethoven exhibited many traits of what DRH calls a 'deindividuation resister': he was original, nonconformist, morally independent, defiant of unjust authority, and creative. He had an intrinsic sense of equality (recall how he treated nobles and commoners alike, demanding the same respect in return) and a strong conscience (his decisions like renouncing Napoleon or fighting for his nephew were driven by his own moral compass, however arguable the outcomes). He also took responsibility for his actions - another Individual trait - whether it was apologising in the Heiligenstadt Testament for his irascibility (blaming his deafness but still expressing remorse to those he might have hurt) or acknowledging that his stringent approach to Karl might have failed. In contrast, a 'Social Person' might have blamed others or fate. Beethoven's letters and conversation books show a man who could be brusque and proud, but also deeply concerned with virtue, reputation (in the sense of posterity's judgment), and genuine fraternity with those he loved. He loathed insincerity and refused to flatter or lie to curry favour - aligning with the NSM description that 'The Individual says what they mean and know to be true,' whereas a Social Person would say what is expected. Beethoven's blunt honesty often got him in trouble socially, but it also earned him life-long loyal friends who cherished his authenticity and goodness beneath the rough exterior (friends like Stephan von Breuning, the Brentano family, his pupil Ferdinand Ries, and Baroness Dorothea Ertmann all spoke of Beethoven's kind heart and generosity in private). This suggests Beethoven was not anti-social by nature - he craved love and friendship - but he simply could not pretend or conform to social niceties that felt false. His later isolation was thus not the result of misanthropy; it was the combined result of an unforgiving disability and his refusal to capitulate to societal expectations of how a composer-genius should behave (meekly entertaining the nobility, etc.).

Modern observers have sometimes speculated that Beethoven might fit the profile of an autistic individual, given his social difficulties, obsessive work habits, and intense focus on his interests. Intriguingly, the Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis explicitly argues that autism (or the behaviours labelled as such) can be understood as a social construct applied to people who resist social conditioning. Beethoven could serve as a supporting example for this thesis: throughout his life people around him attempted to 'normalise' him - to make him behave more politely, to write more conventionally pleasing music, to live as others do - and each time Beethoven pushed back, sometimes at great cost. Rather than label him disordered, the NSM/DRH perspective would celebrate Beethoven as someone who preserved the innate individual identity we are all born with (as Ludwig's abstract says, 'all children are born with individual identities') instead of succumbing to the pressures that make 'two-thirds of all humans' into conformists. In Beethoven's era, there was no concept of neurodiversity or psychological accommodation for eccentric genius; Beethoven carved out his own accommodation by demanding that the world accept him on his terms - and ultimately, it did.

In conclusion, Ludwig van Beethoven's life from cradle to grave can be read as a triumphant, if often painful, narrative of an Individual versus the Collective. He consistently acted according to his personal vision and values, embodying what he himself called 'frei sein' – to be free. His music and biography together argue that true artistic greatness requires resisting the pull of the crowd - the 'world's rubbish,' as he referred to trivial societal matters - and tuning one's actions to a higher ideal. Beethoven's alignment with the Individual end of the neurological spectrum gave him the courage to, in his words, 'seize Fate by the throat' and not let it bend him. The very traits that made him an awkward man made him a revolutionary composer. As a result, Beethoven left a legacy that transformed his art form and inspired social movements (his music became associated with freedom and hope worldwide). His Ninth Symphony's choral finale, invoking unity and the worth of every individual, stands as a cultural monument to the principles Beethoven championed by example. In Beethoven, we see the quintessential Deindividuation Resister: not a perfect being by any means, but one who, through steadfast individuality, altered the course of human creative progress.

Sources:

• Beethoven's personal letters and reported conversations (e.g. Heiligenstadt Testament, correspondence with Bettina von Arnim)

• Contemporary accounts of Beethoven's life by friends and biographers (e.g. Czerny, Ries, Schindler) compiled in secondary sources

• The Neurological Spectrum – Between Individual and Collective Identity (Frank L Ludwig)

• How Humans Progress: The Deindividuation Resister Hypothesis (Frank L Ludwig)

• Classic FM and other music history resources for biographical anecdotes

• Wikipedia and scholarly analyses for historical context (e.g. Eroica Symphony development and reception)